BAIT: Violence & Class Solidarity In A Cornish Fishing Village

Rose is a freelance film critic who has written for…

Mark Jenkin‘s inventive and haunting new film Bait, set in a idyllic Cornish fishing village invaded by gentrification and middle-class Londoners, explores class solidarity and its reactions to violence in an unique film that expertly skewers the class divisions that play out in modern British society on microcosmic level.There are clear divisions sewn between those living in the village, whose livelihoods revolve around the industries present in their small town, who are slowly becoming priced out of their family homes, their traditional jobs and their own spaces. Meanwhile the middle-class hordes that arrive hold them at arms length – either as oddballs, backward locals, or objects of desire.

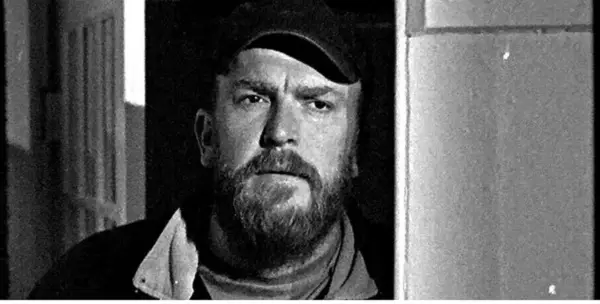

Martin (Edward Rowe) has been stranded upon the land, after his brother Stephen (Giles King) repurposed the family’s fishing boat into a tourist attraction, taking groups of tourists on trips around the scenic Cornish coastline. Desperate to get his boat back, and hostile to the middle-class userpers who have priced him and his family out their family home, up the estate above the harbour, Martin and his nephew Neil (Isaac Woodvine) drag their nets across the beaches in the hope of catching a decent haul. Meanwhile, Neil’s relationship with the daughter of the family who have moved into their family home, Katie Leigh (Georgia Ellery) begins to blossom, much to the disgust of her stuck-up brother Hugo (Jowan Jacobs).

Working-Class Solidarity in the Face of Gentrification

There is a sense of community among the villagers, an unspoken bond that is gradually tested by the changing demographic of their village. Martin, stranded and isolated, attempts to make some money from the fish he catches on the beach – without little success. The few fish he does manage to snare are sold at a steal to the local landlady to sell on to the tourists at the extortionated rates they are willing to pay. The landlady comments that he’ll never be able to get his boat back if he continues to subsidise his catches so generously, but for Martin the monetary value of the fish is not his main concern. He sees this as a requirement for being part of the village community – helping others to keep their own businesses profitable despite the cost to himself.

Despite Martin’s own attempts at maintaining the relationships between the original working class community, this solidarity has begun to break down in the face of the economic violence of gentrification – something which he bitterly fights against, distancing himself from those he feels have betrayed their heritage and principles that he himself tries hard to uphold. The local pub begins to cater more towards the tourists now, closing during the quieter winter months, robbing the villagers of their traditional communal meeting place, their leisure, as it is less profitable and therefore non-essential. His own brother transforming the family’s fishing boat into a tourist attraction is the most painful betrayal. Not only has it robbed Martin of his source of income, it is also an explicit embrace of the tourists that now overun the village.

The Generation Game

As entrenched as Martin is in his attitudes towards the intruders and those who chose to enable them, some of the younger generation do not seem to struggle with these beliefs in the same way, and there is more mixing between the children of the village and those from the London middle-classes.

Neil Ward, Martin’s nephew who helps him spread nets on the beach and shares similar views on the onslaught of tourists as he does, begins a relationship with Katie Leigh, who seems to disregard the divisions that surround them. Getting a rise out of her snobbish brother Hugo appears to be at least a small contributing factor in their relationship, combined with the excitement of a fling without any significant consequences on the rest of her life.

Jenkin does indicate that there is a growing tenderness between them in the final act of the film. While her parents enjoy a staid and silent meal in the darkness of their property, Neil and Katie cook together in Neil’s small kitchen in the estate above the harbour where they have been forcefully relocated to. It isn’t as impressive as freshly caught seafood, but as Neil carefully boils pasta and heats up tomato sauce, there is a peaceful intimacy between them that is sharply contrasted with the evening meal shared by Katie’s parents. In the cottage, silence dominates the space as Tim and Sandra Leigh (Simon Shepherd and Mary Woodvine respectively) avoid eye contact over an evening meal of lobster. While Katie and Neil do not pretend to be, or even aim towards being, in a steady relationship, there is a potential for friendship to be tentatively made across class boundaries.

Violent Outbursts and Differing Reactions

Perhaps Jenkin’s most telling indication that class and privilege will always overrule any sense of community or tentative relationship is in Bait‘s depiction of violence and the vastly different consequences that the perpetrators face.

Martin’s standoff with the Leigh’s erupts one night as he confronts them about the clamp that has been put on the wheel of his car in front of their house. While they maintain that the road counts as their property, Martin argues back that it is part of the habour and no-one has the right to claim it. As Martin begins to square up to Tim, the local barmaid Wenna (Chloe Endean, a true gem and all-round excellent actress in this film of strong performances) joins his fight, shouting back and eventually headbutts Tim in the face and giving him a bloody nose before running off into the darkness.

The Leigh couple retaliate by calling the police, and Wenna is carted off in the middle of the night to a police station miles away without any support, and when she gets back via taxi the next morning, the £100 fare falls to Martin to pay, as she knows her family would be unable to pay. Not only do the middle-classes in the village reactly strongly to violence against them, they also reinforce the economic violence that is perpetrated against the working class community.

The most shocking act of violence however, is not a simply headbutt in an argument that got out of hand, but takes place on the habour in the early hours of the morning. In a fit of rage that his sister is outwardly flaunting her relationship with Neil without a second thought, Hugo confronts them both as they emerged from the fishing shed with tousled hair, Katie wrapped in a blanket instead of clothes.

This confrontation quickly escalates, and Hugo forcefully pushes Neil backwards, away from him, and towards the edge of the harbour. Before anyone can help, Neil falls back, landing on the deck of the boat moored below. He lies, motionless, blood stark against the deck of the boat, enhanced by Jenkin’s black and white photography.

For a family who called the police so readily on Wenna, the Leigh’s reaction is not to show the same decisiveness against their son’s role in the murder of a young man. Here class solidarity and maintaining status are more important that justice, and soon the tourist cottages are abandoned with doors left open in the middle-class residents’ haste to distance themselves from the incident.

Bait: Society on Screen

Jenkin’s stunning and memorable debut is one that pokes itself into the uncomfortable spaces between class and solidarity in modern British society. In a world that is increasingly divided, people are able to find a home, a community within their own class that can be complete absent in the rest of the surrounding society. Working-class solidarity is one based on mutual support, the knowledge that for everyone to prosper, shared resources and services are essential. For those in the middle class, their identity is formed in juxtaposition to the residents of the village, with disastrous consequences.

What are you favourite films about class? What did you think of Bait? Let us know in the comments.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Rose is a freelance film critic who has written for Little White Lies, Screen Queens and Film Daze. She loves thrillers, great female characters, Al Pacino, and multilingual cinema.