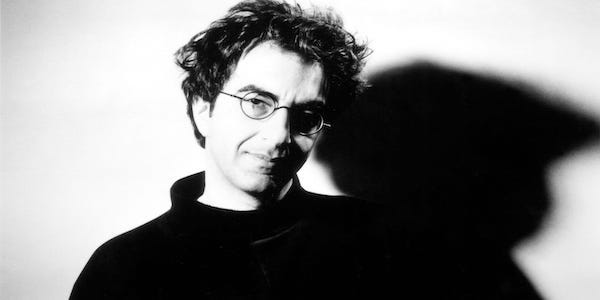

Atom Egoyan’s Celluloid Puzzles

I've been a film lover since being traumatized by "The…

Canadian auteur Atom Egoyan is not as well remembered or highly celebrated as the other independent directors who came up around the same time he did, like David Lynch or David Cronenberg. But the first ten years of his filmmaking career are unmatched by any other director in terms of craft and innovative storytelling. He made a series of dark, off-beat, and simply ingenious thrillers most film lovers have not seen. This is either due to Canadian discrimination or a lack of knowledge of Egoyan’s excellent work.

If last year’s “The Power of the Dog” was an anti-western, for the way it flipped the genre’s conventions and formula, then Egoyan’s movies can be considered anti-thrillers. The premises of his films suggest a story about a web of lies that will play out in a game of cat-and-mouse. American cinemas in the eighties were packed with sexy thrillers, from Adrian Lyne’s “Fatal Attraction” to Brian De Palma’s “Dressed to Kill.” But up in Toronto, Atom Egoyan was innovating a different kind of thriller, one that focused more on twisting the viewer’s preconceived perceptions, analyzing how the media impacts those perceptions and playing nasty mind games on the audience where we wrongly assume the worst of people. Instead of ending with a drawn-out chase or fight scene, Egoyan’s anti-thrillers often concluded in a bitter-sweet reunion, a change of heart, or a shady character finally being shown in an honest light. This is not to say his films aren’t thrilling; they just supply different kinds of thrills, ones more likely to get the wheels in your head turning than your heart pumping.

Born in Egypt in 1960, Egoyan’s family moved to British Columbia when Atom was still a toddler. His identity is deeply rooted in his Canadian upbringing and his Middle Eastern, specifically his Armenian, heritage. He wrote and directed several plays while attending Trinity College, and between 1984 and 1994, he wrote and directed six feature films, in addition to several shorts, TV episodes, and made-for-TV movies.

Egoyan developed an unusual style, one unlike any filmmaker at the time. His films begin with a series of short, seemingly random scenes with no obvious link connecting them. Forget about early exposition dumps, where we learn who all the characters are and what they’re doing; Egoyan leads us into making drastic assumptions about his characters based on trickery.

In his 1994 film, “Exotica,” a man sits in a car with a teenage girl. Based on their conversation we assume she is a prostitute, only to later learn that she is just a babysitter. Only to then learn another twisted secret about why this man hires a babysitter when he has no children. Each scene is one piece of a celluloid jigsaw puzzle, and in the final minutes of his films there is a moment of brilliant clarity, one moment where the final piece of the puzzle falls into place, and every bizarre act we have witnessed suddenly makes sense.

While it takes some filmmakers years and multiple attempts to find their voice, Egoyan hit the ground running with his debut feature, “Next of Kin,” which he shot when he was only 24 years old. Its budget was, in today’s US currency, under 45 thousand dollars. Released in 1984, “Next of Kin” tells the story of an alienated young man, Peter, from a wealthy family who decides to escape his life of privilege. He discovers a family of Armenian immigrants who gave their infant son away when coming to Canada. Peter contacts the family and tells them he is their long-lost son. As we watch Peter dig his way into their lives, we hold our breath waiting for the explosive moment for them to discover the truth. And then, that moment never comes. Peter goes on lying to the immigrant family, his deceit never reaching a tipping point.

Peter is played by Patrick Tierney in what can be described as a near-perfect portrayal of a psychopath that deserves comparison to Anthony Perkins in “Psycho.” Tierney switches from a creeper to a charmer so seamlessly that we almost begin to like him and we even begin to relate to him.

With Egoyan’s genius behind the camera and Tierney’s excellence in front of it, “Next of Kin” should have been an indie smash hit, opening doors for Egoyan much like how “Blood Simple” did for the Coen brothers that same year. But after premiering at the Toronto Film Festival, it never traveled outside of Canada.

Throughout the eighties, Egoyan would release two more films in Canada, both anti-thrillers with the same distinct style and rhythm as “Next of Kin.” They would play in Toronto and at a few film festivals across the globe but never got widespread distribution. Furthermore, both films tackled subject matters decades before they became prevalent in society.

In “Family Viewing” (1987), a teenage boy’s emotionally distant father refuses to visit the boy’s elder grandmother in a nursing home. The family cannot communicate, yet they have bins full of VHS home movies of their old selves smiling and hugging. The boy, Van, then discovers his father is recording over the family videos with footage of him and Van’s stepmother having sex, erasing their happy memories.

In “Speaking Parts” (1989), Egoyan again examines the media’s effect on human behavior and plays with gender roles in the film industry. The plot involves a disturbed loner obsessing over an actor who is sleeping with a screenwriter to get a role in a movie. In Egoyan’s world the loner is female, the stalked actor is male, and the screenwriter abusing their power is female.

All of Egoyan’s early films feature characters obsessively watching the other characters on TV screens. In “Next of Kin,” Peter first sees the immigrant family on a recording of one of their therapy sessions. In “Family Viewing,” Van sits at home and watches hours of home movies of him and his grandmother. And in “Speaking Parts,” Lisa watches film scenes of a background actor on loop. That same actor also happens to be her co-worker, yet she cannot bring herself to talk to him in person. Egoyan shows how during this early era of VHS tapes people began to replace human contact with images on screens.

Egoyan’s 1991 film, “The Adjuster,” was in many ways his first breakthrough, premiering at Cannes and eventually playing in the US. With each film, the scope of Egoyan’s vision grew (as well as their budgets). “The Adjuster” was his first film to feature an ensemble cast of strange and sexually tormented characters, all revolving around an insurance adjuster (played by Egoyan-regular Elias Koteas) who has inappropriate relationships with his female clients.

In 1993, Egoyan returned to his micro-budget, small-concept beginnings and made “Calendar,” which is more of an experimental film than a thriller. It tells the story of a photographer (played by Egoyan) and his girlfriend (played by his real-life wife, Arsinée Khanjian) who travel to Armenia together, where the girlfriend slowly falls in love with their tour guide. The girlfriend and the tour guide speak to each other in Armenian, which the photographer does not understand. Not one line of the Armenian dialogue is subtitled, so most viewers are just as left out of the conversations as the photographer is. In many of Egoyan’s work there is an undercurrent of a kind of foreign entity, a mismatching of cultures. Either the story involves a character being taken out of their natural habitat, or the score consists of duduk flutes. So as we watch scenes set in wintry Canada, with mostly caucasian actors, we hear Middle Eastern music play.

Then in 1994, Egoyan released his magnum opus. “Exotica” is the peak of the Egoyan mountain. Fusing all of the ideas and tropes from his previous work Egoyan creates a masterfully constructed tour de force of cinema, exploring some of the disturbing areas of human behavior disguised as a slick, seductive thriller. In a quietly arresting performance, Bruce Greenwood plays a frequent visitor of a gentlemen’s club who has an intimate relationship and sordid history with a stripper (Mia Kirshner) who dresses in a school girl uniform. The more we learn about these two characters, the more we fall down the Egoyan rabbit hole of deception, trauma, and harmful passion.

His success did not stop there. His seventh feature, “The Sweet Hereafter,” is without question his most well-known. It received raved reviews upon its release in 1997, garnering him two Academy Award nominations, best-adapted screenplay, and best director. For many, it is his masterpiece. In my eyes, it is a slightly watered-down version of his style, his reoccurring themes, and all the things that make Egoyan so great. It makes sense that a toned-down Egoyan film with a more straightforward narrative and less unsettling depiction of tragedy and sexuality would be more accessible to the public. It also deals with tragedy in a more confrontational manner, slightly nudging it into Oscar-bait territory. However, that does not mean it should be his most seen or talked about film when he has so many amazing hidden gems that came before.

Hollywood had finally welcomed Egoyan with open arms, but unlike most directors who get a foot in the door, Egoyan did not make the transition from arthouse to mainstream. He stayed in Canada and continued to make his films his way. However, for many Egoyan fans, “The Sweet Hereafter” also marked the beginning of the end.

His later films are not directed with the same precision as “Next of Kin.” Their scripts don’t push the same boundaries as “Speaking Parts” or “Exotica.” And they rarely feature his signature mind-bending puzzles. Egoyan began directing scripts he did not write, resulting in some movies having nothing in common with his early work. Oddly enough, the more money he was given to make a movie, the worse his films looked. This is not to say all of his post-“The Sweet Hereafter” films are negligible. His 2015 indie, “Remember,” starring Christopher Plummer, is a compelling drama about a Nazi hunter with one of the best twist endings of the last decade.

But Egoyan’s first six features were where he truly shined. One can see how their observations and critiques of media, woven into dark fables about sex and violence, paved the way for other great auteurs like Michael Haneke.

In a film industry where it is getting increasingly more difficult to finance a movie with no major stars attached, we are getting indies with smaller concepts and smaller ambitions. The term “micro-budget” is almost becoming standard. These are tough times, but we’ve seen tougher. Egoyan showed what can be achieved with little resources, that great cinema has more to do with talent and brains than money.

Many of Egoyan’s early works can be found streaming on Kanopy and on the Criterion Channel.

What do you think of Atom Egoyan’s work? Do you have a favorite? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

I've been a film lover since being traumatized by "The Shining" at age six. I graduated from Temple Film School and live in Boston now. I am interested in director-driven cinema and exposing the public to lesser known auteurs. I also do private script coverage.