25 Greatest Documentaries of All time: Part 2

Arlin is an all-around film person in Oakland, CA. He…

There is a common misconception that documentaries are somehow easier than traditional narrative film making, that all it constitutes is finding something interesting and pointing your camera in that direction. But that is precisely because that is how they are intended to appear. A great documentary is like a great matte painting in a Hollywood feature; it looks completely real and thus its artifice is practically invisible, but it was actually created with extraordinary craft and is the result of a series of artistic choices. The most successful documentaries are the same way; they seemingly present reality when in fact they are wholly artistic constructions.

In the previous installment of this piece, which can be found here, I counted down the first thirteen of what I believe to be the twenty-five greatest non-fiction cinematic mattes. Those films gave us personal stories as well as looks at national history, and took us from the halls of Harlem to your own backyard. The next twelve will continue this eclectic theme and range from from the amusing to the soul-penetrating.

I mentioned in my previous introduction that I was going to try to eschew the established documentary canon somewhat and present my subjective take on cinema’s greatest documentaries. As I count down the remaining twelve, there are some realities that are inescapable; documentaries that have been canonized for a reason, namely, that they’re damn fine films. That being said, I am confident that the following twelve documentaries truly are the greatest ever made, and I would be honored if you would allow me to share them with you

12. Hands On a Hard Body (1997)

Directed by S.R. Binder

Hands On A Hard Body is like a Seven Samurai of misplaced hope; the old geezer, the seasoned veteran, the young buck, the girl, the token black guy etc. are all brought together not to defend a poor farming village, but for the opportunity to win a brand new pick-up truck. The catch? In order to win, they must stand upright with at least one hand on said truck longer than any of the other participants, with no time limit. Allowed only a five minute break every hour, and a 15-minute one every six, the contest quickly turns from an exercise of physical stamina to one of sheer will.

The film is a showcase of humanity; from anxiety and jubilation, to loss and pain, the full emotional spectrum is on display through the course Hands on a Hard Body. Everyone has their own regimen and secrets that they believe will give them the edge against the others. As the contest shifts from hours to days, delirium and exhaustion start to set in. Contestants begin to drop for momentary lapses of judgement, taken out by a casual gesture or declaration of faith.

But such is life, as so often something to which we give no thought ends up having drastic consequences. Hands On a Hard Body thus depicts an alternate, perhaps more honest, perspective on the American dream: that one can move up in this world of ours, but doing so has far less to do with merit than it does absurd circumstance.

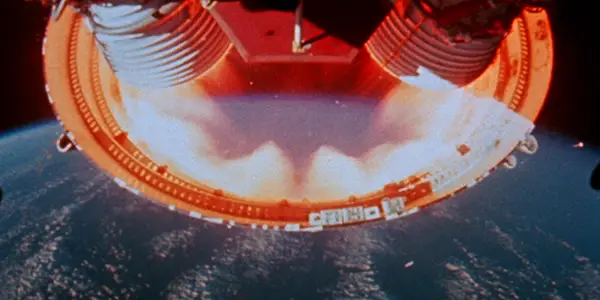

11. For All Mankind (1989)

Directed by Al Reinert

I can think of few films, fiction or otherwise, with as much sheer majesty as For All Mankind. Compiled using footage and audio taken by the Apollo mission astronauts while in space, the film humanizes both the seemingly grand and incomprehensible experience of traveling from the earth to the moon, as well as those charged with the task. The viewer is often presented with details of the daily minutiae of this gargantuan voyage, such as the astronauts’ hygiene regimens, and offered a singular kind of perspective only gained by seeing the whole world in its entirety at once.

One of the film’s most affecting scenes is owned by Michael Collins, the third Apollo 11 astronaut whom you probably never heard about. While Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were on their historic moonwalk, someone had to be back in the ship making sure that they had a means of returning home, and that someone was Collins. His ruminations on the nature of his unprecedented situation and the uncertainty of his friends’ fate on the floating rock below are representative of the unique perspective shared with us by these astronauts.

Everyone on Earth has their own idea of what it would be like to be in space, but to hear it from these men as it was happening, and to see exactly what they were seeing, is a truly transcendent cinematic experience that has never even come close to being touched by special effects or CGI. Thus, for most of us (at least right now), a viewing of For All Mankind is likely the closest we’ll ever get to experience space travel.

10. Grey Gardens (1975)

Directed by Albert & David Maysles

What can I say about Grey Gardens that hasn’t been said already? It’s a classic, a triumph of individual freedom as well as documentary filmmaking. The film, which has broken free of the niche community of the documentary and into culture at large, profiles “Little” Edie Beale and her mother Edith, cousin and aunt to Jacqueline Kennedy, respectively. Their co-depedent relationship anchored to the dilapidated mansion which they have called home for decades, the film merely observes them as they go about their day, pontificating on regrets, former loves and life philosophies, all while feeding their countless number of cats.

One thing that always interests me when I watch the Grey Gardens is how the directors, the Maysles, become characters in their own film. Little Edie is undoubtedly the star, and spends a good portion of the film monologuing to the camera, addressing Albert and David by name. She engages in acts clearly staged for the benefit of her house guests, most famously in a dance number involving a small American flag.Yet, documentary is not only capable of capturing reality but also the psyche. What differentiates an act staged for the camera and one caught by it with regards to reality? Are they not both objectively happening in the world?

The only thing that separates the two is our evolving perception of authenticity, that an act done for the camera’s benefit is inherently less credible. But there is something about the way that Little Edie interacts with the Maysles‘ lens that is as legitimate in its revealing of her character as a more traditional “fly on the wall” approach might. Thus, the setting of the film is as much Little Edie Beale’s inner world as it is the eponymous mansion.

Aside from the film’s well-known offspring, a Hollywood adaptation and Broadway musical (its Bealesmania!), the Maysles released The Beales of Grey Gardens in 2006, a sort-of-sequel, comprised of deleted scenes and unused footage from their original visit to Grey Gardens. That film treats the viewer to the same feelings of engrossing concern inspired by the original pretty much right away, and will no doubt satisfy the expectations of any Beale’s junkie.

9. Burden of Dreams (1982)

Directed by Les Blank

There are a few notable docs on grand but troubled exercises in filmmaking of various degrees of success, prominent among them are Hearts of Darkness and Lost in La Mancha, but only Burden of Dreams has the benefit of having human poem Werner Herzog as its subject. Chronicling the production of Herzog‘s film Fitzcarraldo, Burden is unique because of Herzog’s career long fascination with blending documentary and fiction; he insists there be actualities depicted in his scripted films (as well as some staged moments in his documentaries), thus making Blank‘s film a doc on a doc of sorts.

Though generally about the shooting in Peru as a whole, the film’s main focus is on the logistics of one scene in particular; the pulling over a large hill of a full-sized steamship at a relatively steep grade. To achieve this, Herzog enlists the help of the local Machiguenga tribe to power the ship’s monstrous ascent. Caught between the natives, the sweltering heat, his disillusioned crew and the oppressive untamed jungle, Herzog throughout the film appears to tread the line between being totally in control and completely losing it.

From balancing that line, Herzog ruminates on his shoot from a place of a calm, yet precarious, fervor and with a perspective gained only through both extreme hardship and devotion. Interestingly then, the central metaphor of Blank‘s film becomes the same as that of Herzog‘s entire body of work: the futility of the struggle of humanity in the face of nature. Those interested in an even more detailed account of the making of Fitzcarraldo are encouraged to check out Herzog‘s book “Conquest of the Useless”.

8. Baraka / Samsara (1992 / 2011)

Directed by Ron Fricke

Baraka and its follow-up, Samsara, are two of the densest films on either side of the fiction/non-fiction divide. Masterclasses in the use of traditional Eisensteinian Montage, the films operate on a global scale to imply meaning through the juxtaposition of disparate peoples and landscapes, entirely without the aid of dialogue. Both films are stunning technical achievements, filmed over years and spanning continents, with the latter being shot on 70mm.

Baraka opens with a family of Japanese snow monkeys sitting in a hot spring, seemingly content and in possession of all the ancient wisdom this planet has to offer. It then maps out a survey of the world’s religions; humanity’s attempt to achieve the state of the Snow Monkey. But, as we all know, man has turned further and further from his hot-spring dwelling brethren, and as a result has put both him and them in a precarious situation.

Whereas Baraka acts as a call for self-examination and a reorganization of priorities, Samsara feels much more urgent, portraying a world that has yet to take the messages of the first film to heart. The film’s opening differs starkly from Baraka’s, immediately introducing viewers to a jarring yet entrancing trio of wide-eyed Balinese dancers. Nature here has been lost, skipped over, and in its place lies something full of both confusion and momentum. From this point, Samsara is a last-gasp pleading in defense of the values espoused in Baraka, depicting the absurdity and misdirection of the modern world.

But unlike many message-driven documentaries, these films never feel pushy or beat you over the head with their ideals; rather they are there for you to suss out and piece together for yourself. Though these films are non-linear and absent of diegetic sound, they are not non-narrative, the story just finds its final form in the mind of the viewer rather than on the screen. Thus, Fricke’s films represent some of the most effective and affecting that the documentary has ever know.

7. Crumb (1994)

Directed by Terry Zwigoff

A casual encounter with the work of Robert Crumb could possibly lead one to believe that the author was certainly the black sheep of his family; his work is often lewd, scandalous, hallucinatory, vulgar, violent and racially dubious. However, as pre-Ghost World Terry Zwigoff‘s film Crumb illustrates, Crumb emerged from his 50s Philadelphia upbringing the most well adjusted of the Crumb boys (sisters Carol and Sandra refused to participate in the film). Accompanying him along his return to Philadelphia, and back through his wandering of San Francisco and into his Bay Area home, Crumb is a thorough and honest portrait of one of the world’s greatest, and most controversial, living artists.

The entire spectrum of human existence, vibrant, happy, dark, sinister, hum-drum, illogical, insane, sincere and heartfelt, is all worthy of depiction in the work of Crumb. Known most famously for his work done during the late-sixties, Crumb helped to create what came to be known as “underground comics” or “comix”, for those into the whole brevity thing. The film traces Crumb’s career arc, and gets varying perspectives on his work from a few different colleagues and critics, but the meat of the film is in profiling Robert in his all his glory, from his most cynical to his most hopeful.

The scenes in which he interviews his brothers Charles and Maxon are a treat, in that they offer another layer of understanding to the enigma of Crumb as well as candid, personal moments between brothers that most of us don’t get to witness outside of our own families.

Through his personal friendship with his subject, normally taboo in documentary filmmaking circles, Zwigoff was granted full access to and honesty from the notoriously isolated and curmudgeonly Crumb, allowing him to capture Crumb at his most vulnerable and real: listening to 78s alone in his room, sketching crushes from his high school years, or spending time with his daughter. Even if you have no interest in comic books, art or even the work of R. Crumb, Crumb is required viewing because unlike so many biopics or biographical documentaries you leave feeling like you really have gained a sense of the true nature of that giant person on the screen.

6. The Up Series (1964-2012)

Directed by Michael Apted, Paul Almond

Documentaries usually live in the present, offering a glimpse at a fleeting moment; even if they look to the future, the fact that they must end severely limits their ability to capture the changing nature of people over the course of their lives. The Up! Series bears none of these constraints, and installments concurrently exist within all tenses of time. With the first installment, Seven Up!, airing on British television in 1964, The Up Series is easily the longest documentary production of all time. Taking its titles from the age of its subjects, starting at seven and checking in every seven years thereafter, the series has been an invaluable and committed look at society and class in Britain and human nature more broadly.

The films get longer as their subjects age, incorporating interviews from the prior installments as a reminder of selves both past and unaffected by experience. The first entry, the only one directed by Paul Almond before Michael Apted took the reins, provides the backbone of the series as a fixed point of reference with which the viewer is able to compare the mature adult they see before them.

Seven Up!, aside from being hilarious and adorable, is also illustrative in the extent to which children merely espouse the opinions they hear from their parents, even if they have little understanding as to their meanings. One subject, for instance, Jackie Bassett, has had one racially ignorant comment made as a seven-year old, clearly in echo of her parents’ opinions, follow her somewhat unfairly through her whole life because of her participation in the series. The series then is a document both of how we move away from that place of emotional and psychological dependence and towards ourselves, all while never abandoning or being able to shake that core something about us.

5. Titicut Follies (1967)

Directed by Frederick Wiseman

A horrifying look into a world most of us are lucky to have never had cause to experience, Titicut Follies goes inside the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Bridgewater, a prison for the criminally insane. If that sounds like a place you’d rather not go, that’s probably doubly true of it in 1967. The men inside range from the quirky to the downright scary, and most shades in between. That includes the guards, who are certainly not helpful at best and psychologically abusive at worst. The film takes its name from a talent show put on my the inmates, to which the film periodically cuts, and more plainly, though less painfully, illustrates the absurdity of the institution.

His first film, Titicut Follies is an early aberration of sorts in Wiseman‘s career; most of the films that would follow deal with the more mundane institutions of day to day life, such as the High School, the Zoo or the Department Store. His films feel like they’re shot with an eye rather than a camera, placing the viewer in a kind of John-Cusack-at-the-end-of-Being-John-Malkovic–type state; subjected to the perspective of another person as he explores the settings and scenes around him. This is obviously the case with all films, but Wiseman is honest about it, highlighting rather than eliding that fact.

He goes into these institutions as an alien might, merely observing events as they happen, trying to suss out their inner workings and withholding judgement and meaning until getting in the editing room. This is why his films are often referred to as examples of “Direct Cinema”, also known as the “fly on the wall” approach, a term which he vehemently rejects because of the countless artistic choices he makes in turning hours of footage into a 90 minute documentary (if you have to categorize Wiseman, you could call his films “observational cinema”).

Some institutions are inherently more interesting than others, but Wiseman does them all with the same sense of justice and respect in representation, giving us films he sees as representing the core nature of the institution at hand. Titicut Follies established this rule, and it depicts some things horrific and unsettling (the film was outright banned in Massachusetts for many years), but as with all of Wiseman‘s films it shows that institutions are not static, monolithic beings, but are created by people and constructed to satisfy their whims, and that as such they can be changed to be whatever people wish them. The inmates of Bridgewater unfortunately do not have that ability, but through this film they were at least given a voice that eventually led to the institution’s demise; as strong an effect as a documentary can have.

4. Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997)

Directed by Werner Herzog

Throughout cinema, it has largely been an unwritten rule that documentary filmmakers don’t make great directors of fiction films , and vice versa (though that has never stopped both sets from trying). Since the beginning of his career, Werner Herzog has consistently been the exception that proves the rule. He has achieved this not from stealing the powers of various directors and storing them in a glowing basketball, but by coming to understand that the line between truth and fiction is razor-thin, if it exists at all. Whether sending his actors on a rickety raft down a Peruvian river, or actually planting actresses in a supposedly non-fiction film, Herzog is constantly playing with audiences’ expectations of authenticity and fakery. Little Dieter Needs to Fly is no exception, and uses its director’s signature ambiguity to soaring effect.

The film centers on Dieter Dengler, a German ex-pat who, having dreamed of becoming a pilot since seeing them fly overheard in his youth during WWII, became a pilot for the US Air Force during the Vietnam war. During that time he was shot down and taken hostage in a Vietnamese POW camp. Through his own cunning and planning Dieter was able not only to escape the camp, but make his way through the dense jungle and find his way to rescue. These are facts that form the skeleton around which the film’s narrative will be woven.

We first meet Dieter at his home in California, and instantly we are treated to a falsehood regarding the meaning to him of doors and freedom; Herzog famously collaborated with his subject to fabricate that little tidbit. But we do not remain here long, as the bulk of the film takes place in Vietnam, where Dieter recounts the tale of his capture and subsequent escape in the exact locations in which they occurred. In a technique that would be adopted and adapted 15 years later by Joshua Oppenheimer, Herzog and Dengler are aided in the effort by some Vietnamese, playing the role of the Vietcong captors.

In telling the story while staging a live reproduction, Herzog and Dengler not only obfuscate the line between documentary and fiction, but that between fantasy and reality as well; evident in one scene when Dengler remarks in his German way “This is getting a little too close to home now”. Clearly, re-enacting past traumas might not be the best idea for a former POW, but for the most part little Dieter takes it in stride, seeing the recreation of his arduous journey through until the end.

Herzog would later go on to adapt this story as a live-action narrative feature starring Christian Bale, but that film is an exercise in redundancy; ironically, the adaptation of Dieter Dengler’s story was already achieved at the highest level in the documentary. I personally find no reason to not believe the story as told, but the only one who will ever know the depths of what happened in that jungle is Dengler himself. Given the circumstances, being 30 years after the fact with no access to any of the other original players, Little Dieter Needs to Fly is the best and most truthful way possible to depict the tale.

3. Koyaanisqatsi (1982)

Directed by Godfrey Reggio

Opening with the repeated, droning singing of the film’s title, Koyaanisqatsi is quick to announce that it is not the typical documentary. A Man With a Movie Camera for modern times, first-time director Godfrey Reggio no doubt owes a sizable debt to Vertov‘s seminal film. The film travels across North America, initially depicting the splendor of unspoiled nature, followed by man’s destruction and replacement of it with his own peculiar wilderness: that of the modern city dominated by technology.

With cinematography by Baraka director Ron Fricke and a hypnotic score by the one and only Philip Glass, Koyaanisqatsi represents the complete reciprocal symbiosis between audio and visual that can make a perfect movie; unlike the way most films are done, Reggio gave Glass a very rough cut, then went back and edited it to match the resulting music.

Though similar in structure and execution to Baraka, the reason this film is sitting at #3 and that film is five spots back is because it takes the ethnographic eye that Baraka used to examine the world’s cultures and religions, and turns it on itself, towards the society from which it was sprung. Ethnographic films, now largely out of favor with documentarians, generally operate by othering a subject or culture in such a way that it allows for comparison, usually derisive, with that of the audience. We have a tendency in the West to see progress as inevitable, and our current state to be the pinnacle of achievement, at least until tomorrow. Through the subversion of the traditional ethnographic perspective, the viewer can look at her modern culture in a more honest way; absurd, constructed, unstable and dehumanizing.

Though the film features a lot of mechanical motion as well as natural settings, some of the most affecting shots in the film are moving portraits. Slow motion takes of passers-by catching the lens (or perhaps more appropriately here the original Russian term “kino-glaz”, meaning “camera eye”) make these daily instances of accidental eye-contact something more akin to a confrontationally inquisitive stare-down, highlighting the isolation inherent in modern urban society. Koyaanisqatsi is not concerned with offering solutions or even hope, rather it’s lamenting the rise of an age from which there is no turning back, and the inevitable state of catastrophe that seems equally not so far today as it did in the cold-war 80s.

2. American Movie (1999)

Directed by Chris Smith

American Movie is kind of like Les Blank‘s Burden of Dreams, but on a much smaller scale. It follows Milwaukee-based amateur auteur Mark Borchardt as he and constant companion Mike Schank attempt to complete Borchardt’s horror opus Northwestern (which quickly shifts to a longer-gestating but smaller budget project, Cöven). American Movie beautifully captures the meaning of the title of Burden of Dreams: Borchardt seemingly has no choice as to whether or not he will complete his film, it is simply something that compels him onward ad from which he cannot run away.

I can hear the voices out there in internet land questioning my reasoning here, saying “how can he think American Movie is better than [insert favorite doc here].” Well, it just is. First of all, it’s the greatest comedy of the 90s, hands-down. Docu-coms like The Office and the films of Christopher Guest would kill for writing as good as the unscripted cutaways in American Movie, and I would argue it’s the single most quotable documentary ever made. Mike, through his approachable yet deadpan delivery, owns the best lines and is a constant source of bemusement. The laughs are consistent throughout the film, but American Movie is much deeper than the surface hilarity. It speaks to an experience common to all of those who have ever had creative aspirations: “am I going to pursue my dreams with everything I have, or am I going to acquiesce and join the square working world”.

This dichotomy is represented brilliantly in the film’s opening scene, which shows Borchardt in his home-office, surrounded by books on film and film-making while going through a stack of overdue bills. Throughout the film Mark straddles with and pontificates upon the line between creativity and obligation, but there is no denying his passion for filmmaking. The fervor and dedication with which Mark embarks on his endeavor are so infectious that he ensnares all those around him, from friends and family to the community at large.

He extends his role as Director of Photography to his family across generations when he has to act in front of the camera, and finds a great comedic foil of an Executive Producer in his uncle Bill Borchardt. If Mark is the head of the film and Mike is the heart, Bill is American Movie’s soul. Clearly in his twilight years, Bill’s love and concern for his nephew are palpable if not explicitly stated, his participation was central to the completion of Mark’s dream, and his fatalism a sobering counterweight to Mark’s enthusiastic vision.

This film will hit close to home for aspiring filmmakers, acting as much as a cautionary tale as one of inspiration, but the passion depicted in American Movie will speak to all, and might even reignite that creative spark within you.

1. Hoop Dreams (1994)

Directed by Steve James

It’s Hoop Dreams, it was always Hoop Dreams. It will always be Hoop Dreams. Hoop dreams is Life, Hoop Dreams is Death. Hoop Dreams is hope and Hoop Dreams is fear. Hoop Dreams is family and Hoop Dreams is society. Hoop Dreams. Is. Everything.

Initially intended as a short for public television, Hoop Dreams follows two young basketball prodigies from Chicago, William Gates and Arthur Agee, as they are plucked from the inner-city and recruited by prestigious suburban high school St. Josephs, following the same path as NBA superstar Isaiah Thomas. However, almost nothing winds up as initially envisioned, as institutions, family and fate send the boys on detours the filmmakers could never have predicted.

Filmed over a period of 5 years, Hoop Dreams is not only the best documentary ever made, but I’d argue the best film of all time. It’s the documentary equivalent of a Citizen Kane or 2001; it’s so dense and richly layered and has so much more to offer with each and every repeat viewing. It is also a monumental feat of filmmaking. The filmmakers, director Steve James, cinematographer Peter Gilbert and editor Frederick Marx, were given so much access by the Gates and Agee families and the schools the boys attended that, when shooting was over, they had over 300 hours of footage, which was eventually culled into the nearly 3-hour masterpiece we now know as Hoop Dreams.

The film’s relevance is universal and its applications many, so it is hard to talk about one central theme or meaning with regards to Hoop Dreams; pretty much any school of film or social theory could be applied to it with great rewards. One interpretation I am particularly fond of is the Marxist/Foucauldian approach, which is centrally concerned with the hegemonic structures in society. The film shows how institutions of power, here schools, the NBA, advertisers etc., assimilate raw and emerging talent, Arthur and William, for their own purposes, until that talent is codified within its systems of oppression and the cycle begins anew.

A far less heady approach could concern itself with how the film depicts the few avenues available to the urban poor, and the high instance of folly, exploitation and sacrifice inherent in this particular path of striving for a career in professional basketball. But probably the best way to approach Hoop Dreams, at least the first time, is to just sit back and take in its captivating story, full of enough heartache, twists and joy to rival any Hollywood production (Coach Gene Pingatore of St. Joes ranks right up there with Nurse Ratched and Frank Booth for me).

I could probably go on writing about Hoop Dreams enough to fill a book, but I’ll just conclude by saying that it transcends the documentary and even the medium of film, and now exists in the realm of history and society at large, only gaining relevance as it ages. For this reason and countless others, Hoop Dreams is, without any doubt, the greatest documentary of all time.

Well, that’s it! I hope you enjoyed the journey as much as I enjoyed putting it together. The subjects of these documentaries have varied wildly in tone, content and setting, but they are all united first and foremost by being great films. Completely independent of their messages or content, every one of these 25 movies can go toe-to-toe with any other in terms of entertainment value with confidence, so I encourage you to see them all.

However, we do not watch documentaries solely for entertainment, but also so that we can enrich and broaden our knowledge of the world outside of our own direct experience. I think that by watching all 25 documentaries on this list, one would not only become well-versed in this marginalized but increasingly important genre of film, but become better educated about the world in which they live, and might even come to a better understanding of humanity on the whole, if not also of themselves.

How did I screw up? Which favorite documentary of yours was relegated to #26 or lower?

(top image: Crumb (1994) – source: Sony Pictures Classics)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Arlin is an all-around film person in Oakland, CA. He received his BA in Film Studies in 2010, is a documentary distributor and filmmaker, and runs Drunken Film Fest Oakland. He rarely dreams, but the most frequent ones are the ones where it's finals and he hasn't been to class all semester. He hopes one day that the world recognizes the many values of the siesta system.