Interview With Elliot Grove, Founder Of Raindance Film Festival And The British Independent Film Awards

I'm a copywriter with a passion for film and screenwriting.…

Elliot Grove’s life should be made into a film, virtual reality’s going to be the next big thing and Sacha Baron Cohen hasn’t always been funny. Those are just three of the things I discovered when I went along to interview Grove, founder of the Raindance Film Festival and the British Independent Film Awards.

Discovering Raindance

I grabbed the chance to ask Grove for an interview at a recent Raindance Open House event, held to introduce filmmakers to Raindance and what it can do for them. Generously, he said yes, and a week later I went down to London to interview him at the Raindance offices near Charing Cross Station.

I bumped into Grove on the street, making calls on his mobile. He explained Raindance is an O2 black spot, which is why he always goes outside to use his phone, and showed me the way to the door I needed, saying he’d just be a few minutes.

Once inside, it was great having time to sit and take in the view. Raindance is a rabbit warren of offices and production studios in the basement of a typical London townhouse. The first thing I noticed was the old red velvet cinema chairs, reminiscent of the faded glamour of movies gone by, arranged in rows in the waiting areas. The office itself was a quiet buzz of activity, the small Raindance team working hard, surrounded by everything you can think of to do with film; books, posters, old film reels in cans, awards left over from the last Raindance Festival in 2015…

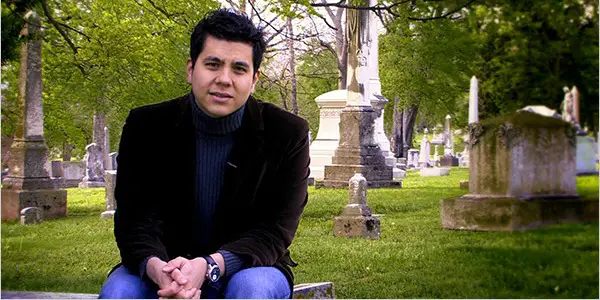

Grove returned and apologised for keeping me waiting. He has a calm, laidback way about him, but once he gets talking about the things he loves, you can see the passion, the determination and the hard work he’s put in to get this far.

Grove’s early years

We find a quiet spot outside the production studio and Grove takes a seat opposite mine, on the well-loved cinema chairs. He’s wearing his trademark black jeans and trainers. I start by asking him about himself and it turns out I’ve visited his hometown of Kitchener, a small city around 100km west of Toronto, Canada. Grove explains:

“I went to art school in Toronto, and before that, lived with my mother and sister in Kitchener. My father was killed in Somalia, where he worked as a missionary.”

As a child, Grove grew up on a Mennonite farm, a strict Christian order, similar to Amish communities in the US. It meant he couldn’t watch TV or films. I asked him which film had ignited his passion for the movies, an intriguing question at the best of times, but even more so when film is a complete taboo.

“I was always told never to go to the movies, because the devil lives there. Then, one day, when I was sixteen, I was sent into town to do chores. I had to wait around for a while and discovered it only cost 99 cents to visit the movies, which to me, meant getting to see what the devil looked like. I went in, and it was a bit like church, with the rows of seats.

“The movie showing was Lassie Come Home and I cried like a baby. When it finished, I went down the front and felt the screen, wanting to know where the magic had gone to. It’s probably not very cool for the founder of a film festival to say, but when people ask me about the film that sparked my love of movies, I always say Lassie Come Home. I remember everything about that experience, down to the fact it was a really hot summer’s day.”

I tell Grove about my first cinema experience and say his must have been amazing for him, given that he didn’t know anything about the movies. He says: “It may as well have been moon walking.” He laughs and reiterates the fact he had two things drummed into him as a teenager: “Never go to the movies and never have sex standing up, it can lead to dancing.”

How it all began

After art school, where he studied bronze casting, Grove went on to work with several sculptors, before first coming to London as a stage hand for the BBC. He returned to Toronto as a scenic artist, working on scores of feature films and hundreds of commercials, but was inspired to come back to the UK after having children, in the late 1980s. Just like the twists and turns of a film script, it wasn’t plain sailing for Grove.

“I got into property but went bust in the early ‘90’s recession. Being broke forced me to do jobs I’m not proud of, including being a debt collector, but I wasn’t very good at it. I’d come back to the office with a carful of TVs, rather than earning my commission by collecting the money people owed. I’d just explain to them it was better for them to give me their TV and have their debt cleared, instead of having to part with their cash.”

Adversity proved to be a silver lining for Grove, as he set up the Raindance Film School in 1992, the Raindance Film Festival in 1993 and the British Independent Film Awards in 1998. Throughout the interview, Grove jokes a lot about his bank manager hating him, but sacrificing financial security for the chance to do what he loves has proved lucrative in a different way for Grove.

It’s also proved lucrative for the British film industry and the thousands of filmmakers who have benefited from Raindance’s support. I asked Grove why he founded Raindance in the first place, apart from regular jobs not working out. It’s hard to remember a time when the UK wasn’t making films, but that was pretty much the case in the early ‘90s. Grove explains:

“The people who were making films in the UK in the ‘70s moved into TV in the ‘80s, motivated by the chance to earn a regular paycheck, which is understandable. When kids started making movies again in the early ‘90s, there was nowhere for them to show their films. There was only the London and Edinburgh film festivals and it was so unusual to have British films submitted at that time, they were often put into the world cinema category. So I decided to start the Raindance Film Festival to celebrate these new British films.”

Grove tells me it took a few years for the festival to get off the ground, because of these wilderness years and British film goers themselves. “I discovered something quite, well, nasty about British filmgoers [at that time] – they were snobs. They didn’t see any government or big brand logos so didn’t take the festival seriously.” But the signs of Raindance’s influence were there from the beginning. In 1993, the first Raindance Film Festival held the first ever public screening of What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, starring a 14 year old Leonardo DiCaprio.

Let’s do it

Justifiably, Grove is proud when he tells me Raindance is now listed among the top 50 must-attend film festivals in the world, by Variety magazine. He goes on to tell me how Raindance has grown organically since the early ‘90s, and about some of the first filmmakers Raindance supported.

These include Edgar Wright, who made his first film A Fistful of Fingers (1995), with Raindance’s help and was also Grove’s first intern. Wright went on to become a hugely successful director and writer, known for films like Shaun of the Dead (2004), Hot Fuzz (2007) and Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010). Also, a young Christopher Nolan, who used Raindance’s offices as a production base to make the film that would go on to be Memento (2000), while working at Boots the chemist during the week.

Surely, those two stories alone should inspire budding filmmakers to give it a go, whatever you’re doing at the moment?

Raindance’s philosophy is all about helping people make films, not teaching them about filmmaking. Grove says:

“With the help of my amazing team, Raindance has created an ecosystem of people interested in film, around the world. Some people want training in different film crafts like producing, directing or editing, others are drawn to our practical, hands-on, tailored post-graduate degree, many join as members or come along to our events, to meet and work with other like-minded people, some submit films to our festival and the British Independent Film Awards…whatever they come for, we say ‘let’s do it’.

“Growing up on a farm, I was told to look for patterns, in nature and animal behaviour. Maybe because of that I noticed a pattern in many film schools…they teach filmmaking but they also teach all the reasons why you can’t do it, because it’s too tough to break into movies, it’s too expensive, et cetera. Here at Raindance, we say you can and everything we do is about helping people make the films they want to make.”

(You’ll make a film even if you go along to one of Raindance’s one-day courses).

Revolutionary technology

We talk about some of the amazing films people have made using iPhones, including Tangerine (2015) and Searching for Sugar Man (2012). Grove tells me it’s this ability to change with the times that has kept Raindance at the forefront of film for 24 years.

“Things have changed a huge amount, back when we started, you had to shoot film on 35mm, then came digital.”

He’s equally passionate about the changes in the way films are watched. “February 15, 2005, that’s when YouTube was born, and now there’s Netflix of course.” It’s impressive he remembers the exact date, but it makes perfect sense given Raindance’s ‘let’s do it’ ethos.

Now, filmmakers can make a film on their phone and upload it directly to an audience of potentially millions, billions of people. As Grove says, this means there are a lot more bad films out there, but on the flip side, it makes it a lot easier for filmmakers to pursue their craft, get noticed and earn a living outside of the mainstream film industry.

He uses the British film and video creator, Thomas Ridgewell (TomSka), as an example, going from a bedroom hero working from his parents’ house in London, to earning “a million pounds a year from comedy shorts broadcast on YouTube”.

The next big thing

However, Grove thinks the next big seismic shift will be virtual reality (VR), heralded by the launch of things like Google Cardboard, a VR viewer that works with VR apps on your smartphone so you can watch VR content for just a few dollars.

“VR has been bubbling along in the geeky underworld for a while, but now it’s moving into the mainstream. It’s going to be the biggest thing since YouTube in 2005.”

It’s clear Grove is excited by the prospect of a seismic shift in film. He goes to get a Google Cardboard viewer and then shows me a short VR film called Take Flight (2015), broadcast by the New York Times. It’s amazing, taking you on a 360 degrees journey around the film’s cityscape, up into the sky, as you move through the world it creates.

But it’s not just the technology that’s ignited Grove’s imagination, it’s what it means for storytelling.

“VR is great for things like sport, music or news reports, but for film, we’re going to have to look to the past to learn how to tell stories with it, back to art forms like immersive theatre. Imagine this, I’m watching a VR film and in it, I’m looking at you, sitting on the couch opposite me. I hear a bang off to my right somewhere. Instinctively, I turn my head to the direction of the noise and get distracted. I turn back and you’ve been murdered.

“Or, if I hadn’t turned my head, I could’ve seen you being murdered. Maybe right now, while you’re writing this down, someone is working out how to tell stories in VR, in a bedroom, at a bus stop, on a park bench, in China, pushing a barrow in India, who knows. It’s this that gives Raindance meaning, because we’re here to help people work it out and make those films.”

Grove explains how whereas changes like YouTube and Netflix have taken existing content and broadcast it in a different way, VR demands new content, in much the same way as filmmakers had to adapt to sound in movies, or colour, way back in the past.

The burning question

I ask Grove if the lack of women and Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) professionals in the film industry is something he sees reflected at grassroots level, at Raindance events for example, or if it’s something that happens later, when people try to break into the mainstream.

He says there’s a pretty equal mix of men and women at Raindance events like Open House (something I’ve seen for myself) and people from all backgrounds too, in terms of ethnicity and age. At the last Raindance Film Festival, 26% of the films shown were directed or produced by women, and there are more women than men on the British Independent Film Awards judging committee. Grove says: “Traditionally, film has been dominated by young, white, Anglo Saxon males, but we are seeing changes.”

He also adds it’ll take time for these changes to feed up to Hollywood, before telling me that women-led stories are amongst the most profitable, underlining the illogicality of it all.

Can a film change the world?

At the start of the interview, Grove promises me half an hour, but we’ve been chatting for over an hour. Topics include Grove’s admiration for editors; his view that the revolutionary potential of technology won’t change the world for the better, because it’s things like the banking system that needs to change. The lack of investment in culture being a worrying sign of the decline of civilisation; and the importance of championing free speech by screening controversial documentaries like House of Numbers: The Anatomy of an Epidemic (2009), which explores the US medical industry’s link to HIV/AIDS and went against the tide of public opinion when it was screened, as well as the less controversial ones.

Talking about all these issues makes me realise why organisations like Raindance and the ability of independent filmmakers to tell their stories are so important. A film may not be able to change the world overnight, but they can get us thinking, questioning, exploring, understanding, feeling, seeing things in a different way, talking…outside the views fed to us by mainstream media for example.

It leads us onto a really interesting idea that anyone with something to say can be a filmmaker, or as Grove puts it:

“I’m exploding the talent myth. Sure, people have a natural aptitude for different things, but I don’t think one person is more talented than another. Skills are acquirable. What we call talent really comes from hard work and practice, practice, practice. So if you want to be a filmmaker, find your story and make it. Everyone will say you can’t do it, but don’t listen, do it, again and again and again until it’s great.”

He ends by telling me a funny story about a young, would-be comedian that came to a Raindance course on stand-up comedy. He was so hopeless, the course lecturer even asked him if he was sure stand-up comedy was for him. The young man in question was Sacha Baron Cohen, underlining Grove’s point that talent (and success) is about hard work and practice, practice, practice.

So there you go, there are no excuses. If you have an idea and a smart phone, get to work.

Find out more about Raindance at raindance.org

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

I'm a copywriter with a passion for film and screenwriting. I love most film genres but especially thrillers, science fiction, movies based on classic literature and films that can't be pigeon-holed.