Why Cinema’s Response To The Streaming Revolution Is Doomed To Failure

Jim (Twitter: @JimGR) has written about film since 2010, and…

If cinema is to survive as anything resembling what we recognise it as today – and I believe that is worth preserving – then major theatrical exhibitors need to stop pissing into the howling gale that is the streaming revolution. Making that metaphor manifest by spraying water into the faces of 4DX audiences won’t secure that future.

Since Roma triumphed in some key categories at the Oscars, including the cornerstone craft of cinematography, the ongoing debate about the status of films developed or distributed by Netflix has been dialed up. The debate isn’t new: it’s well over a year since Cannes changed its eligibility rules in time for the 2018 edition in response to controversy around Okja and The Meyerwitz Stories, Netflix-only affairs outside the 2017 festival.

Since then, Icarus won a statuette at the 90th Oscars in 2018, and Period. End of Sentence won documentary short this year. However, the increasing amounts of money being thrown around – Netflix are set to spend over $15Bn on original content this year – have put the future of cinema into sharper and more urgent focus than before.

The Cinema ‘Experience’ & The Green Book Red Herring

The extreme opinions of the debate (also the most loudly expressed, as often seems to be the case) are, on the one hand, that those denigrating the ‘cinematic’ qualities of streaming-focused releases are simply not moving with the times and, on the other hand, that cinema is being taken over by glorified TV movies. Steven Spielberg has stated that streaming releases would be more than worthy of Emmys, but not Oscars, and has received plenty of flak as a result (the ‘Old Man Yells at Cloud’ meme has been given a good workout by online commenters).

Let’s put aside the contestable nature of what film deserved industry awards. The victory of Green Book nicely highlights the need to do this: for all its amiable performance-led charm, undermined by patronisingly racist moral themes, there is nothing particularly spectacular about the film. The idea that Green Book is inherently more cinematic than Roma by virtue of the primary release format is patently absurd, and serves to illustrate that films should be considered on their own merits, not that of its distributor.

Although defending the theatrical setting is a worthwhile endeavour, the necessity of it has slowly been eroded, and the primary culprits are theatres themselves. A staunch defence of the status quo ignores the fact that the term ‘cinematic’ has ceased to be meaningful by the actions of the very companies whose bottom line now depends upon it. Lack of care in the presentation of films, for many years now, has manifested in a lack of respect for that presentation from audiences. The reasons are manifold: lack of skilled work for projectionists, meaning that projection errors go unnoticed or unactioned; increasingly long adverts pre-roll (in both multiplexes and independents); rising and unpredictable ticket pricing; high prices at the concession stand; out of focus pictures; no masking at best, and incorrect masking at worst; and homogenised offerings of blockbusters thousands of times a day.

The ‘picture palace’ concept died some time ago. Beautiful and unique cinemas are still present the world over, but the majority of filmgoers pile into multiplexes. This needn’t be a dreadful thing, but given that many operate on autopilot from a projection standpoint, filmgoers are increasingly aware of the resulting conveyor-belt feel. In addition, a lack of variety in the films offered has degraded the cinematic experience even as ticket prices have risen. Since adverts roll for an age, folk try and judge when the film will actually begin and eventually come in with phone torches glaring. Lack of consistent masking means that films are produced and projected in aspect ratios that don’t require it, or the screen is merely treated as a giant television with its aspect ratio changed. When obvious visual boundaries in ‘letterboxed’ views are removed, this contributes greatly to an ‘immersive’ feeling (and, indeed, was the point of Cinemascope when it rose to prominence), and many films can be subtly affected by this.

Audience Behaviour

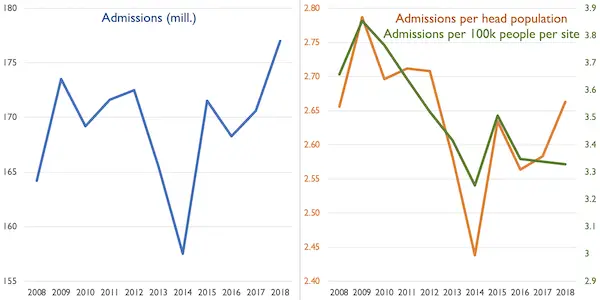

It’s often reported that audience numbers are on the up in UK cinemas. However, the question has to be asked: who is going, and what are they going to see? In the period 2008-2018, admissions numbers rose approximately 8% over that period, albeit with some ups and downs (with higher numbers recorded in years with landmark releases such as The Avengers, Skyfall or Star Wars: The Force Awakens). However, over the same period the UK population itself grew by nearly 7%, the number of screening sites by 7% also, and total screens by a whopping 21%. A strong argument can be made that the rises in admissions seen are not an organic result of the silver screen’s magnetism.

If we fit a linear trend through box-office admissions (in an attempt to smooth out the bumps) the rise is a much more conservative 0.4% per year over the whole period. Even if an anomalously low 2014 is discounted (Paddington the comparatively restrained top earner in the UK that year), the trend is a mere 0.5% growth per year. If a derivative quantity of admissions per head of population is calculated, then growth has been flat at best, slightly declining at worst. If it is further normalised for number of screening sites, then there is a definite decrease of over 9% over the period, or a decline of nearly 1% year on year.

In a shorter period, Netflix has raced from a standing start in the UK to well over 8 million subscribers. The comparison isn’t perfect, but there is no way of presenting the numbers that would improve the view from theatre chains standpoint. Multiple people (and certainly families) often share streaming accounts, so there is not a one-to-one equivalence against potential cinema tickets. This also doesn’t address other streaming services, such as NOW TV and Amazon in the UK, Hulu and Amazon in the USA – where there will not always be overlap with the Netflix customer base – and newer emerging services such as the Criterion Channel, the forthcoming Apple streaming service and Disney+, and more niche services such as Curzon Home Cinema and MUBI. With over 80 original films – in addition to new and continuing serials – released on Netflix in 2018, it’s easy to see why 58% of subscribers rated cost-effectiveness as the reason for signing up in a recent survey.

When most cinemagoers cite ticket prices as the primary deterrent, theatres are clearly losing the battle in terms of cost. When streaming services start to offer comparable quality content on average, attempts to shut them out of the sphere smack of economic protectionism. Admittedly, the primary objective of the streaming firms will be to acquire subscribers, not exhibit cinema. However, if theatres (and the less progressive-sounding pillars of the filmmaking community, such as Spielberg) can find a way to work with these firms rather than automatically move to shut them out, then both can benefit.

Cinematic Protectionism & Unintended Consequences

When handled correctly, the theatre is worth preserving. But even if these aspects are addressed, the long-term business angle must evolve in order to allow for positive change. The recent decision by Picturehouses in the UK to require a long theatrical window for its releases is a good example of the puzzling approach some chains are taking in response to streaming. Requiring an exclusive theatrical window of 16 weeks, in one fell swoop the requirement rules out a number of films released by Curzon Artifical Eye simulataneously on streaming and in cinemas. Many of these would be perfect fits for the Picturehouse audience – Loro, The Souvenir, At Eternity’s Gate, to name just a handful – and brings the chain into line with overlord business Cineworld PLC. More stupidly, however, audience-going numbers – often presented with a rose-tinted reporting angle discussed earlier – don’t back up the decision to go this route. The streaming revolution may feel like it has been around for a while, but we are barely at the start of the wave, and these companies risk being washed away.

Up until now the primary response to declining audience enthusiasm has been to differentiate on experience, rather than content. As discussed above, however, the old-school basics of cinematic exhibition have been neglected. Even if these problems admittedly go unnoticed by many cinemagoers, it would undoubtedly improve everyone’s theatrical experience were they rectified. Instead of putting effort into the fundamental art of screening, cinemas have sought to differentiate themselves through glorified gimmicks, or by screening non-cinema content such as theatre or opera productions, live music events, or – in an enormous irony – TV series finales. The appeal of 4DX and similar technologies seems minimal at best, amounting to not much more than the old Universal theme park rides.

Worrying about where your possessions are as you get buffeted around during Aquaman is not conducive to a fun or immersive experience. The enduring presence of 3D can be explained by the ease of post-conversion, increased entry-fees, and sunk-cost investment made in 3D screens, rather than anything to do with improved audience experience (since the release of Avatar, the percentage of screens equipped for digital 3D in the UK has increased from 2% to 48%, while the number of productions filmed natively in 3D is minuscule). Focusing on 3D offerings, whilst also offering patchy accessibility for the vision or hearing-impaired, simply means more audience segments easily driven to the couch. Theatre operators are fiddling while Rome burns.

Given the larger audiences, larger budgets, and apparently wider distribution offered by streaming services, it is highly likely that filmmakers and producers will start to focus on the creation of content more suited to the popular format, at the expense of ‘traditional’ cinema. This is the worst possible scenario, but it is a real possibility.

The average home setting, of course, detracts from the overall film-viewing experience in countless ways: it is much more limited in terms of equipment, and more distracting in terms of attention. Home viewers will naturally favour more easily consumed material, content that doesn’t require the same level of disengagement from our immediate environment. If that shift starts to be made on a fundamental cultural level, and the exhibition advantage of theatres is reduced, then truly there is no way for cinemas to ‘win’. Viewers don’t win, either.

In a way, the current industry response – from some cinema chains and some festivals, such as Cannes – can be equated with the economic policy of protectionism. In the same way that states often place barriers to cheap imports in order to protect domestic industries, so have theatres and the wider filmmaking world begun implementing the barriers mentioned above to streaming-focused production houses. Protectionism has its supporters and opponents, but one thing is very clear: if you’re protecting a busted flush, then you are doomed to failure. Furthermore, the recent successes of streaming productions on a critical level mean we are not dealing with something analogous to a cheap plastic imitation of the ‘real’ product.

The Way Forward

Cinema exhibition as we know it must evolve or die. There are small schemes already in place that could demonstrate something akin to the way forward. MUBI, for instance, allows subscribers to see one specific film in theatres for free every week as part of the subscription. This isn’t much use if there isn’t a showing nearby, but it does offer a continued theatrical opportunity (Under The Silver Lake was distributed by MUBI in the UK, and also offered under this ticket scheme), and something that could be adopted by streaming houses with cooperation from theatre chains.

A number of cinema luminaries – from Paul Schrader to Sean Baker – have offered other ideas, but only the bean counters at streaming giants and theatre chains know what would work. However, with the number of MBAs inside the corporate HQs and the opportunities for kudos and cash on all sides, it seems impossible that there isn’t a solution – or many – out there.

Cinema is an art form that should be celebrated in all its guises, and only by evolving and redefining its cornerstone adjective – cinematic – along the lines of the content itself rather than the delivery method can that be done. At its best, the cinema is a space for people of varied backgrounds, tastes and lives to share a cultural experience. As the most popular artform it arguably has a responsibility to present that artform in the best way possible. Whether that involves soda or wine, popcorn or risotto, reclining chairs or deckchairs is down to the individual theatres and chains and local preferences.

What should be common, however, is an inclusive space that shows a fundamental and unwavering respect for what it shows audiences, regardless of whether the distributor’s business model is based on the silver or small screen.

Do you agree that the cinema business needs to evolve and work with streaming services, or will it weather the storm by battening down the hatches?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Jim (Twitter: @JimGR) has written about film since 2010, and is a co-founder of TAKE ONE Magazine. His written bylines beyond TAKE ONE and Film Inquiry include Little White Lies, Cultured Vultures and Vague Visages. From 2011-2014 he was a regular co-host of Cambridge 105FM's film review show. Since moving back to Edinburgh he is a regular review and debate contributor on EH-FM radio's Cinetopia film show. He has worked on the submissions panel at Cambridge Film Festival and Edinburgh Short Film Festival, hosted Q&As there and at Edinburgh's Africa In Motion, and is a former Deputy Director of Cambridge African Film Festival. He is Scottish, which you would easily guess from his accent.