MORE THAN A WORD: Generation With A Vision

Brian Walter is a college professor by day and a…

Disclosure: This past spring (in cautious hopes that it would prove even half as good as it has, in fact, turned out to be), the reviewer purchased a t-shirt to support the production of this documentary.

Early in the famous tragedy that Shakespeare named (in part) for her, young Juliet Capulet bemoans the superficial and seemingly arbitrary label that would keep her from her new crush. “What’s in a name,” the heroine of Romeo and Juliet famously asks, when “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet”?

Poor child. As she and her charming but equally doomed young Montague boyfriend will eventually learn, the contentious forces of European tribalism have always invested an awful lot of confining power — however artificial, however needlessly destructive — in our naming conventions.

John and Kenn Little, the brothers who directed the new documentary More than a Word, repurpose Juliet’s charmingly innocent question to address a much more historically expansive and urgent problem. What happens when we unpack the American custom of naming sports teams for the Native inhabitants of this continent? What does it mean to reduce our fellow human beings to the status of mascots? The answers served up by this perceptive, restrained, and subtly artful film put Juliet’s famously twitterpated musings to shame.

More Than a Word focuses most intently on the long-running legal battles to remove the dictionary-defined racist slur ‘r—skin’ from the National Football League’s Washington franchise. But, more deeply and ambitiously, the filmmakers illuminate the power of language to shape attitudes and thus — finally, inevitably — to inform action. If it remains true, after all these centuries, that the pen is mightier than the sword, then it is still more sadly and even disgracefully true that the mightiest pens in our nation have all too often weaponized themselves with the sword of racial stereotyping.

And now, when the 2016 election has seemingly swung the culture war pendulum so forcefully to the right, licensing previously self-marginalized Confederate-flag wavers to push so brazenly to overturn the hard-earned civil rights gains of the last century, this film’s goals can seem all the more quixotic. How many people in Trump’s desperately, divisively echo-chambered America will even hear of this film? And, of those, how many will dismiss More Than a Word out of hand with the thoughtless, useless smear-label of ‘political correctness’?

Fortunately, the Brothers Little clearly understand the dangers of our increasingly rancorous political climate. And thanks to their careful, often very subtle work, anyone with an even slightly open mind who watches More Than a Word will likely forswear the ‘r—skin’ slur as decisively as most of us long ago forswore the equally hateful, shameful ’n-word’ slur.

But whatever power it might have to win over reasonably open hearts and minds, More Than a Word works all the more laudably to fortify a sense of community around the clear vision of those who have been fighting this good fight for so long and against such steeply monied odds. This is a lovely, heartening testament of a film for any of us who can’t quite give over the faint, wishful hope that — somehow, some way — the truth will finally prevail.

Writing ‘History’

The crucial work of reframing the conversation around racist mascot names begins in the film’s inspired opening segment. A vintage television set (all knobs, dials, and rabbit-ears) slowly looms larger and larger against a stark white background, the screen supplied with black-and-white clips of a 1933 educational film purporting to offer the ‘true story of the American Indian,’ the ‘strange and unusual’ figure who has ‘been painted as permanent adornment on the walls of our public buildings, homes, and art galleries.’ The narrator’s voice is (of course) recognizably male and white, deep, deliberate, and — for any of us raised on this continent over the last century and more — unwarrantedly authoritative.

This ingenious opening figure of More Than a Word reminds us, right from the start, that history is written by the ‘winners.’ And in this case, the WASP ‘winners’ have insistently centered and glorified themselves within this narrator’s ‘royal We,’ enlarging the myths of our European ancestors’ conquests to such enormous proportions that all others’ stories are crowded out of the ‘historical record’ by our (fantasy but unquestioned) white magnificence. The native inhabitants of this continent (known as Turtle Island long before Declaration of Independence author Thomas Jefferson was even born) are little more than curious decorations for “our” automatically august structures.

In a mere 45 seconds, then, our directors have cleverly undone centuries of colonial erasure, offering their film up as a palimpsest of deeper truths about the fuller, richer story of human life in our ‘Western Hemisphere.’ These are the real stakes of racist mascot names: who gets to tell the story of human life on this landmass? The aggressive, Johnny-come-lately settlers from Europe, or the descendants of the human cultures and civilizations that have inhabited Turtle Island for untold ages before those Europeans absurdly agreed among themselves to call it the ‘New World’?

Acknowledging the Opposition

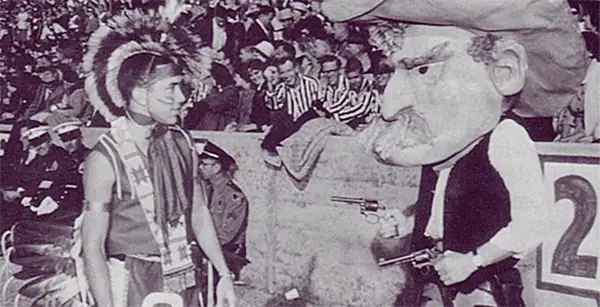

Fortunately, the Brothers Little are far too smart and disciplined to make the answer to this question a simple either-or proposition. They give plenty of screen-time in More Than a Word to supporters of the ‘R—skins’ team name, treating them with simple but unmistakable respect, no matter how little persuasive weight their broadsides tend to carry. From Washington football fans gotten up in faux headdresses and ‘warpaint’ to blithely well-poisoning Fox News commentators to HBO’s improbably smug enfant terrible, Bill Maher, the directors have compiled a host of yea-sayers to defend obdurate Washington R—skins owner Daniel Snyder’s seemingly umbilical attachment to his racial slur of a franchise name.

It’s appropriate and impressive, of course, to accord the opposition such respect, even just in brief clips. It would be easy to caricature such supporters of racist mascots with the kind of broad brush that the caricatures themselves apply to the anciently-rooted but vital human cultures of Turtle Island. But More Than a Word restrains itself to drive home the fundamental ideal that we must listen to alternative perspectives, however painfully limited and finally destructive they might be.

Among the most challenging to watch in More Than a Word are the African American football fans done up in R—skins gear, tailgating before games and sharing their enthusiasm for their home team. While they do not really try to justify their claims, it is impossible not to notice and appreciate how important it is to these survivors themselves of centuries of deadly, systemic racism to insist that the team name is not disrespectful. Beneath their unconvincing protests, these fans unmistakably grasp the corrosive dangers of demeaning language and earnestly seek to convince themselves, at least, that they are not propagating prejudice.

Still more unsettling are the celebrated Navajo Code-Talkers and other Native Americans whom Snyder has successfully invited to R—skins games (especially nationally-televised ones), ostensibly to honor them for their service but clearly to use as human props for his insistent claims that the slur somehow ‘honors’ Native Americans. The film’s single greatest weakness is, arguably, its omission of their voices from the discussion; how can these decorated dignitaries allow Snyder to use them so cynically? How would they explain their willing co-optation to his brazenly immoral cause?

Ardent Advocates

Fortunately, even if More Than a Word lacks these native supporters’ first-person testimonies, it frames their and others’ opposition within such a thoughtful, varied presentation of the case against the slur that the film feels not just fair, but rich with hard-earned wisdom. Attorneys, scholars, activists, artists, and other advocates carefully and generously explain the case for conscientious name-change. Leavening patience and moral clarity with persuasive urgency, they serve the film’s cause superbly.

Although all of the advocates are well worth listening to and learning from, let me highlight two in particular. One is septuagenarian poet and policy advocate Suzan Shown Harjo, a member of the Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee nations and the original plaintiff in the case of Harjo, et al. v. Pro Football, Inc. Seated against a neutral backdrop in a jacket of muted autumn earth colors, her graying hair falling around her cheeks and down to her shoulders, her brow furrowed thoughtfully with considered purpose, Harjo rarely looks directly into the camera, but her focus and drive emerge all the more forcefully for her restraint. She is the beloved grandmother whose warm, disciplined way of speaking you never mistake for weakness and whose wisdom takes form in the explanatory shapes she is always making with her hands, affording her listeners an imaginary glimpse of the truths she has seen. As she says, “If you don’t get this one,” this movement to replace racist mascot names, “then you don’t get any of them” — the insight of a witness, survivor, and compelling leader.

Similarly impressive is Diné (Navajo) writer and social worker Amanda Blackhorse, who has followed in Harjo’s footsteps as the lead plaintiff in the follow-up case, Blackhorse v. Pro Football, Inc. The directors accord Blackhorse the honor of ending several of the film’s segments with her thoughtful questions and comments; still more tellingly, they use her explanation of the identity crisis that she and other Native Americans face to contextualize the decision of the Navajo Code Talkers (fellow members of the Diné nation) to appear at a R—skins football game. If she is young enough to be Harjo’s daughter, she is every bit as staunch and committed as her elder, and the many vulnerable moments she shares with us lend her segments still greater moral and imaginative power.

Perhaps the single most moving segment of More Than a Word records Blackhorse’s memory of Harjo’s caution: if you fight the racist mascot names through the legal system, you will ‘receive a lot of hate.’ The filmmakers insert shots of a few of the grotesquely ugly posts that social media trolls have rained down on Blackhorse, giving us just a taste of the entrenched and violent hatred she has had to endure. They cut back to her, speaking more slowly and haltingly, her voice now unmistakably colored with pain and sadness as she admits, “It has taken a lot away from me.” Beautifully underscored with slow but deeply resonating synthesizer atmospherics, this extended segment invites viewers to register the virulent hostilities that Blackhorse and other natives have faced across the generations — scorned, attacked, and killed with impunity as if they were unwelcome strangers in their own lands.

What’s in a Perspective?

Again, though, the directors know all too well that emotional appeals — no matter how authentic and profoundly moving — will never get far when self-righteous culture warriors dismiss as ‘snowflakes’ anyone who dares to question centuries of entrenched bigotry. So, More Than a Word builds thoughtfully and respectfully from Blackhorse’s most vulnerable comments toward the final affirmations.

Perhaps most delightfully, these affirmations begin with two diehard white male fans of the Washington football franchise, Ian Washburn and Josh Silver, who have been enlisting fellow fans to change the name. If More Than a Word’s omission of interviews with the Navajo Code Talkers feels like a weakness, the incorporation of these two fans constitutes one of its more improbable but striking strengths. Looking and sounding very much like many of the commentators who support the slur, Washburn and Silver don team finery (the slur pointedly absent or crossed out) to lay out a simple case for rescuing their beloved football baby while permanently throwing out the bigoted bathwater in which it’s always been immersed.

The directors accentuate Washburn’s and Silver’s comments with the same kind of subtle musical touches that accompany the native advocates’ explanations. This strategy particularly pays off with the Jewish Silver, who appropriately connects the history of anti-Semitism and the horrors of the Holocaust to the R—skin slur. Silver’s perceptive comments allow the directors briefly to show the mass grave of the Wounded Knee massacre and thus to invoke the starkest truth behind the ‘controversy’: fronting a billion-dollar sports franchise, the ‘R—skin’ slur quite literally perpetuates centuries of genocide, the U. S.’s concerted efforts to wipe all trace of indigenous peoples and their cultures from Turtle Island and replace them only with convenient caricatures for popular consumption.

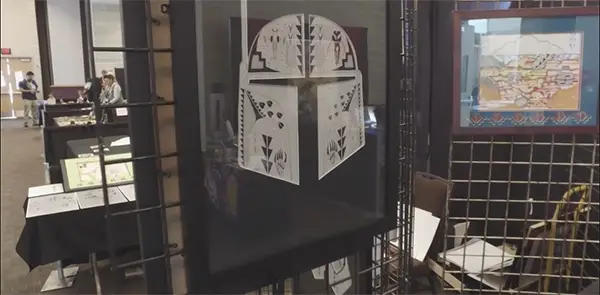

But it’s not enough to expose the lies of ‘Manifest Destiny,’ of course; the directors know they have to replace them with substantive, vital associations and new emblems. That’s what the film’s final set of advocates accomplishes, the artists and creators interviewed at the first ever indigenous Comic-Con, held in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in late 2016. In their work and the enthusiasm it is sparking among young readers, a movement is gathering to reassert native voices and traditions still more boldly into U. S. discourses, reclaiming imaginative space where so much literal territory has been wrested away.

One of my favorite shots here shows a Star Wars stormtrooper helmet reimagined with striking native traceries and motifs. If native artists can take something as whitebread as the clichéd headgear of Darth Vader’s minions and transform it into an emblem of inclusion and imaginative possibility, why can’t a professional sports franchise (with its vast economic and legal resources) give over its racist symbology and work with native artists to come up with something that really could honor deep native traditions?

Sound of a Nation

But long before we see the delightfully indigenized stormtrooper helmet, More Than a Word has served up plenty of subtle grace-notes. Notice, for example, the early montage sequence of an almost eerily calm, quiet Washington, briefly relieving the bustling capitol of the endless rush and stress of commercial hustle. The sequence lasts less than a minute, giving us a stand of Old Glories fluttering lightly in the breeze followed by shots of the National Mall as yet empty of the innumerable tourists who descend on it daily to take pictures. The subtly disquieting sequence cleverly recovers some of the ambivalence that should always attend these stone monuments named almost exclusively for white men, whose inspiring words about equality and freedom and justice have all too often rung painfully hollow for the non-white inhabitants of Turtle Island.

With touches like these, More than a Word achieves an understated eloquence that belies its modest 70-minute length. It amplifies the voice of a political movement powerfully opposed to oppression but entirely at peace with itself, working determinedly to re-bend the arc of history toward fabled (and long overdue) justice. Armed with simple but indelible truths, the film fulfills precisely the promise that its narrator, the haunting, powerful Sicangu Lakota hip-hop artist Frank Waln, delivers in “7,” one of his songs featured in the film:

This is sound of a Nation rising

A generation with a vision

We’re tired of our people dying

7th generation we have risen/ we have risen yeah

Why do we still have racist mascots?

More than a Word is an official selection of Chicago’s 2017 First Nations Film Festival. It will also be released for educational screenings and private viewings in September. Find more information on the film’s website.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Brian Walter is a college professor by day and a hopelessly sleepy college professor by night. His work has appeared in a variety of literary and film studies publications, and he appears as an 'old coot' interviewer with a magic camera in the final chapter of Donald Harington's final novel, "Enduring." He lives a short walk from the St. Louis Zoo with his remarkably patient, loving wife and a quirky assortment of canine and feline familiars.