Tribeca Film Festival Reviews: Around The World In Three Docs

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

As much as we might dream of doing it, we cannot all afford to travel the world. For some of us, the closest we will ever get to the dusty plains of East Africa, the riotous soccer stadiums of Brazil, or the elite clubs of New York is via the movies.

That’s why it is so fantastic that this year’s Tribeca Film Festival featured a wide variety of documentaries from around the globe. I only managed to squeeze three into my viewing schedule, but all three gave me the opportunity to enter new worlds that I had not previously had the privilege of visiting.

Tanzania Transit (Jeroen van Velzen)

Netherlands-born director Jeroen van Velzen spent the majority of his childhood living abroad in Kenya, India, and South Africa. He mined his childhood memories of Kenya for his first feature-length documentary, Wavumba, which earned him the Tribeca Jury Award for Best New Documentary Director in 2012. So it’s no surprise that van Velzen would return to Tribeca with his second feature, another Africa-set documentary titled Tanzania Transit.

This lovely cinema verite road movie follows three sets of passengers for three days and three nights on board a train crossing Tanzania: Rukia, a tough woman who has left her homeland of Kenya in search of a new life; Peter Nyaga, a gangster turned preacher who spends the entire journey offering blessings and prayers to his fellow traveler; and Isaya, a Maasai elder accompanied by his grandson, William, who is an aspiring performer in the big city.

Isaya is returning home after visiting William in the city, but he still cannot seem to wrap his mind around the notion that William wants to earn a living by singing and dancing – even after William shows him several videos of performances on his phone and tells his grandfather how much he got paid for each. The two Maasai men spend the journey dealing with blatant prejudice on the part of the other travelers, who see their traditional costumes and accuse them of being there to cause trouble and violence; even the well-spoken William cannot convince these men that their opinions of the Maasai are backward and unwarranted.

Meanwhile, Rukia, who is used to the behavior of backward-thinking men since she ran a bar in Kenya that catered to miners, tells the other women she meets on the journey about her previous relationships, including the man her parents sold her to as a child bride. It’s clear that various traumatic events in Rukia’s past have hardened her into the independent, outspoken woman she is today, the kind of woman who is perfectly comfortable drinking beer with all of the men on the train while also converting them in anger when one of them crosses her personal boundaries.

But the most fascinating of all of the passengers is Peter Nyaga. He doesn’t hesitate to outright claim that he is healing the sick when he prays over them, or to use religion as a way to sell copies of his book. One is immediately distrustful of him and his snake oil salesman ways, but one also cannot help but be drawn to him and his charismatic preaching.

Tanzania Transit opens audience eyes to a world that most of us will have rarely seen, and introduces us to characters whose stories are too infrequently told. There are no interviews with the camera or visible signs of a film crew, making it quite easy to forget that you are watching a film at all. Nor does Van Velzen attempt to assert a formal narrative arc of any kind upon his subjects. Instead, he settles for capturing him in all of their natural color and culture, allowing you to feel as though you too are a passenger on the raucous, impossibly bumpy train. Along the way, the train stops in various villages for food and other supplies, allowing us to snatch brief glimpses into the lives of people across East Africa.

For his beautiful and utterly natural camera work, cinematographer Niels van Koevorden received the Best Cinematography in a Documentary Film at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, with the jury noting, “To witness the care taken in the framing of each shot of this remarkable film conveys pleasure in and of itself. That the aesthetic rigor of each of these images also opens the space for us to contemplate the challenges of being human with such gentleness is transfixing. This is a movie that dares to have no beginning and no end.” Indeed, while the film might not have much of a beginning or an end, that doesn’t prevent Tanzania Transit from being utterly engaging throughout the entire journey.

Kaiser: The Greatest Footballer Never to Play Football (Louis Myles)

Whereas Tanzania Transit is so natural that one can easily forget that one is watching a movie, Kaiser: The Greatest Footballer Never to Play Football falls at the complete opposite end of the spectrum. Everything about it feels too ridiculous to be true, a feeling that is only accentuated by director Louis Myles’s heavy reliance on dramatic recreations of past events that may or may not have happened in the first place. Yet that is the whole point of the documentary: to expose the truth behind a story that blurs the boundaries between reality and fiction, starring a man who is essentially the Tommy Wiseau of international soccer.

Carlos Henrique Raposo aspired to live a life full of glamour and girls, just like the best footballers in Brazil. So, he used his resemblance to one of Brazil’s biggest stars at the time, Renato Gaúcho, to gain entry to that elite world. From there, he somehow managed to convince numerous soccer clubs in Brazil and around the world to offer him contracts to play for them as a professional footballer. And yet despite earning one contract after another, the man known as Carlos Kaiser – according to him, because he resembled German soccer legend Franz Beckenbauer, though according to one friend, it was actually because his chunky body resembled the shape of a Kaiser beer bottle – never actually set foot on the pitch during a competitive game.

Aided by a Bernardo De Paula voiceover that is as sunny as the sandy beaches of Brazil, Myles pieces together interviews with Carlos Kaiser himself as well as friends, footballers, journalists, and coaches to tell one of those tales that epitomizes the phrase “truth is stranger than fiction.” That Carlos Kaiser was able to con team after team into signing him through sheer bravado, just to live a privileged lifestyle, seems impossible in today’s world, where every single soccer player worth his salt has an edited highlight reel on YouTube. But in the 1980s, it was easy enough for Carlos Kaiser to convince scouts that grainy video footage of Renato Gaúcho scoring goals was actually of him.

In a film chock full of outrageous and amusing anecdotes, the most entertaining parts of the Kaiser: The Greatest Footballer Never to Play Football are actually the colorful sequences recreating key pieces of the Carlos Kaiser legend, including fights with fans and encounters with Brazilian mob bosses. Because of that, I found myself wishing that I was watching a narrative film depicting Carlos Kaiser’s life instead of Myles’s documentary, which periodically seems to be masquerading as a fiction film before remembering what it’s supposed to be doing. The film is just more fun to watch when it embraces the unbelievable nature of the story at its center.

The scenes involving the real Carlos Kaiser (who really does look, sound, and act like a Brazilian Tommy Wiseau), including some pretty wild interviews set in locations such as a glamorous hotel room where the aged “faux footballer” sits flanked by beautiful girls, fall flat compared with the rest of the film. Certain scenes seem excessively orchestrated just to elicit audience sympathy for Carlos Kaiser and as a result, they ring a bit false, even more so than some of the absurd antics he engaged in during his “playing” days. But by showing us how the myth is so much more enjoyable than the man, Myles also helps us understand why the man created the myth in the first place.

Studio 54 (Matt Tyrnauer)

Everyone who lives in New York nowadays is either nostalgic for the 1970s or relieved that they’re over. You’re either grateful that Time Square got cleaned up or you’re annoyed that all of the prostitutes and pickpockets have been replaced by costumed characters looking to take photos with tourists and their kids. It might have been a bit of a mess, but there’s no denying that New York had more character in the 1970s than it does today. And there’s no place in the history of the city that epitomizes that character more than the legendary Studio 54.

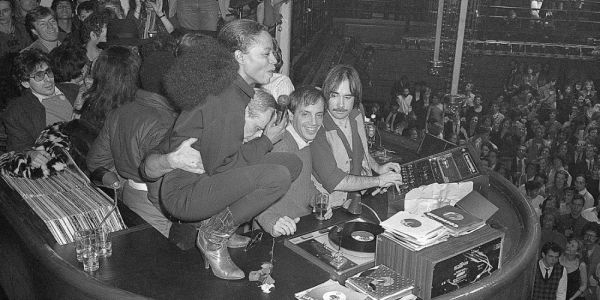

In his documentary Studio 54, director Matt Tyrnauer takes us behind the velvet ropes of the infamous disco, a celebrity hotspot where anyone could feel free to be themselves once they got past the notoriously tough gatekeepers at the door; your gender, sexuality, and social standing didn’t matter inside Studio 54. The club was the brainchild of two Brooklyn-born college friends: an introverted lawyer named Ian Schrager and an outgoing yet closeted restaurateur named Steve Rubell.

Rubell was the face of Studio 54, hobnobbing with celebrities and making sure that they all had the drugs they needed, while Schrager was the brains behind the club’s famous interior design. But some financial missteps – mostly chalked up to the impetuousness of youth and the consequences of almost instantaneous fame – led to the downfall of the club and its owners less than three years after Studio 54 opened its doors. Yet despite the brief time that Studio 54 was open, the impact of the club on New York nightlife that will never be forgotten.

Rubell has since passed away, but Tyrnauer peppers his documentary with delightfully eye-opening interviews with Schrager, a good-natured, gruff-voiced hospitality magnate with fond memories of Studio 54 and his best friend and business partner. At the heart of the film and the club’s success is the deep friendship between these two men, which lasted until Rubell’s untimely death from AIDS in 1989. In addition to Schrager, we hear from Marc Benecke, the famous doorman who was chosen for the gig over all of the other security guys because he was the best looking of the bunch, and various other members of the club’s staff, as well as famous regulars like Nile Rodgers.

Combining these present-day interviews with old footage of the club at its hedonistic heyday, rich in glitter and film grain, Tyrnauer weaves together a definitive history of a place that encapsulated an era. As Schrager and company reminisce about the good times as well as the bad, the grittiness as well as the glamour, it is impossible not to feel like you missed out on something special by not being there – even if, like me, you don’t really have a burning desire to dance all night while high on cocaine.

Studio 54 was so much more than just a place to party; it was a place where you knew you could truly let loose and be yourself, with no fear of judgment. Watching the film will make you nostalgic for an era of utter freedom that we seem to have lost in the forty years that have passed since.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. When not watching, making, or writing about films, she can usually be found on Twitter obsessing over soccer, BTS, and her cat.