The Beginner’s Guide To Abbas Kiarostami, Director: Essential Viewing For Tumultuous Times

Christopher Connor completed his B.A. in Film and Media Studies…

It hardly needs to be stated that we have entered into frightening times, both here in the U.S. and internationally. Although now temporarily blocked by a Washington federal judge, Trump’s executive order banning refugees and nationals from seven predominantly Muslim countries – Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen – seems far from over.

It’s important to remember that there has not been one terrorist related death in the U.S. for many decades linked to these seven countries. And yet, here we are. Hundreds of millions of people painted in one broad brush because of an irrational fear. Because of prejudice, and racism. And while recent polling has suggested that a narrow majority of U.S. citizens oppose this ban, we can still benefit from taking a look at what these Middle Eastern countries have to offer, and what they are trying to say.

One way we can achieve this is by taking a look at cinema, an art form that has the potential to transcend boundaries unlike any other. Film has the incredible ability to reach people and connect in ways unprecedented. We can be transported to a different world and experience the lives of others, breaking down boundaries and preconceived ideas.

One filmmaker, Abbas Kiarostami, excelled at this. And now, with Iran responding to Trump’s ban with a U.S. ban of their own, it’s essential we look back on Kiarostami’s work to remember that these “others” are just as human, with wants, desires, and fears.

A Brief, Brief History of Iranian Cinema

In the early 1950s, cultural and intellectual changes were taking place in Iran that allowed film to be seen as a cultural category, rather than simply a commercial one. Iranian films at the time were often poor commercial imitations of popular Hollywood and Bollywood films, known as Film Farsi. But as these shifts occurred, it helped spawn the Iranian New Wave, with films like Darius Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969), a film which follows a man who owns the only cow in his village, and after the cow dies, his descent into insanity. Mehrjui’s film, along with a handful of others, challenged the Film Farsi films by taking an intellectual, philosophical, and humanist approach to cinema.

These films were very much influenced by the Italian neorealists that came before them. Like the neorealist films, these Iranian films were incredibly humanistic. They focused on the marginalized, disenfranchised, and the poor. They used on-location shooting and utilized many non-actors, creating an authenticity not yet seen in Iranian film. These films focused on village life rather than the urban, offering a new identity that many Iranians were more comfortable with. Ultimately, they were much more relatable both to Iranians themselves and to international audiences.

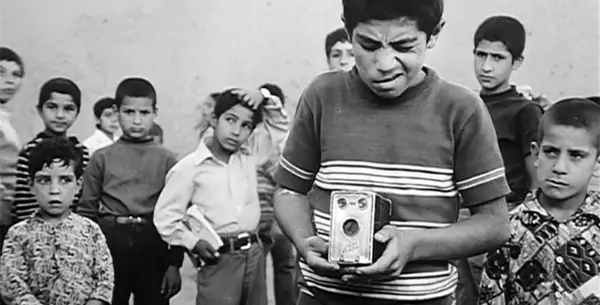

Bread and Alley (1970)

Abbas Kiarostami was himself a product of this Iranian New Wave. He started his career before the Iranian Revolution (1979), working on commercials, and then moving on to shorts and educational films for children. These educational films include his debut short, Bread and Alley, a simple and touching story about a young boy being confronted by a hungry dog on his walk home. Much to the boy’s dismay, no one bothers to help him. He solves the problem by feeding the dog a piece of bread. The dog quickly becomes his friend and they walk home together. But once the boy is home, his mother shuts the door on the dog, refusing to let him in.

The film is told in a straightforward and simple manner. Yet, there are themes beneath the surface that form the basis for a lot of his later work. There’s the fear of being alone in the world, and of feeling small and helpless. There’s the theme of breakdown in communication. There’s a particular scene in the film where the boy tries to use a man passing by as a shield for the dog. We see clearly that the man has a hearing aid in, unable to even hear the boy if he were to ask for help. He is effectively cut off from the child’s world, leaving him to fend for himself.

The boy is alone and seems to be at odds with everything around him: the adults, the hungry dog, and the narrow alleyway leading him into potential danger. But when the boy gathers the strength to face the dog and uses his cunning to appease him with a piece of bread, his fears are quickly assuaged when he realizes that the dog was merely hungry. The fear was simply a misunderstanding. And when they reach home, and the dog is shut out, it’s a sad reminder that empathy and understanding is an active process. It’s easy to shut things out and forget about them. It sometimes takes strength to empathize.

To reinforce this pattern of misunderstanding, the film ends with another boy walking down an alley with a bowl of milk. It ends in a freeze frame of the boy, who is frightened by the dog’s presence. Fear and the process of understanding is continual, but essential.

Kiarostami has a way of working with children that is truly exceptional. He treats them on an equal footing with adults, and often times more sympathetically. Adults are often portrayed as being uninterested or unable to relate to children in any way, too stuck in their own modes of thinking. He clearly empathizes with children and their world, understanding that they are often overlooked, even though their concerns and ideas are important and valid. We can see this idea start forming in Bread and Alley, and it is further developed in his first feature film, The Traveler (1974), as well as the film that brought him real international attention, Where is the Friend’s Home? (1987).

The Traveler (1974)

In The Traveler, a young boy, Qassem, is at odds with the adult world around him. He’s not unlike Antoine Doinel in Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959). Rather than do homework, he plays soccer in the alley. He makes excuses as to why he’s late for school, and reads soccer magazines in class. And because of it, he’s constantly punished and berated. Ultimately, he wants nothing more than to visit Tehran to see his favorite soccer team play.

To pay for his trip, Qassem attempts to steal money from his mother, for which he is caught and scolded. He then comes up with a variety of schemes and tricks to get the much needed funds, and finally sells his own team’s soccer balls and goal for a long bus trip to Tehran. When he arrives, he ends up buying an overpriced ticket for the match, but realizes he’s several hours early. To kill time, he wanders around, only to fall asleep, and have nightmares of being punished for all his misdeeds. Upon waking from his nap, he finds out that the match is over.

While the ending might be read as the inevitable comeuppance for all of Qassem’s misdeeds, Kiarostami instead has us sympathize with him. Rather than us be happy that Qassem didn’t get what he wants, we share in his despair. Qassem seems alone in his world, completely alienated from adult society. Kiarostami wants us to better understand him, and while not necessarily wanting us to condone his small scams and trickery, makes a case as to why we should really consider children as human beings with all the complexities of adulthood.

Where is the Friend’s Home? (1987)

Where is the Friend’s Home?, the first film in his Koker Trilogy, might have an even simpler premise than the first two films discussed. It deals with a young boy named Ahmed, who realizes that he accidentally brought home a friend’s homework book. This friend is already on bad terms with the teacher, and if he messes up one more time, faces expulsion. So, Ahmed takes it upon himself to find the home of the boy and deliver his notebook.

Despite his efforts, Ahmed can’t seem to find him, and all the adults in the film are of no use. He fails in ever finding his friend. The following morning, Ahmed comes to class late, but just in time to hand over his friend’s notebook. He whispers to him that he has done the homework for him. The teacher looks over their work, praises them, and moves on. It’s an ending that is so simply effective in its use of suspense, and ultimately so incredibly touching, that it’s hard to imagine anything that can top it.

This is yet another boy-on-a-quest film with a simple story on the surface. But similar themes of communication are at play. There is one very telling scene where Ahmed returns from his first attempt to find his classmate. He runs into his grandfather who asks him what he’s doing. When Ahmed tells him that he’s been to the town over to give back his classmate’s book, to no avail, his grandfather brushes it off without a second thought, despite Ahmed’s obvious anxiety about the situation. The grandfather then tells him to go grab him cigarettes. Ahmed obeys and runs off.

Instead of taking off with Ahmed, the camera stays on the grandfather and his friend. They have a conversation about the necessity to discipline children, even with violence. He calls Ahmed lazy, and implies he’s inattentive because he hesitated to retrieve his cigarettes. His friend questions him, asking: if he obeyed immediately, would he still hit him? He answers yes; that even if he did nothing wrong, he’d find an excuse to hit him so he could learn some discipline.

In reality, Ahmed’s quest is altruistic and commendable. He’s not lazy, but actively conscientious and kind. But the grandfather is blind to this, and to Ahmed’s entire world. This scene goes on for a whole six minutes, until Ahmed finally returns. Kiarostami couldn’t have made it any clearer: the adults don’t understand. It’s almost as if the adults are choosing to ignore the children.

Close-Up (1990)

Kiarostami moved away from using children as his protagonists with his film Close-Up. While still dealing with themes of communication breakdown, Kiarostami adopted a more postmodern approach to filmmaking, becoming highly self-reflexive. He explored truth with a compelling mix of fiction and reality.

Close-Up exemplifies this shift in exploration. It is an incredible film that tells the true story of Hossain Sabzian – a man obsessed with film – who ends up impersonating the Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf after meeting a girl on the bus who notices him reading a screenplay of one of Makhmalbaf’s films. For no real apparent reason, Sabzian tells her that he is, in fact, the director, and because of this meets with her family over several weeks until he is ultimately found out and sent to trial.

What is so amazing about Close-Up is that Kiarostami not only mixes real documentary footage of the trial with the events leading up to it, but he actually got Sabzian and the family he duped to recreate the events that happened to them for his film. As an audience, we witness the actual unfolding of the trial mixed with a recreation of the events that led to it – by those actually involved. And to further complicate things, Kiarostami actually inserted himself in the courtroom proceedings, going as far as suggesting questions to be asked of the defendant and helping him script Sabzian’s testimony.

The film questions the ideas of identity, of the auteur, and essentially cinema itself. It’s not presented as a documentary, nor like a piece of simple fiction – it lies somewhere in-between. Unlike the child-centered films of his earlier career, this film is not simple on the surface, and its complexities are laid out before us. We are forced to engage with these ideas of truth and reality.

The following years saw Kiarostami explore this self-reflexive and metaphysical approach to filmmaking with the two films that complete his Koker Trilogy: Life, and Nothing More (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1994). In the former film, the “director” (not played by Kiarostami) of Where is the Friend’s Home? searches for the two young boys who acted in the film after a devastating earthquake hit the region. In the final film, Kiarostami focuses on characters who end up being involved with the filming of Life, and Nothing More. But it was with his film Taste of Cherry (1997) that brought Kiarostami his most acclaimed work, becoming the first Iranian film to win the Palm d’Or.

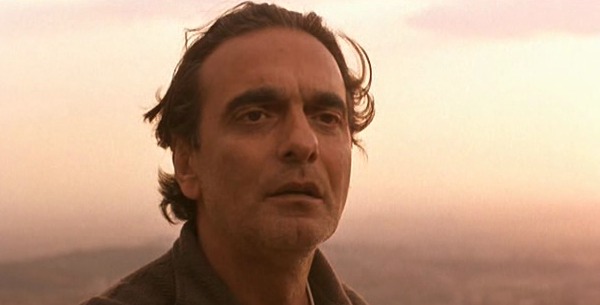

Taste of Cherry (1997)

Taste of Cherry brought Kiarostami back to his extreme minimalism, straightforward narratives, and simple storytelling. We are introduced to Mr. Badii, who drives through the outskirts and hills of Tehran in a search for someone to help him with a task. For almost twenty-five minutes, we are unsure of what he wants, and when he approaches various people to enlist their help, we – like them – wonder if he’s a gay man cruising. Eventually, we realize he needs someone to help him commit suicide. He plans on overdosing on pills, climbing into a grave he’s dug, and having someone subsequently bury him in accordance to Muslim tradition.

After many long takes and scenes of Badii driving through the beautiful landscapes of Tehran, and of conversations with people he’s propositioned – and their ultimate refusal – Badii finds someone who will throw earth on him if he finds him dead the next morning. And while we watch Badii climb into his grave, a thunderstorm erupts, and eventually the screen is cut to black.

When the film fades back in, we aren’t with Badii anymore. We are, in fact, watching documentary video footage of the actual filming of Taste of Cherry. We see soldiers marching through the hills, the camera crew recording, the actor Homayoun Ershadi – who played Mr. Badii – walking around, and even Kariostami himself. The soldiers stop to pick flowers, and finally we watch a car turn around the bend of a hill, just like we saw countless times previously in the film.

The film is a wonderful, quiet contemplation on life and its meaning. We watch a man drive through the beautiful vast landscapes that have become a staple in Kiarostami’s work, recalling the beautiful images in Where is the Friend’s Home? It’s a film of true experience. We feel physically and emotionally connected to Badii’s journey with the drawn out repetitive, rhythmic driving sequences, the sound of the countryside and distant city, the slow – but always intriguing – conversations. We are hypnotized by the entire experience.

Like his earlier work, the film is incredibly simple on the surface. But hidden just beneath is a world of complexity. Unlike some of his earlier films, Taste of Cherry still implemented his new penchant for self-reflexive filmmaking with the ending. This time, though, some detractors and critics saw the self-reflexive ending as a way to simply remind the viewers it was all make believe and appease the government censors. But this feels off the mark and misinformed. It’s worth mentioning that the film was first denied export to Cannes by Iranian officials due to the problematic issue of suicide, even with the attached ending. Furthermore, the film was banned for almost three years in Iran.

The bookend really feels like a joyous celebration of life and its complexities, and this is especially felt when Louis Armstrong’s “St. James Infirmary Blues” kicks in. It’s the only non-diegetic sound we hear, and it truly does create an emotional, visceral reaction. As the song plays, we watch the soldiers pick flowers and mess around on a grassy hill. It isn’t just a reminder that the film is fiction, but a sort of playful provocation, asking us to engage in what is real and what isn’t.

We don’t know if Badii died, but that doesn’t feel important anymore. Instead, what’s important are the questions we are left with. Why suicide? What were to happen to him if he did commit suicide? What would happen if he chose to keep on living? What’s important in our lives and what is the truth? It shows us the power cinema can have to interpret life, to mold it into something new. It recalls Dziga Vertov’s “kino-eye,” the idea that the camera has the ability to present us a truth we as viewers are unable to see with our own naked eyes.

The Wind Will Carry Us (1999)

Two years after Taste of Cherry came The Wind Will Carry Us, a film about a man, Behzad, and his fellow coworkers, who travel to a remote village to document a woman’s death and the ceremony that follows. What was supposed to be a quick visit turns out to take weeks, when the woman defies expectations. She refuses to die, forcing Behzad to live in this village that feels stuck in time. Behzad and his coworkers are eager for the woman to pass away so they can do their work and leave, because living in the remote countryside, hundreds of miles away from modern civilization, proves more difficult than expected.

The Wind Will Carry Us is incredibly lyrical and poetic. The repetition of shots, such as Behzad constantly driving up the hill to find cellphone service, creates a wonderful rhythm. Throughout the movie, poems are constantly recited, emphasizing the lyrical quality of the film. Kiarostami often foregrounds his landscapes, creating larger-than-life characters out of them. And here, it’s no different. Cars and motorcycles weave in and out of the devastatingly beautiful countryside. It’s a motif carried throughout so many of his works, and it never grows tiring.

Like much of Kiarostami’s work, in particular Taste of Cherry, The Wind Will Carry Us keeps most of what we want to know just out of reach. But Kiarostami really holds out here. He doesn’t provide us details that we may feel are essential to understanding the plot, so it’s not uncommon to feel like you may have missed something. Through careful viewing, the purpose of the men’s visit reveals itself. Yet, it’s what happens during the visit that’s important, with the plot taking a backseat.

Similar to his early films, Kiarostami explores a theme of lack of communication, or maybe more appropriate, Behzad’s disconnection to this new world he finds himself in. His main source of connection to Tehran and the modern world is his cellphone, which hardly ever works. The only time it functions correctly is when he drives up to a hill high above the village, and even there, connection is spotty.

This disconnection reflects Behzad’s disconnection to the actual village he’s staying in. He’s going to this place where he has no connection with the people who inhabit the land, or their way of life, and basing his work off that. And here is where we see Kiarostami’s preoccupation for self-reflexive filmmaking back at work. Behzad acts as a surrogate for Kiarostami. Much of his own work is based on going to places he has no deep connection with, and then making films about them. In this sense, the film can be seen as partly autobiographical.

This brings up interesting questions of exploitation, trust, and truth. It forces us to question Kiarostami’s role as filmmaker, and our role as viewers. Are we also complicit in this possibly exploitative process? Maybe it’s not exploitation, but then again, where do we draw the line? How does our disconnection to these other worlds, to these other people, affect how we feel about them? That’s the power of Kiarostami’s cinema. He uses his films, and their often ambiguous meaning, to help us engage with larger ideas.

Essential Viewing for Tumultuous Times

These films are essential viewing for anyone interested in Abbas Kiarostami, or Iranian and Middle Eastern cinema in general. On the surface, they’re simple explorations of Iranian life and problems. Scratch the surface, though, and you are forced to engage with challenging ideas about humanity. By examining these films, we can see how Kiarostami was interested in a myriad of truths, reality, self-examination, and identity. He was interested in our inability to meaningfully communicate with people who may not be exactly identical to us.

We are currently in a time where this effort for communication is of utmost importance. We need to take steps back to examine our own prejudices and ideas. We need to understand that there may be different truths and different ways of perceiving the world, and that should not be viewed as a threat.

The vast majority of people in Iran and in the Middle East aren’t monsters hell-bent on destroying the U.S. and the rest of the world. They are human beings that want to live their lives. We need to reexamine these ideas and misconceived threats. Iran poses no tangible danger to us. The other six countries listed in Trump’s ban do not either. Statistics and recent history prove that.

None of this is to ignore that Iran truly is a repressive regime, a theocracy concerned with controlling its people. But it’s a reminder that the people are not the government. And most of those people are far more similar to us than they are different. It’s far too easy to make blanket statements about an entire group of people, to make them “others.” But at the core of Kiarostami’s films are humans. It’s humanity. It’s the humanization of the unfamiliar. Kiarostami makes his characters feel so exceptionally real, that we can’t help but to see parts of ourselves reflected back to us. And because of that, the barrier between us and them disappear.

What are some other great Iranian or Middle Eastern films that work as a window into the lives of others? Discuss in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Christopher Connor completed his B.A. in Film and Media Studies and his minor in Italian Studies at UCSB. While in school, he won several awards and scholarships for his screenplays and academic writing. They include the Paul N. and Elinor T. Lazarus Scholarship, the Dorothy and Sherrill C. Corwin Award, and the Alexander Sesonske Prize, among several others. If he’s not busy writing, he enjoys reading, watching films, and eating lots of vegan pizza.