GHOST IN THE SHELL (1995): I Believe In Miracles

Ben is a former student of cognitive science who is…

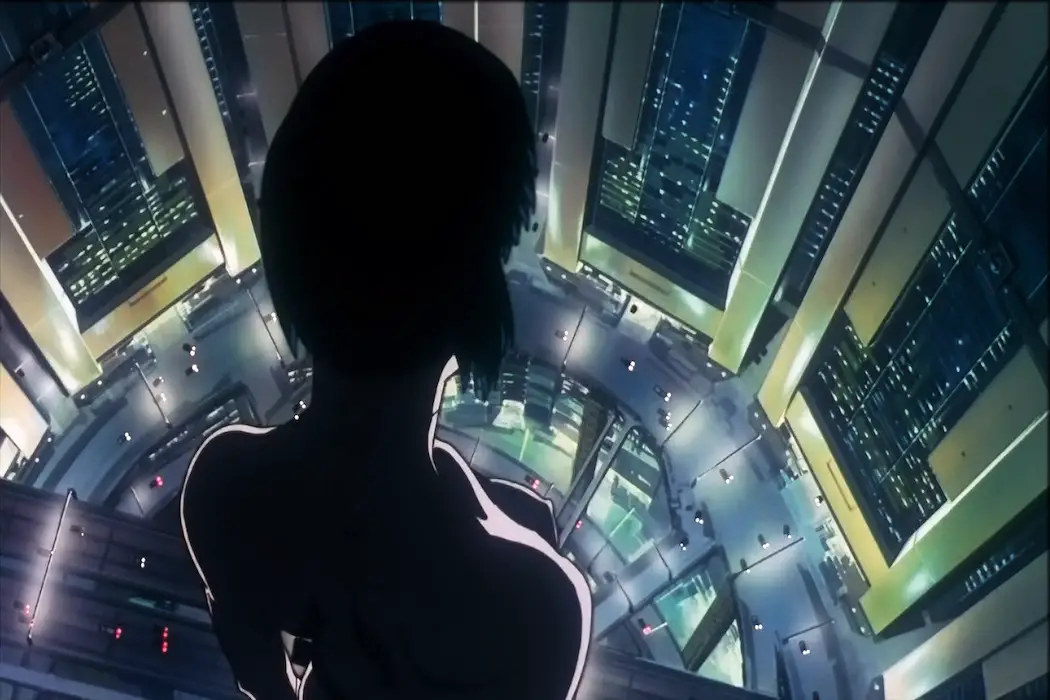

Soon after Ghost in the Shell starts, we see Major Motoko Kusanagi jump out a window after completing a sordid and violent assignment. As she falls in slow-motion, she activates a cloaking device that turns her invisible; her body dissolves, giving way to the sight of the glowing, futuristic cityscape below her. For me, this is one of the weightiest images in the film: a person, augmented by technology, is subsumed by something enormous and convoluted.

It also exemplifies the film’s matchless elegance. From trash floating in the water to mannequins in storefront windows, Ghost in the Shell provides us with signs of life at every turn. At the same time, its images are irresistibly suggestive, offering themselves up to any number of interpretations, encouraged both by the film’s judicious editing and the characters’ attempts to analyze their anxieties.

This is appropriate; Ghost in the Shell is concerned with more than the questions which its characters raise, or which might occur to audience members. It’s concerned with the how and why of philosophy, the way questions arise from the contact between mind and environment. And it’s very important to note that it’s concerned with this as it occurs in practice, observing this phenomenon only as it applies to the relationship between people and technology in a new world connected – or bound – by wires.

Public Security Section 9

Major Motoko Kusanagi, the main character of Ghost in the Shell, works for a security force charged with protecting Japan from cyber-terrorism. She, like the other members of Public Security Section 9, is a former soldier. Right off the bat, it’s clear that the reason Section 9 is staffed by people with military experience is that its work consists, in essence, of military operations.

It’s worth noting, then, that since the Post-War era, Japan’s military has existed expressly for self-defense rather than international conflict (not that it hasn’t participated internationally at all since then). Even so, it’s fairly obvious that Japan still managed to command some international influence in the later decades of the 20th Century, and part of the reason for that was the globally marketable technology produced there.

In Ghost in the Shell, international affairs are inextricably entangled with technology, and the characters – veterans of a third World War that took place before the events of the film – are Japan’s agents on an international stage. Their cybernetic bodies (“shells”) are composed of technological commodities: at one point, the Major sees a stranger whose appearance is identical to hers, presumably because her shell is only one instance of a model that’s freely available on the market.

The instrumentalization of people doesn’t stop at their outward appearances. The story of Ghost in the Shell centers on Section 9’s pursuit of a mysterious criminal known as the Puppet Master, who hacks into people’s minds (“ghosts”). One of the most disturbing concepts in the film is introduced through one of the Puppet Master’s victims: a man whose memories were entirely wiped out.

From this to the Major’s brutal precision and grace in combat, Ghost in the Shell creates a surprisingly prescient vision of a connected world which functions equally well as a speculative character study and a piece of social commentary regarding the international marketplace. The Major’s connection to the world affords her special skills and knowledge; but in some ways, it restricts her, threatening to trivialize her subjectivity by channeling all her actions through assigned roles.

The Banality of Coldness

These circumstances are a source of some anxiety for the Major, which she airs out to Batou, her friend and a fellow agent of Public Security Section 9. In this scene, she launches into one of the film’s handful of long, cold, and heady philosophical monologues. She questions the nature of her consciousness, whether it even means anything to claim an identity in the world of Ghost in the Shell.

But considering the direction in which Ghost in the Shell eventually goes, I’m inclined to think the act of philosophizing itself is more important than the content of these monologues. They allow us to apprehend the way people talk in this setting. This scene is immediately followed by a wordless and digressive sequence that serves only to document the film’s setting. We see an environment that has been almost excessively engineered, crowded with both the varieties of people it’s meant to serve and the disparate methods it employs to that end. Just witnessing the Major in contact with this place does as much for the audience as hearing her monologues.

This scene is accompanied by the signature track on the film’s score (composed by Kenji Kawai): “The Making of a Cyborg”. It’s an austere, ritualistic song with the lyrics of a wedding chant recited in Yamato (an archaic form of the Japanese language). The first time we hear it is during the film’s opening credits, when it plays over a sequence depicting the creation of a cyborg body which may or may not be the Major’s. When we hear it again over an omniscient portrayal of the film’s world, it suggests that the marriage between human and technology goes much further than mechanical prostheses. It pervades the fabric of modern society. It’s almost as basic and second-nature as language.

The trouble is the effect this is having on the Major’s psyche. In a world like this, it’s important to ask whether technology is being used to dominate, deceive, and manipulate. If it is, the Major would be both an agent and a victim, and susceptible to the nihilism of being unable to see herself as anything more than a machine. Maybe the reason Ghost in the Shell comes off as cold to so many people is that the pain it addresses isn’t dramatic so much as devastatingly boring: it insinuates itself into everyday life and slowly suffocates your sense of agency and your belief in the world’s capacity to change for the better.

I’ll Be Your Guardian Angel

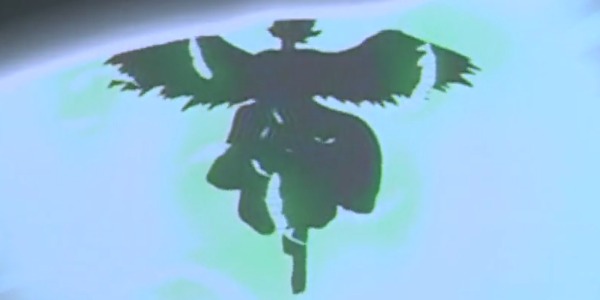

Eventually, there is a resolution to this intractably-networked agony. Ghost in the Shell reaches a turning point, and we begin to receive imagery that challenges assumptions we have as members of a culture and a society that exerts influence through technological connections. Without giving too much away, it reaffirms our subjectivity and rejects all other definition. It resurrects agency by asserting that the only intelligible sense of self is the feeling of difference with the rest of the world, and that that difference means we can affect change through our relations rather than letting them dominate us.

The relief that comes with this is portrayed as a miracle. At the film’s climax, we see an angel descend from the network to the Major. Then, the final scene reinforces the Major’s subjectivity and distinction in the world. It doesn’t forget the modern network’s complexity or the difficulties it presents us with, but now we see it with the added factor of the Major’s newfound resolve and influence.

Ghost in the Shell‘s use of religious imagery is similar to that of director Mamoru Oshii‘s 1985 film Angel’s Egg, which is much more abstract than Ghost in the Shell. That film suggests, almost paradoxically, that a loss of hopeful credulity is needed to truly bring meaning back to a fallen world. In Ghost in the Shell, faith in miracles also arises from a loss in credulity; however, Ghost in the Shell is a much more down-to-earth film than Angel’s Egg, and its notion of credulity far more specific: what it abandons is credulity toward the efficacy and immutability of the modern status quo.

The Net is Vast and Infinite

Of all the European filmmakers Mamoru Oshii has been noted to take influence from, Ghost in the Shell most reminds me of Chris Marker. It draws on the ideas Marker‘s work expressed about technology, film, and the modern world, and applies them ethically. Its ending is open, but not to express ambiguity; it’s open to leave room for action.

The trailers for the upcoming live-action Ghost in the Shell film suggest to me that it’s going to go down a very different path. By no means is it obligated to resemble the 1995 film. Still, it’ll be hard not to sense the shadow the 1995 film casts; it’s just that great.

Does technology play a major role in your life?

Ghost in the Shell is available for home viewing on Blu-ray. It is also available for streaming on Amazon Instant Video and Youtube Movies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JtxWNFfKTok

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Ben is a former student of cognitive science who is currently trying to improve his writing style and ability to understand and appreciate films containing unfamiliar perspectives. He tries not to hold films to a strict set of criteria, but does believe that strong movies can change your outlook on the world. His favorite films include Whisper of the Heart, Hellzapoppin', Foolish Wives, 42nd Street, and the work of Charlie Chaplin.