The Beginner’s Guide: Jacques Demy, Director

Tynan loves nagging all his friends to watch classic movies…

It’s given me great joy recently when I read the buzz about La La Land, and not for the reasons that you might expect. It’s not the fact that perhaps the musical as a Hollywood standard is no longer dead – at least for one brief shining moment. It’s not because it’s been nominated for 14 Oscars, an incredible, albeit inconclusive feat. What the film has done is bring a spotlight to the rich tradition of movie musicals – it’s undoubtedly a resurgence of the fantastical and charming productions that we could use now more than ever. Damien Chazelle was taken by that same magic.

Recently in an interview with Vogue, the director made a profound statement on the musical, “It suddenly became what movies were all about to me. It’s the genre that I’m most obsessed with and know the most about. From Fred and Ginger to Gene Kelly to Jacques Demy, it was like I was catching up on lost time. Then I saw Umbrellas of Cherbourg for the first time. It’s my personal favorite. I think it’s the greatest movie ever made. It’s the one I’m always chasing.” And in this roundabout way, I make my way to Jacques Demy, a man who might be underappreciated in modern circles, but champions like Chazelle, through their work will help in bringing him back to the fore, and rightfully so.

Where Jacques Demy Fits

It’s true that Jacques Demy carved out a niche for himself among the French New Wave and the Left Bank auteurs of the 1960s, although he is admittedly easily overshadowed. Like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, he utilized cinematographer Raoul Coutard, who brought gorgeous black-and-white tones to his debut Lola, shortly after the seminal classics Breathless and Shoot the Piano Player.

Furthermore, Demy’s marriage and creative connection to fellow filmmaker Agnes Varda would forever attach him with the Left Bank movement, including visionaries such as Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. However, if you begin to watch Demy’s films, you find someone strikingly different than his contemporaries in so many fascinating ways.

His inspirations could be chocked up to numerous people, but there’s without question the eye for a vibrant palette and impeccable staging of Vincente Minnelli, and maybe a bit of the unabashed affection for fantasy that can be gleaned from the work of fellow Frenchmen Jean Cocteau. But for our purposes, Demy was an heir to the Hollywood musicals of Astaire & Rogers and Gene Kelly.

He took the framework that was already in place with its lavish Technicolor dance routines and song, and subsequently married it with the style and locales of his native France. But put him up against any of his other contemporaries and there’s an accessibility to Demy that feels unprecedented – welcoming to all who dare give him a chance.

His stories are almost always preoccupied with love both joyous and wistful, and the workings of fate within the human existence. He carefully develops a web of relationships crisscrossing with each other and it doesn’t end with just one film, as it carried over through much of his work. What sets his filmography apart is the fact that he developed a type of fantasy reality where his characters exist, all interconnected in a fateful patchwork of a glorified everyday reality.

Lola (1961)

Lola opens with a nod to Max Ophuls, hoping to pay homage to the extravagant pirouettes of the former director’s continuously roving camera. While Demy might not fully succeed in that feat, with Lola he quickly comes into his own, and that’s far more entertaining. It truly sets the groundwork for many of his later works, as he begins to carve out his own unique world of fateful encounters and interconnected characters fittingly located in his boyhood home of Nantes.

Demy himself termed Lola “a musical without music”, and really you could say that of all his subsequent films, whether they utilize music extensively or not. Here he introduces us to two characters who will show up in his later work as well, the titular cabaret singer (Anouk Aimee) and Roland Cassard (Marc Michel), a childhood friend from many years before who drifts back into her life after a chance encounter.

She is biding her time, waiting for her long lost love to return to her. She does her best to take care of her young son, while spending her free moments outside of the club with a friendly sailor looking for some companionship. Meanwhile, while Roland loves her, she concedes that their relationship will never be romantic. He goes off on a voyage wounded and Lola reunites with her lover. But that’s not the last we see of them in the ever-churning world of Demy.

Bay of Angels (1963)

Bay of Angels is Demy’s second film styled with crisp black & white cinematography. At this point, he has not fully realized the vibrant palette that would be synonymous with many of his later films. In fact, this picture is quite different than many of his others.

Still, it weaves together some of his overarching themes, in this case occupying itself with the chance involved with spinning roulette wheels that fill casinos instead of the fateful encounters between characters. In this case, Jean (Claude Mann) is a bank employee who slowly becomes obsessed with gambling, frequenting all the major casinos in Nice and Monte Carlo.

His own preoccupation is only escalated further when he comes in contact with Jackie (Jeanne Moreau), another compulsive gambler. Neither of them can stop, and as luck would have it they also have a bit of a romantic fling. They’re a thoroughly reckless pair, and in the same breath invariably compelling. And they too fit into the world of Demy, seduced by the coaxing of love and chance and infatuated with the sea. For them, the Bay of Angels is a place of good luck, and for Demy his own personal attachment to the sea seems connected not only to his home but his fascination with the very life and vitality that the seaside and ports seem to represent for him.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

There’s no doubt why Damien Chazelle references Umbrellas as his favorite film – the film he is always chasing because, in truth, it’s probably the peak of Demy’s filmography. And perhaps one of the most striking traits that Chazelle pulls from Umbrellas, in particular, is a vivid, music-filled love story that is nevertheless thoroughly grounded in the everyday. That is key.

In Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Demy is once again in a seaside town, this time Cherbourg following the life of a young ingenue named Genevieve (Catherine Deneuve), who helps her mother (Anne Vernon) run their family umbrella shop on a daily basis. Despite their humble means, the naive beauty is thoroughly content when she becomes enraptured with a handsome mechanic named Guy (Nino Castelnuovo).

In truth, Umbrellas of Cherbourg in all of its resplendent beauty functions more as an opera than a typical musical, because the songs are not just a simple act of expression but they serve a practical purpose as well. Thus, in his artistic audacity, Demy allows the whole story to play out in song, even the mundane moments. It ultimately gives the film a cohesive quality that nevertheless cycles through the gamut of emotions, from youthful exuberance and euphoric reverie to the incalculable melancholy of loss. It boasts a lasting resonance that burns like bittersweet coals, aided greatly by Michel Legrand’s own extraordinary masterwork in composition.

This is the film that made not only Catherine Deneuve a star, who still stands as one of France’s imitable icons to this day, but it bolstered the careers of both Demy and Legrand. If this is the film that scholars, critics, and casual viewers use to judge their output, they should all be extremely proud.

The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967)

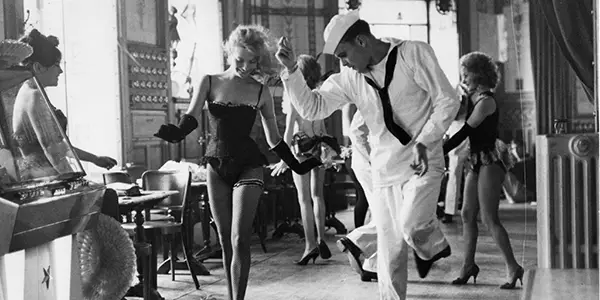

If Umbrellas of Cherbourg is Demy’s heartbreaking foray into operatic romance, then The Young Girls of Rochefort stands as his most unabashed exercise in fantastical Hollywood escapism. If any of his films paid homage to his predecessors in Hollywood including Stanely Donen and Vincente Minnelli, this is the film that shows that adulation most obviously.

The story of two twins Delphine and Solange (portrayed by real-life sisters Catherine Deneuve and Francoise Dorleac), is juxtaposed with the arrival of a group of out of town carnies who make their way into town for a big show. The girls who run a local dance studio in the idyllic seaside town are at the core of Demy’s latest examination of fate, weaving together chance encounters and missed opportunities in another patchwork of romantic tête-à-têtes. His characters drift through the story-line orchestrated, but still somehow free-flowing and unrestrained. The song and dance are in no way separated from the sometimes banal actions of the plot.

Once again Demy and Legrand join forces, this time with choreographer Norman Maen to build another world akin to Cherbourg, where bright tones splash the screen with color and every person delivers their feelings and exposition alike in the mode of song.

But the shining moments in this narrative not only stem from the two sisters’ introduction, singing the catchy collaboration “Chanson des Jumelles,” but also the inclusion of American musical stars, including George Chakiris (of West Side Story fame) and choreographer Grover Paul. Still, what we all really want is Gene Kelly, Mr. Singin’ in the Rain himself, although his work in this film undoubtedly hearkens back most obviously to An American in Paris, if not simply for location then also due to the vibrant pastels and choreographed dreamscapes of the mise-en-scène. However, Demy also calls upon the homegrown talent of the equally estimable Michel Piccoli and Danielle Darrieux to round out an all-star cast.

Model Shop (1969)

Model Shop stands out as a peculiar aside in Demy’s filmography, often passed over for his more remembered productions. In truth, it stemmed from a vacation to Los Angeles, but he was so taken with this city that he was compelled to make a film around it. And that he did.

So once more he took a seaport town, in this case, the L.A. of the Sunset Strip and KRLA Radio, and gave it a bit of the Demy touch – inserting it into the world that he had already created. Lola (Anouk Aimee) drifts back into the narrative as the aloof beauty who fascinates the local George Matthews (Gary Lockwood), a struggling young architect who represents the general malaise of the day. He’s unhappy with his girlfriend, an aspiring actress (Alexandra Hay) and oddly indifferent when he receives his draft notice for Vietnam.

Demy once more develops a type of musical, using diegetic car radio tunes as well as a score by local L.A. rockers Spirit for a meandering vignette-driven film, in some ways foretelling of American Graffiti. In fact, there is some proof that Agnes Varda ran a screen test for her husband’s film with an unknown Harrison Ford, though the casting fell through. No matter, Model Shop is a surprisingly lucid time capsule, and although it lives in relative obscurity, it still ties in beautifully with the rest of Demy’s oeuvre, both thematically and overtly through numerous callbacks to his earlier works.

Donkey Skin (1970)

At the apex of his creativity, Jacques Demy took fantasy and entrenched it deeply in reality. But Donkey Skin is a striking example of how he took his now fully realized aesthetic and translated it to a fully immersive fairy tale. It’s undoubtedly his closest approximation of the work of his predecessor Jean Cocteau, most obviously La belle et la bête (1946).

Aside from the normal fairy tale staples, from fairy godmothers and love struck princes to lowly maidens elevated to royalty, Donkey Skin boasts the childlike reverence and simple special effects that blessed the former’s work. And of course, the most obvious homage comes with the casting of the legendary Jean Marais as the King, an actor best remembered for his work in Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast and then Orpheus as well. And yet again Demy partnered with Michel Legrand, whose score once more dances between gaiety and somberness to guide the oscillations of the story’s trajectory.

There’s an unquestionable care taken in telling this fairy tale story, as Catherine Deneuve paired with her favorite director goes from opulent princess to lowly “Donkey Skin” fleeing an incestuous marriage with her father the King. However, like Beauty and the Beast as well as Cinderella, she goes through the apotheosis of becoming a princess when the Prince’s ring fits perfectly on her finger. Returning to these themes again and again, Demy allows her ignominy and wistful longing to be replaced with passionate romance. A happily-ever-after ending as only Demy could deliver.

Une Chambre En Ville (1982)

It’s fitting that the last film on this list was also shot on location in Nantes, where Demy began with Lola. And it makes complete sense in coming full circle, as there is a familiarity and a connection to his hometown that imbues Une chambre en ville with a certain intimacy.

While a lesser work and perhaps not on par with the likes of Cherbourg or Rochefort, Une chambre en ville is still another stunning offering from Demy, for various reasons. Once again, as he often so boldly chose to do, the dialogue throughout the entire film is sung, with the plot set against the backdrop of a worker’s strike in 1955. Recalling the romantic despair of Umbrellas of Cherbourg, this story takes particular interest in the class divide.

In its most striking set piece, Demy avows to allow an entire riot scene to play out through song, and the results are surprisingly haunting as the opposing forces of workers and riot cops clash. The final notes in a tragic tale that could never be, and perhaps it’s a fitting place to leave Demy for now.

Conclusion

Though his career had many high points, it was also riddled with struggles to the end. Demy is often written off in deference to his more vocal or “revolutionary” contemporaries like Jean-Luc Goddard and François Truffaut. But hopefully, the works of Jacques Demy can return once again to the center of the public consciousness, because his films have so much to offer us in all walks of life – especially now. They can be wistful in one moment or overcome with joyful elation in another, developing a nuanced tone that is surprisingly resonant today.

Listen to Damien Chazelle and go search out Umbrellas of Cherbourg if you have not already. Allow yourself to be whisked away by the magical, fantastical, vividly romantic reveries of Jacques Demy.

Have you heard of Jacques Demy before or any of his films? If so, do you think he’s an underrated director?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Tynan loves nagging all his friends to watch classic movies with him. Follow his frequent musings at Film Inquiry and on his blog 4 Star Films. Soli Deo Gloria.