The Beginner’s Guide: Danny Boyle, Director

Lauren is 20 years old and is a Multimedia Journalism…

Since breaking out with Trainspotting 20 years ago, director Danny Boyle has proven himself to be one of the UK’s most diverse filmmakers. Growing up in Greater Manchester, UK, in a working class Irish Catholic family, Boyle spent eight years as a choir boy and intended to join the Priesthood, deciding against it at the age of 14. He went on to study English and Drama at Bangor University and began his career in theater in the 1980’s.

In 1987 he began work as a producer at BBC Northern Ireland before making his cinematic debut directing Shallow Grave in 1994. Despite his work in TV and theater, Boyle has held a lifelong admiration for cinema and credits Apocalypse Now with beginning his love affair with film. Boyle solidified his status as a national treasure in 2012 when he was artistic director of the London Olympics opening ceremony ‘Isle of Wonder’, after which he declined a knighthood from the Queen.

Whilst many directors become known for their work in a specific genre, Boyle has consistently genre-hopped throughout his career, which features an eclectic mix of eleven films. In spite of this, the director has developed a distinctive visual style and other trademarks that span across most of his work.

Shallow Grave (1994)

Where better to start than with Boyle’s debut, Shallow Grave. Released in 1994, the film stars Ewan McGregor, Kerry Fox and Christopher Eccleston as a trio of flatmates living in Edinburgh. The three find their new flatmate Hugo (Keith Allen) dead in his room alongside drugs and a suitcase of money. They decide to keep the money and bury the body, a decision that proves to have serious consequences for them all.

As far as debuts go, this is strong stuff. Boyle’s theater roots are clear in the acting, with McGregor in particular indulging in an over-the-top style that perfectly suits the films jet-black comic tone. However, the theatrical comparisons end there, with Boyle fulling embracing the hyperactive style of filmmaking so synonymous with his early work.

Shot on a shoestring budget over 30 days, the film became one of the UK’s most commercially successful of the year and paved the way for Boyle to take on Trainspotting. Producer Andrew MacDonald and writer John Hodge were frequent collaborators in Boyle’s early work, contributing to the distinctive style his 1990’s films share. Shallow Grave introduces many elements that have become trademark with the director, in particular his use of music. A fan of electronic music, Boyle generally avoids traditional film scores and instead infuses his work with pop songs and electronica-infused compositions.

Boyle takes minuscule budgets and turns them into an art form, and Shallow Grave is the supreme example. There is a dark, chilling quality running throughout the visuals, with Boyle using light and tracking shots to communicate foreboding. An important and confident debut, Shallow Grave proved to be a taster for what was to come.

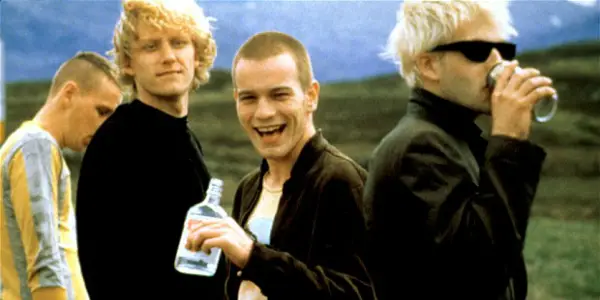

Trainspotting (1996)

Whilst Shallow Grave was successful in the UK, it was Trainspotting that put Boyle on the international cinematic map. Marketed as the British Pulp Fiction, Trainspotting exploded onto the screen in the midst of Cool Britannia and became an instant classic. Telling the story of a group of Edinburgh junkies in the 1980’s, the film takes the essence of Irvine Welsh’s cult novel and comes up with something fresh.

Like Shallow Grave, the film explores friendship under dysfunctional circumstances, and Ewan McGregor delivers one of the best performances of his career as drug-addled Renton, who Boyle described as having the quality that “Michael Caine’s got in Alfie and Malcolm McDowell‘s got in A Clockwork Orange.”

Boyle reunited with Andrew MacDonald and John Hodge for this film and he further hones the style he established with his debut. Again Boyle’s love for electronic and pop music is used to great effect, with the Trainspotting soundtrack becoming one of the best-selling of all time. Iggy Pop’s ‘Lust for Life’ has become synonymous with the film and a generation of disenchanted youth, whilst each song perfectly encapsulates the distorted normality of living with addiction.

The Pulp Fiction comparisons are clear, but Boyle has a distinctive visual style that sets Trainspotting up as a wholly different experience. The violence is minimal, with the characters being more concerned with damaging themselves, and the film is unflinching in its portrayal of drug addiction. Detractors argue that the film glorifies drugs, but Boyle chooses instead to merely depict addiction, leaving it to the viewer to interpret meaning.

Another small budget only accentuates the grungy style of the film, and the gritty beauty of the film lies in the simplicity of Boyle’s shots. Pair that with inspired casting decisions – Boyle insisted on casting Robert Carlyle in the role of psychotic Begbie. Whilst the book version of Begbie was a hulking thug, Carlyle’s slight frame creates a much more sinister incarnation and proves to be one of the highlights of the film.

Trainspotting saw Boyle really hit his stride as a director, paving the way for him to branch out into various different genres following a move to Hollywood.

Sunshine (2007)

Sunshine was a film that saw Boyle fulfill a lifelong ambition of making a sci-fi movie. The film is set in the near future where the sun is dying and earth has been plunged into a solar winter. A crew has been sent into space with a bomb to attempt to reignite the sun in a last ditch attempt to save mankind after a previous mission had failed. Heavily influenced by sci-fi classics 2001: A Space Odyssey and Alien, the film is a must-see entry into Boyle’s filmography.

What’s most interesting about the film is the way Boyle subverts typical cinematic tropes by making light the subject of fear. Audiences are so used to darkness being associated with fear that this use of the sun to invoke the scares is inventive. The influence of Alien is clear with Boyle perfectly encapsulating the sense of claustrophobia that comes with being in space. A controversial tone change two thirds of the way into the film further subverts expectation, whilst the film is also free of any romantic sub-plots and contains very little humour, proving Boyle to be anything but a formulaic filmmaker.

Due to his upbringing, religion has always played a role in Boyle’s work to some extent, but it is with films such as Sunshine that he explores the theme in a deeper way. The film explores religion through employing the sun as a colossal, God-like figure and raising questions over humanity ‘playing God’ by attempting to reignite it. Again, Boyle largely leaves it to the viewer to decide their take on the subject – a common theme throughout his work – arguably raising more questions than he ever answers.

At this point in his career Sunshine was the most cinematic of Boyle’s films, with gorgeous set-pieces and a more traditional score, a hybrid of band Underworld and composer John Murphy. Sunshine is a showcase of Boyle’s filmmaking style applied on a larger scale. The space setting allows for some incredible visuals, particularly the interior of the spacecraft, and Boyle infuses more traditional cinematic techniques with his own offbeat style to create an arresting example of modern sci-fi.

Slumdog Millionaire (2008)

If Trainspotting was his breakout, Slumdog Millionaire was the pay-off. Nominated for ten Academy Awards and winning eight, including Best Director, this film shows what the director can do with a bigger budget. Based on the book Q&A by Vikas Swarup, Slumdog Millionaire tells the story of Jamal (Dev Patel), a teenager who has reached the final question of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? and is accused of cheating. He then recounts his life story, explaining how he knew the answers to each question.

Slumdog Millionaire was another change of pace for Boyle after Sunshine, with the film being a homage to Bollywood cinema. The film is perhaps the most conventional of Boyle’s work, with a feel-good romance at the heart of the narrative, but the director still brings his creative flair to the fore. The pulsing score from Indian composer A R Raham provides a perfect backdrop to the uplifting visuals, with Boyle opting for a much warmer colour palette than he usually works with, bathing the film in warm oranges and reds.

The film was met with near universal acclaim, though it garnered a mixed response in India and there is discussion to be had about whether the film is a western interpretation of Indian slums among other issues. That said, the sense of vibrancy and beauty that Boyle brings to the shots strike reminiscent of Bollywood, and the distinctive feel-good factor is no mean feat considering some of the more sensitive subject matters tackled in the narrative.

Slumdog Millionaire is a must-see Boyle film – the most critically adored and, yes, mainstream, it is an example of how the director can embrace different genres and create something fresh and unique.

127 Hours (2010)

Another common theme in Boyle’s work is triumph of the human spirit and the will to survive, and 127 Hours perfectly encapsulates these ideas within its true-life narrative. Telling the story of hiker Aron Ralston, who was trapped in a canyon for over five days after his arm became lodged by a boulder. Boyle again collaborated with Slumdog Millionaire screenwriter Simon Beaufoy to tell the tale, which is based on Ralston’s memoir, to bring the survival tale to the screen.

Yet again, Boyle opted for a challenging project, with Ralston’s story being a difficult one to commit to film considering he spent 127 hours alone in a canyon. Boyle gets creative with his direction to overcome this, using a combination of Ralston’s (James Franco) video diary and hallucinations to communicate the character’s state of mind, as well as allow dialogue. The director tightly controls shots, never alleviating the suffocating sense of claustrophobia Ralston experienced.

Ralston himself has praised the film for its accuracy, with Boyle shooting at the location of the accident and James Franco giving a dedicated performance in a challenging role. A R Raham returned to score the film, drawing further parallels to the uplifting feel of triumph against adversity also touched on in Slumdog Millionaire.

127 Hours is a captivating entry into Boyle’s repertoire, taking ideas explored in his earlier work and applying them to a terrifying real-life situation to create something visually striking and, above all else, inspirational.

Steve Jobs (2015)

The visionary style of Boyle paired with the writing talent of Aaron Sorkin is enough to get any cinephile excited, and with the enigma that is Steve Jobs as the subject matter the film of the same name was always going to be something special. A film of this nature presented Boyle with a unique set of challenges – Jobs is a beloved figure and creating a film about him that doesn’t turn out looking like an extended Apple product placement was going to be difficult, not to mention the fact that audiences have been inundated with material on the entrepreneur since his death in 2011.

Boyle faced the challenges head on and yet again subverted expectations by taking all the material for a biopic and creating something vastly different. In a callback to his theatrical roots, Boyle embraces the three-act structure of Sorkin’s screenplay to create an intense character study of Jobs. Consisting of three 30 minute scenes taking place in the time leading up to three important product launches across 14 years, Boyle makes a film about Steve Jobs that misses out many of the ‘big moments’ that a biopic would typically cover.

As is commonplace in his films, music plays a huge role, and Daniel Pemberton’s score also follows the three act structure, reflecting the circumstances time period each launch is set in and creating an invigorating atmosphere. Boyle uses creative shots to avoid looking like a glorified Apple advertisement, and the film has a distinct theatre-like feel that extends beyond the narrative structure.

Boyle has often looked at flawed characters in his work and Steve Jobs is a prime example, with Michael Fassbender perfectly encapsulating the qualities of Jobs’ character within the context of the narrative. The film wasn’t hugely successful upon its release last year, but this is likely more a reflection of audience fatigue regarding the subject matter as opposed to a reflection of the film itself. Steve Jobs sees Boyle return to his roots and employ theatrical techniques to create an interesting and different portrait of a well-documented public figure.

Other work

A Life Less Ordinary was the third collaboration with Ewan McGregor, John Hodges and Andrew MacDonald and, whilst flawed, it is a fun entry into Boyle’s repertoire that is worth a watch to round out his early work.

The Beach saw Boyle move to Hollywood with Leonardo DiCaprio as his leading man and adapt another cult favorite novel, this time from Alex Garland. 28 Days Later is a foray into horror that provides a new take on the tired zombie genre, whilst Trance is a welcome callback to Boyle’s early work that also shows how far he’s come, all with an incredible soundtrack from Underworld.

Conclusion

There are few filmmakers who can claim to have forayed into such a wide range of genres as Danny Boyle. The director infuses pop culture into his work, creating distinctive, visually striking films which will stick with you long after viewing. Creative collaborations, both on-screen and off, across his work and an eye for the creative give Boyle’s work its own instantly recognisable, fast-paced style.

With common themes such as religion, flawed characters and unconventional or hyper-realistic circumstances evident throughout his work, Boyle is best appreciated when his films are watched chronologically as to provide a visual map of his evolution as a filmmaker, from the hyperactive black comedy of Shallow Grave to the tightly controlled theatrics of Steve Jobs.

What do you think of Danny Boyle? Let us know in the comments section!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lauren is 20 years old and is a Multimedia Journalism student based in Glasgow, Scotland. She is originally from the Shetland Isles and has held a lifelong interest in film, which she documents on her blog apeerieyarn.wordpress.com. She loves Back to the Future and wishes people would stop paying to see Michael Bay movies.