Two things are true about Leni Riefenstahl: she was an immensely talented filmmaker, and she used those talents in the service of the Nazi regime, creating infamous propaganda films like Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938) that spread hatred and glorified Nazi ideals through masterful use of camera angles, movement, and montage. However, in the years following World War II, Riefenstahl refused to admit any culpability for her Nazi-era activities, claiming that she was entirely ignorant of the horrors of the concentration camps and made her films not as a fervent believer in Nazi ideology, but as a hired hand who kept art and politics separate. Was this true, or was it yet more impeccably created propaganda, designed to restore her reputation and allow her to continue her career?

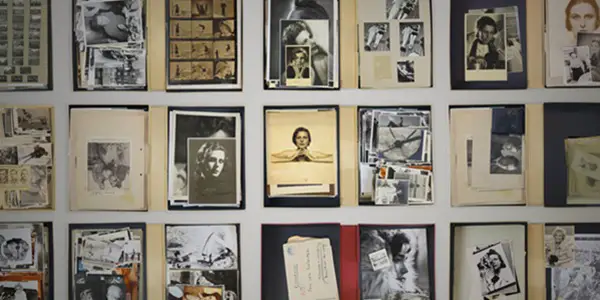

In the fascinating and infuriating new documentary Riefenstahl, writer and director Andres Veiel delves into the more than 700 boxes of archival material Riefenstahl left behind upon her death in 2003 at the ripe old age of 101—including private phone conversations she herself recorded—to discover who she really was behind the reels of carefully crafted and curated images. The result is a portrait of an unrepentant woman who expertly manipulated the public’s perception of her while privately mourning the loss of her “murdered ideals.” It’s also an uncomfortably timely examination of the fascist aesthetics and ideology she popularized with her work, which are once again rising in popularity today.

Archive Fever

You would be within your rights to wonder why we need another movie about Leni Riefenstahl. In 1993, to coincide with the release of Riefenstahl’s memoirs, the three-hour documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl was released, complete with heavy involvement from its nonagenarian subject. Indeed, Riefenstahl makes use of scenes from the final version of this earlier film as well as behind-the-scenes footage that shows us exactly how much control Riefenstahl exercised over what appeared in the finished film. In other words, no matter how honorable the filmmakers’ intentions may have been, the fact that Riefenstahl was still alive and well to rage over the slightest implication that she was a devoted Nazi automatically makes The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl a questionable document of her life and career.

Riefenstahl has now been dead for more than twenty years, and her much younger partner, Horst Kettner, recently passed away as well, meaning that there is finally no one left from her loyal circle to come to her defense—which is good, because as one sees in Riefenstahl, defense is more than she deserves. Based on my own research, I have always gone back and forth between thinking of Riefenstahl as a fanatical true believer and Riefenstahl as a narcissist and opportunist who was willing to go along with anything for the sake of her artistic career; in this film, we see that she was both, and never stopped being both for the duration of her exceptionally long life.

Riefenstahl is constructed entirely from historical archival material. Except for some narration, the film relies almost entirely on its subject’s own words and images, whether they be scenes from her most famous films as an actress and director to interviews she participated in decades after World War II. In one of the film’s most enraging sequences, an elderly Riefenstahl appears on a 1970s German talk show alongside another woman from her generation who confronts Riefenstahl for making what she describes as “Pied Piper” films. Riefenstahl’s response is angry and defensive, full of repeated claims that she was ignorant to the extent of Hitler’s evil. What makes the clip so anger-inducing is not just Riefenstahl’s self-righteous attitude, but the way the live audience in the television studio is so obviously on her side, applauding her every word. Afterward, she received many phone calls and letters of support from the German public, who saw Riefenstahl’s fervent denials of knowing anything about the Nazis’ many crimes against humanity as proof they could use to deny they ever knew anything either.

Gaslight Gatekeep Girlboss

As we see throughout the film, this was all part of Riefenstahl’s lifelong attempt to rehabilitate her reputation after the war, including her acclaimed books of photography documenting the life and culture of the Nuba people (a continuation of the preoccupation with and fetishization of Black bodies that began when she filmed Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics). Everything she did in public, from appearing on television to defend herself (but only if no images of Nazi atrocities against Jewish people were involved, please and thank you) to filing lawsuits against those who dared to question her self-proclaimed political inexperience and naivety, was designed to ensure she’d be remembered not as a perpetrator, but as a victim herself—someone who was hoodwinked by Hitler rather than one of his inner circle.

Veiel repeatedly contradicts Riefenstahl’s claims of innocence with materials from her own archives that incriminate her, and it’s hard to think of a more deserved fate for one of history’s most prominent propagandists than for her own words and images to be used against her in this way. The film isn’t told in anything approaching chronological order, yet it flows smoothly and is edited cleverly. We see Riefenstahl in The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl, still proud of the shots she created in Triumph of the Will almost sixty years earlier, claiming that the movie focused on peace and never mentioned racial purity; the film then immediately cuts to a clip of Hitler preaching racial purity in Triumph of the Will that proves her a liar. Veiel also uses her words to show us how much she privately aligned with Nazi ideology, juxtaposing a recorded phone call accusing the publication Bild of having a “Jewish slant” with clips of Goebbels saying similar things about the Jewish people.

It’s hard to pick out what is the most grotesque story shared in Riefenstahl, but the one I keep coming back to is the one about the Jewish prisoners in Poland who were massacred after she complained about them ruining the aesthetics of a shot she was setting up. She claimed to have never witnessed such an atrocity, but photos of her looking on with an expression of horror, and letters from others who were there, prove otherwise. Riefenstahl was never able to cut it as a wartime correspondent; the images of brutality she saw on the front lines in Poland were beyond her control, and thus unbearable to her. It wasn’t that Riefenstahl didn’t know what the Nazis were really up to, or that she disagreed with their actions; she just didn’t want to look at it.

Later, Riefenstahl would bemoan the fact that the war “shattered” her career, as though this was its greatest crime—a prime example of the unabated narcissism that seems to have been her most prominent personality trait. When being interviewed for another documentary well into her 90s, she can barely see in front of her to walk, but she still has strong opinions about how she should be lit and what camera angles should be used. No doubt she also exercised great control over her archives before she died, weeding out the things that she deemed most incriminating and keeping those that she felt put her in the best light. Yet what remains, as we see in Riefenstahl, is more than enough to put to bed any idea that this complex and controversial woman was a mere fellow traveler. She had great artistic ability, but she was also a Nazi, and despite her best efforts, these two things are irrevocably intertwined in her legacy.

Conclusion

Riefenstahl should be the last word on its subject—not just because it is the definitive one, but also because it is the last one we need. She doesn’t deserve any more.

Riefenstahl opens in New York on September 5, 2025 and in Los Angeles on September 12, 2025.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.