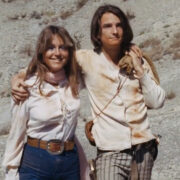

Interview with Lauris and Raitis Ābele for DOG OF GOD

Payton McCarty-Simas is a freelance writer and artist based in…

Brothers Lauris and Raitis Ābele play with reality in their latest feature, Dog of God, a rotoscoped historical tale of abject medieval monstrosity. In the desolate village of Laube, an ancient shamanic werewolf may or may not have joined their midst, just as a hypocritical pastor starts a witch hunt against the beautiful local innkeeper and herbalist. Spiritual — not to mention sexual and psychedelic — chaos ensues. To celebrate this trippy film’s debut at Tribeca this year, Film Inquiry sat down with the brothers to discuss their inspirations.

There are so many awesome disparate elements going on in this movie — werewolves, witches, the psychedelic angle. What was the core idea that inspired the rest?

Raitis Ābele: Okay, the core was a werewolf trial, because it’s based on an actual event that took place in 1692, the 17th century. It’s the most famous werewolf trial in Northern Europe because it’s very well documented — what the priest said, what the judge said, what the werewolf said. It’s all written down, transcripted. We know this story. Then the [co-]screenwriter [Ivo Briedis] wrote a script based on this trial, but it was for a narrative film. So when we decided to go into animation, together with animator Harijs Grundmanis, we added a lot of elements, though the core stays the same. So yeah, the werewolf was central. Now, if you look at the film, maybe the werewolf is not the central part anymore.

Lauris Ābele: But also, where we live, we have a — I don’t want to compare precisely, but let’s say, like, we’re here in New York, Manhattan, so it’s like upstate New York. We have a river called the Daugava, and it was a place where the witches were drawn. So in a Hollywood style, it would be, is it a witchcraft movie? Is it a werewolf movie? But back in the day, it was all the church against all the superstitions. Then there’s the Inquisition, and right during the period where our movie takes place, that’s when Swedish law forbade Inquisitions. So one of the theories [about this famous trial], is that this werewolf was maybe a bit of a trickster during the trial, that he knew that he was not going to be tortured.

RA: So in a way nobody knows. Historians are doubting. Was he a trickster who knew the laws and just made fun of the church? Or was he really some pagan shaman entity that told the truth — what was at least his truth, right?

That’s so cool! So did you do a lot of broader research into the period? What were you reading to prepare for this beyond the transcript from the actual trial?

RA: We did a documentary reenactment [in 2018] called Baltic Tribes: Last Pagans of Europe, and it was about the 13th century. So there we read a lot during that time, and moving to 17th was not so hard anymore. But then academically, there are two books. One that particularly inspired my brother is by Adam Douglas. He has a book, The Beast Within. I spotted it in The Strand in 2010 here in New York, and there I read about Livonian werewolves. I thought, “Oh, he’s writing about like our werewolves. That’s cool.”

LA: Ivo Briedis [the co-screenwriter] had already done most of the research. But if someone is interested in werewolves, there’s a particularly new book called Old Thiess, a Livonian Werewolf by American anthropologist Bruce Lincoln and an Italian Carlo Ginsburg. And it’s a super interesting read about the whole phenomenon. And when you read that book, same as Adam Douglas’ book, there’s kind of a weird feeling that our werewolf story means more, even somewhere else. For some historians, it’s a puzzle. So it’s an academic discussion regarding the Pan-European shamanic world, the pre-Christian worldview. It’s an interesting read.

RA: And then there was one other specific book that we used, but I think for English-reading audiences it’s not available. I think it’s just in Latvian. It’s a book of spells. A guy in the early 20th century, he collected spells from old people and stories from old people in rural neighborhoods. It’s an academic book, but when you read it, it’s something like a Black Book. People don’t want to keep that book at home — one of our friends is a professor of mythology and he said, “I have it at home, but I keep it near the Bible.”

That’s awesome. So earlier you said the concept came first, and you eventually decided to switch to animation. What was it about this story that inspired this particular style of animation?

LA: We wanted to do a live-action film. We applied for funding, and it would have been way different. And then Raitis was working on the development stage of Flow [last year’s winner for Best Animated Feature at the Oscars, the first Latvian film to do so] ….

RA: I was working with them, and I was there for one year. I was just in an environment of animation. Testing out new tools, that was just part of my daily life. So then I came back to Lauris and said, “Hey, let’s do it in animation,” and Lauris was not keen in the beginning ….

LA: Because, yeah, I somehow was in this cliche that animation cannot be serious, but it’s very good that it cannot be serious. It gave us a lot of artistic liberty.

Totally, and you’ve done such a good job translating this story to that style. It’s so surreal. Which brings me to my next question: the psychedelia in this film. I know that’s really central to witchcraft lore, but was that an element that sprung from the werewolf side here? Where did it come from?

LA: There’s a theory behind, as you mentioned, the witchcraft, witches riding on brooms. There are anthropological theories there that that was probably part of some ritual which involved some mind-opening substances. So we wanted to put that shamanic experience in also. It was our intention not to do the classic Hollywood franchise werewolf movie, but to bring this. And if people are surprised, we’re okay with that. We did our jobs. We’re trying to bring our werewolves, shamanic witchcraft, and some psychedelic experience to the story.

RA: Also, our werewolf, what he says in his trial is that he goes to Hell, and he can only become a wolf three times a year on specific nights. So probably that’s on ritual nights where something is consumed. We have a lot of fly agaric mushrooms [those classic red and white psychedelic mushrooms] growing in forests [in Latvia]. That shamanic culture, it’s not preserved any more in Latvia, but our neighbor country Lithuania, they still have folk healing traditions and use it as a medicine.

LA: They have a specific name for a person called mushroom eater.

That’s fascinating. I want to pivot a little bit to talk about the score, which I just loved. It’s so appropriate and fun, and there are so many different varied themes within it that I enjoyed a lot. Can you talk to me about your process making that score?

LA: Thank you for that. The main idea was to channel the feeling of our childhood movies, mostly in the ’80s and ’90s. They’re all synth driven — synth pop, synth rock. We wanted to have a bit of, with all due respect, a Vangelis feeling, as he played with digital instruments, which gives freedom. Also we play in a psychedelic metal band. So we like bands like Neurosis and Swans. So the idea was to play one chord, but play it like it means something. And then also we wanted to put some spiritual shamanic experiences in there too. So it was a super eclectic and weird combination that might have been hard for a composer. To describe all our influences for this movie might have been too weird. Because we’re in Latvia, we have good musicians, good film score companies. But for this, it was specific that it needed to be digital, to have this feeling of an ’80s blockbuster movie.

RA: We didn’t want to use folk instruments as this kind of a period piece might normally require. At one point, Lauris said, “Now it’s easier for me to compose the music than to explain everything to another composer.”

Are there any movies that you drew inspiration from, or movies that you think are similar for people who like yours and want to explore this style more?

LA: Yeah, I’d say Rainer Sarnet, the Estonian director, has a film named November. It’s a black and white movie. It’s beautiful, and it’s the same [mythological] world as our movie. And then I would say Ralph Bakshi animations, Heavy Traffic, Fire and Ice. Then the latest, there’s a new rotoscope movie, not by Ralph Bakshi, but also he drew inspiration from him. It’s called The Spine of the Night.

We want to thank Lauris and Raitis Ābele for speaking with us.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Payton McCarty-Simas is a freelance writer and artist based in New York City. They grew up in Massachusetts devouring Stephen King novels, Edgar Allan Poe stories, and Scooby Doo on VHS. Payton holds a masters degree in film and media studies from Columbia University and her work focuses on horror film, psychedelia, and the occult in particular. Their first book, One Step Short of Crazy: National Treasure and the Landscape of American Conspiracy Culture, is due for release in November.