Why I No Longer Look Forward To New Wes Anderson Films

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate,…

Something happened to Wes Anderson. Twenty years ago, he was the new auteur on the block. With indie hits like Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, and The Royal Tenenbaums, he established a distinctive style, one of charming, well-written, complex characters; whimsical and dogmatically stylized compositions; unique color palettes; and witty scripts crackling with dry humor. He has beyond a doubt the most recognizable aesthetic style in contemporary cinema.

But lately, his work has fallen off — at least for me. It’s not the overwhelming whiteness, no — that had always been there. It’s not the lack of leading roles for Owen Wilson, though that certainly doesn’t help, either. Instead, his most recent films have felt like the work of someone who’s lost touch with what made him special. It seems Wes Anderson has descended into self-parody.

His films once focused on characters who felt like real people. And though they were often isolated within meaningfully and delicately crafted frames, the characters used to be the driving force of his films. But he hasn’t made a film solely focused on characters since The Royal Tenenbaums, and ever since The Grand Budapest Hotel, his films have become increasingly more stylized. It’s more dollhouses than cinema now, each subsequent film zeroing in more and more on a particular style and craft that just leaves me cold. What happened to Wes Anderson, and how did we get here?

Art Without Heart

Wes Anderson‘s first three pictures will forever be some of his best. They show a confident yet immature artist keen to use his oddly symmetrical, folksy perspective of the world to expose fundamental truths about people. They have heart to them that is nearly impossible to find in his later works.

In Anderson’s most recent projects, you can see the technical wonder on the screen. The films are overflowing with incredible craft and design — who else would opt for a burnt orange, yellow, and teal color palette for Asteroid City besides Anderson and cinematographer Robert Yeoman? And who but Anderson could make two stop-motion pictures that feel totally and completely aesthetically united with the rest of his filmography? But after Moonrise Kingdom, the technical brilliance and craft of his films has started to overwhelmed their emotional cores. Like many great filmmakers before him — especially Stanley Kubrick — the technical excellence comes at the expense of the story and characters. Like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Anderson’s Asteroid City is a tightly wound Swiss watch in which an unwieldy cast of characters executes their lines with militaristic timing in perfectly composed frames, but there’s only rarely glimpses of soul in the picture. Asteroid City suffers from emotional deadness — as with most stories about storytelling, the film gets so caught up with its metanarrative that it forgets to be about anything else.

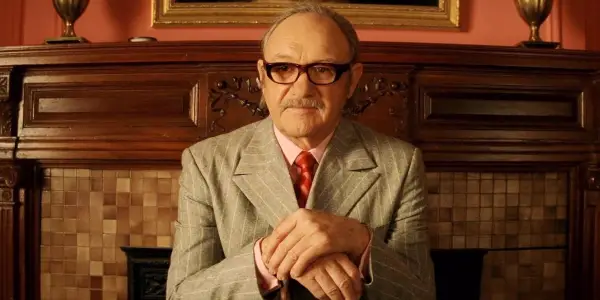

The Grand Budapest Hotel, the first of Anderson’s new mode of dollhouse filmmaking, barely manages to succeed in the story department, mostly thanks to the strength of Ralph Fiennes’ and Tony Revolori’s incredible performances. It helps that the production chugs along breathlessly at a daunting pace — it almost makes you forget that the film begins with not one but two frame narratives and three aspect ratio changes. The Grand Budapest Hotel‘s high degree of artifice hardly matters because it’s all in the service of the story.

Wes Anderson’s Casts Have Gotten Too Big

Somewhere around The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Anderson became more propelled by story rather than character — I think it’s because everybody in the industry wanted to work with him by that point. And he seems like such a nice fellow — I can’t imagine that he, in turn, didn’t want to work with everybody, too. But having a lot of friends means casting a lot of frequent collaborators, and Moonrise Kingdom was his last film with a normal-sized cast. His last six pictures, including The Phoenician Scheme and the Roald Dahl shorts he made for Netflix, have so many big-name actors in them that about half of each film poster is taken up by names.

The more actors he invites into his world, the less control each actor seems to exert over the film itself. Bottle Rocket, for example, relies every bit on the firecracker energy of Owen Wilson, Luke Wilson, and Robert Musgrave as the three principal leads. Their ’90s slacker energy nicely matched Anderson’s flair for funny, well-timed camera movements and intricately arranged mise-en-scène. But the film also has James Caan, giving one of his best late-career performances as a tough but tender Fagan figure. Caan not only helped get the film funded, but he also gave the project the legitimacy that so many 1990s indies wanted. In the final product, you get the sense that Caan’s creative vision for his character helped mold the film and, perhaps, helped Anderson to realize a more interesting version of his story.

This isn’t the only time Anderson casted big-name actors who made their careers in the 1970s and ’80s — Gene Hackman gives an unforgettable performance as the patriarch of The Royal Tenenbaums, Bill Murray brings a world-weary existential malaise to Rushmore and The Life Aquatic, and Bruce Willis shines as a small-town cop with a heart of gold in Moonrise Kingdom.

I wonder if the more established Anderson became, the less people questioned him, especially those older leading men. Hackman was especially “difficult” on set, according to Anderson. The director told The Times that Hackman didn’t want to do the film and had to be convinced by Anderson. “I talked him into it — I just didn’t go away,” he said. The director went on to sum up their relationship on-set: “He was grumpy — we had friction. He didn’t enjoy it. I was probably too young and it was annoying to him.”

For his own part, even on set, Hackman said in an interview that he was uncomfortable that Anderson wrote a part especially for him. The French Connection actor also had reservations about his performance: “The only valid way that I can act is from the moment,” he said. “I wouldn’t change my approach by the way a director chooses to shoot a film. I think you always have to be faithful or honest to your own sense of performance. You can’t cut your cloth to this year’s fashion in a way. You must always be faithful to what you know how to do. There is a certain look to the film. And I prefer not to let that affect me.” Even in the interview, conducted during the shooting of The Royal Tenenbaums, Hackman seems to feel as though his performance style was at odds with the director’s style and the overall aesthetic of the film. He implies that Anderson is merely “this year’s fashion” — a fad, a gimmick.

You can sense the conflict in the final cut. Hackman plays perhaps the biggest son of a bitch in a Wes Anderson film, capturing the ribald coarseness and the juvenile giddiness of the role with equal seriousness. He’s a live wire, and he gives the picture a soul that’s unlike any Anderson film before or since. But since Anderson prefers to treat his actors and crew like a repertory theater troupe, you can see how Hackman’s characteristic curmudgeonly attitude might’ve caused a rift between him and the director.

Not since The Royal Tenenbaums has a Wes Anderson character felt so electric and unpredictable. In contrast, in his most recent films, you can see the actors bending to the whims of the director. In The French Dispatch, for example, this sometimes works to the benefit of his actors, as Benicio del Toro, Jeffrey Wright, and Owen Wilson display a gravitas and jaded profundity that demands to be put at the center of a perfectly symmetrical shot. They’re allowed to be weird and funny and self-assured in a way they’re not in any other film. But much of the rest of the cast, unfortunately, fades into the set dressing.

Conclusion

Good as some of his recent work might be, nothing in Wes Anderson‘s recent films has touched me as deeply as Chas Tenenbaum’s heartfelt, pained admission to his father that “I’ve had a rough year, Dad.” Anderson has overdesigned every square inch of his films so that there is no life left in them. His worlds no longer resemble reality, and as such, I cannot empathize with them anymore.

I do not look forward to The Phoenician Scheme. It looks like the same overstuffed, overcasted, tightly controlled mess that he’s been making for the past 10 years. But I will watch it anyway, out of hope that it will surprise me. After all, Anderson is a rare sort of artist these days — someone who reliably produces exactly the thing you expect from them, but who, when the lights go down and the dollhouse opens, sometimes has the ability to reach out and hug your soul.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate, head of the "Paddington 2" fan club.