Staff Inquiry: Our Favorite Actor/Director Collaborations

Arlin is an all-around film person in Oakland, CA. He…

Though film is an inherently collaborative medium, requiring careful cooperation of dozens of individuals, there are two roles that get singled out as being most responsible for the final product. Representing the technical marvels behind the camera and the beauty in front of it, directors and actors are Hollywood’s lifeblood, providing a face for the art that took the efforts of countless unseen.

Sometimes, a director/actor tandem proves so gripping or successful, that a personal and professional bond is forged, and the two continue to work together; sometimes it’s a brief burst, while other times it’s a career-long relationship, but often the familiarity working teams have with one another results in a film of elevated artistic achievement.

Dave Fontana – Alfred Hitchc*ck & Jimmy Stewart

Though Alfred Hitchc*ck and James Stewart reportedly had a tumultuous relationship, due to Hitchc*ck‘s disdain for Stewart‘s method acting style, there is no doubt that their collaboration was a memorable one. Collectively, they created such classics as The Man Who Knew Too Much, Rope, Rear Window, and Vertigo; four films that are often cited amongst the finest in cinematic history.

James Stewart (often called Jimmy by the general audience) is an actor that people most often associate with his “everyman” persona, similar in some ways to how we perceive Tom Hanks today. Due to Hitchc*ck‘s films often touching on ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, such a relatable persona worked alongside his films.

This can be seen most obviously in The Man Who Knew Too Much, in which Stewart‘s character is a doctor that suddenly gets caught up in an international terrorist plot. In Rear Window, though, Stewart plays a traveling photographer, which is a stark contrast to the now forced domestic life he is forced to endure due to his broken leg. Though the two performances are widely celebrated, it is in the remaining Hitchc*ck films that Stewart truly brought his A-game.

Hitchc*ck’s Rope is most celebrated for its unique filming style, in which the entirety of the film is shot in 10-minute segments. Collectively, it tells the story of two highbrow intellectuals who decide to murder someone they consider to be inferior; in addition to this heinous act, they throw a party in the very same room where his corpse is now held.

Stewart‘s character Rupert in the film is easily the most well-rounded of the cast. Though Rupert initially holds some of the same ideals that caused the co-hosts to commit the murder, including the arrogant, pompous manner of the two, he soon realizes the hypocrisy of these beliefs by the conclusion, thereby serving as the most relatable protagonist of the story. Stewart‘s final theatrical speech is also the most emotionally resonant moment of the film. Though the editing style is what is most remembered about Rope, it is due at least in part to Stewart‘s performance that the film still has a lasting impact.

Hitchc*ck and Stewart‘s final film together, Vertigo, is often considered the crowning jewel of their respective careers. Stewart‘s performance as George Bailey in It’s A Wonderful Life might be his most iconic role, but his performance in Vertigo is arguably the most sophisticated of his career.

Playing a retired detective suffering from PTSD, he drastically switches from traumatized to coldly distant to maniacally obsessive throughout the course of the film. Hitchc*ck captured the fierce reality of romantic obsession and madness more strongly in Vertigo than perhaps any movie has before or since, and it is for this reason that it is still his most universally celebrated masterpiece.

Alfred Hitchc*ck and Jimmy Stewart made only four films together in the course of their careers, yet they are amongst the finest in each of their respective filmographies. Hitchc*ck‘s virtuoso style coupled with Stewart‘s practiced method acting made for some truly wonderful and still fondly remembered moments at the movies.

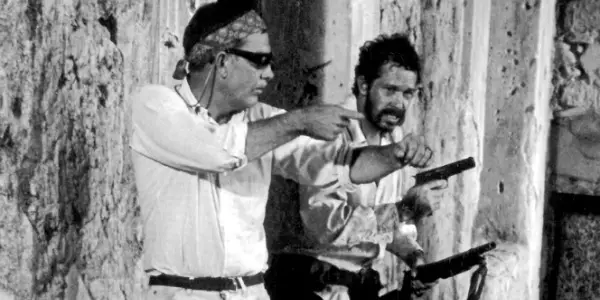

Alex Lines – Sam Peckinpah & Warren Oates

Sam Peckinpah‘s reckless and aggressive behaviour was his best and worst quality. He had an infamous reputation for intense alcoholism that slowly crippled both his body and career, a degenerative disease that made him a huge pain in the ass to be around. The documentary about Peckinpah, Passion & Poetry, showcased a variety of different interviews with many production associates giving horror stories about the notorious director’s callous ways. This volatile personality meant he frequently clashed with those around him, including his closest friends and family, such as one of his frequent collaborators, actor Warren Oates.

Oates is the definition of “the man’s man” in 1970’s American new wave cinema, a man who wasn’t buff or pretty, but ignored what people thought of him, always keeping his cool despite the circumstances. Much like Peckinpah, Oates was also an alcoholic, which lead to his unfortunate early death. The two initially shared a close relationship, with Peckinpah being one of the main reasons Oates made the transition from TV to film (they met on an episode of The Rifleman that Peckinpah directed), but though their similar personalities had them getting along fine in the beginning, their relationship soured as the years went on, until Oates spoke openly about his shattered friendship with the radical director.

Fortunately, it’s noted that the two made up before Oates‘ death in 1982 (Peckinpah died in 1984), leaving a legacy of 4 terrific films together. Whilst his first theatrical film was Private Property (a film which I’ll be reviewing next month as it just received a new transfer), Ride the High Country was the first one that put Oates in prominence, playing one of the antagonists that go after the heroes played by Randolph Scott and Joel McRea. After this, Oates was featured in Major Dundee as part of a huge ensemble cast led by Charlton Heston; it was Peckinpah‘s first troubled production, a trend that would sadly plague the director throughout his career.

The film that’s most worth mentioning when commenting on their collaboration is Peckinpah‘s masterpiece Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, a nihilistic Mexican fever dream that gave Warren Oates his greatest role and fully showcased Peckinpah‘s misanthropic view on humanity. Oates played Bennie, a desperate piano player that goes on a journey to locate the titular Alfredo Garcia to receive a large bounty from El Jefe, a vengeance-seeking cartel leader.

Oates‘ performance is notable, as his interpretation of the character was based on doing an impression of Sam Peckinpah himself, giving Bennie a boozy swagger and an erratic nature that made him lethal but unpredictable at the same time. Bennie’s famous sunglasses were actually Peckinpah’s, which Oates stole off him to complete his brutal caricature of the damaged man.

We can’t end this section without discussing The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah‘s most well-known film, and one which utilizes Oates at his best. Whilst Alfredo Garcia proved that Oates could do terrific work as a leading man, he was more frequently used as a supporting character, solidifying his status as one of the greatest character actors in Hollywood history. The Wild Bunch was made at the peak of both of their careers, with Oates using his silent bad-assness to great effect.

A little add-on is to bring up China 9, Liberty 37, Monte Hellman‘s underrated acid western, which stars Warren Oates as one of the antagonists. Whilst not directed by Peckinpah, he made a rare acting appearance in the film alongside Oates, despite his lack of thespian talent.

Arlin Golden – Federico Fellini & Giulietta Masina

Fellini regularly subjected his leading lady, Giulietta Masina, to all manner of indignities in his films; she’s been insulted for her looks and smarts, bought and sold, abandoned, traumatized, nearly drowned, publicly embarrassed, prostituted, robbed, and cheated upon. In her roles she is constantly giving her love and devotion to men who clearly don’t deserve it.

Like a proto-von Trier, through the suffering and misery of women Fellini revealed the brutal, animalistic tendencies of male nature, and the martyrdom they consequently force upon women. The only difference here is that von Trier‘s relationship with, say Björk or Charlotte Gainsbourg, was never anything other than professional, while when Fellini directed Masina in La Strada, their first cinematic collaboration with him at the helm (Fellini wrote Without Pity in which Masina had a role), they had already been married for over a decade.

Giulietta played muse to Fellini‘s most inspired neorealist films, before he fully embraced the style that came to be described only as “Felliniesque”. In La Strada, she puts on one of the most affecting performances ever committed to celluloid, in a role often compared to those of Charlie Chaplin, but which I’d argue surpasses him.

They then made the little-seen (as in I haven’t seen) Il Bidone, before making Nights of Cabiria, the original film about a hooker with a heart of gold, for which Masina won Best Actress at Cannes. She also starred in Fellini‘s first color film, Juliet of the Spirits, as well as the late-period work Ginger & Fred, in which she paired with Fellini‘s masculine muse, Marcello Mastroianni.

Though he really put his poor wife through the ringer in terms of both her roles and her treatment on set (according to assistant Dominique Delouche, Fellini would be particularly demanding of Masina to avoid the appearance of preferential treatment), the great love he must have felt for her is just as palpable. In all of her roles, Masina has a beaming smile and euphoric energy, both of which are put on full display by her husband’s insatiable desire to watch her dance.

In every one of these films Fellini has his wife snapping and doing her signature high kicks, presented in a way that appears to mix a lack of self-awareness with total self-confidence. In a Roman Catholic way, I believe that these films are actually penance for the director, exaggerating his inadequacies as a husband while painting his wife as a saintly figure, fated to spend her days with men too selfish to ever fully appreciate her.

Jay Ledbetter: Paul Thomas Anderson & Philip Seymour Hoffman

The too-soon death of Philip Seymour Hoffman was the most devastating celebrity loss I have ever had. The man was an absolute genius who surrounded himself with geniuses, including Paul Thomas Anderson. The two three-named geniuses were together since Anderson’s first film, 1996’s Hard Eight, and through 2012’s The Master, collaborating on five films in total. The two were so close that Anderson actually delivered a eulogy at the late actor’s funeral.

Hoffman was generally a small piece of a larger ensemble, but he always managed to take a disproportionate deal of the spotlight in films like Boogie Nights, Magnolia, and Punch Drunk Love. There was a genuine love between the two men that extended far beyond the camera. Yes, it hurt me when Hoffman died, but it cannot even compare to the level of sadness felt by my favorite filmmaker of this, and maybe any, generation.

Hoffman was a Swiss army knife whose various tools were perfectly utilized by Anderson. In Anderson’s films, Hoffman played an insecure homosexual in the world of 1970’s pornography, a sympathetic nurse at the foot of a dying man’s bed, an arrogant mattress salesman, and a powerful manipulator. The man’s range was incredible. He was Daniel Day-Lewis without the bizarre method acting tendencies.

Hoffman had several more unbelievable turns in Paul Thomas Anderson’s films left in the tank, but, sadly, they will never come to fruition. I imagine the burden of genius is great, and the evidence of innumerable untimely deaths of enormously talented people seems to back this up.

Anderson will undoubtedly continue to churn out phenomenal films, but it will be hard for me to think that it wouldn’t be a little bit better if Hoffman was still alive and able to play a role. Two men that talented were made to work together for years and years. Unfortunately for us all, it ended up just being years. We all need to appreciate them.

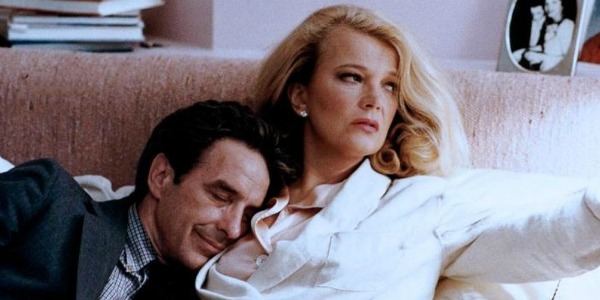

Tom Gianakopoulos – John Cassavetes & Gena Rowlands

John Cassavetes was an actor’s director, which is to say: he was an actor who, when he wasn’t acting in other director’s projects, would direct and write and finance his own movies. If you are unfamiliar with his directorial work, you might recognize him in his various film roles: as one of the rough and ready soldiers in The Dirty Dozen, or the morally compromised father in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby.

Those who are familiar with the films he directed know that they dealt with difficult subject matters, attempting to say something about the human experience, about what it meant to fall in and out of love, and to be forgiven (or not) for our shortcomings.

I am hard-pressed to think of a Cassavetes movie that contains a happy ending, yet his movies still resonate decades after they were originally released. It is no coincidence that the strongest among them are those that star Gena Rowlands, his wife of 35 years: A Woman Under The Influence, Minnie and Moskowitz, Opening Night and Gloria. A Woman Under The Influence earned Academy nominations for both Rowlands and Cassavetes in their respective categories, something which the director himself would downplay.

Cassavetes‘ relationship with Rowlands was a complex but passionate one, and the couple was very open about when they disagreed, which seemed to be often. Both husband and wife were not afraid to go against the grain of what audiences expected of a movie, and were known to take risks with their films in an attempt to portray the emotional truth of a story.

It had not occurred to me until the writing of this truncated piece why it is that I respond so strongly to Cassavetes’ films, even the ones that do not seem to work for me: their stories reach in, lift me up and shake me by the shoulders. Depending upon my state of mind, they might even give me a smack or two across the face, just to make sure I’m paying attention. Then with another cuff of tough love, they send me on my way, buoyed by a renewed sense of understanding of my life and all its glorious inconsistencies.

As the films which resulted from these collaborations demonstrate, repeated experiences working together can allow for more open, honest and raw performances, as the actor and director develop a shorthand of trust with one another.

Knowing that they are the hands of a skilled director likely makes an actor more confident that their work will be used appropriately and to strong effect, creating a sort of symbiotic closed loop, where the talents of both parties help to continually enhance the other’s (Tim Burton and Johnny Depp likely being the exception that proves the rule).

Though many notable tandems have come and gone, there is no doubt that actors and directors will continue forging meaning bonds throughout the future, and in doing so, help to spur the art of film forward.

What’s your favorite actor/director collaborations?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Arlin is an all-around film person in Oakland, CA. He received his BA in Film Studies in 2010, is a documentary distributor and filmmaker, and runs Drunken Film Fest Oakland. He rarely dreams, but the most frequent ones are the ones where it's finals and he hasn't been to class all semester. He hopes one day that the world recognizes the many values of the siesta system.