The Virtues of Restraint: Non-Violent War Films

Massive film lover. Whether it's classic, contemporary, foreign, domestic, art,…

If you ask somebody about the war films they’ve seen, the first titles that come to mind are usually large-scale epics that feature scenes of combat and violence. These films effectively depict the horrors of war. However, the level of action in some of these films can be distracting and compromise our emotional involvement with the characters once we see how quickly they can vanish, and the level of violence that can occur.

There’s another type of movie that exists within the war film genre. They usually revolve around the people, not the action. They take place in, or around, a war, but seldom do we see violence, or a weapon fired in anger. Movies like MASH, Biloxi Blues, Catch-22, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Streamers, and Jean Renoir’s classic The Grand Illusion show a different side of the medium that humanizes its subjects, rather than dehumanize them.

A familiar saying is “actions speak louder than words”, however, in this case the opposite is true: “words speak louder than action”.

The emotional resonance in these films is profound, not because of their depiction of war, but their depiction of life during war, which sadly is something almost everyone can relate to.

A Different Film for a New Era: MASH

Robert Altman turned movies, and the public’s depiction of the military complex, upside down in his 1970 film MASH. It’s audacious, crude, and wickedly irreverent. 20th Century Fox had three war films in production that year: Patton, Tora, Tora, Tora and MASH. It’s ironic that the low-budget comedy no one at Fox believed in persevered in the public memory.

MASH paved the way for an array of young talented actors, Tom Skerrit, Donald Sutherland, Robert Duvall, Elliot Gould, Sally Kellerman, and Bud Cort all cut their teeth in Robert Altman‘s first major success.

Modern audiences might not take to some of the sexist humor and occasional homophobia, but Altman has apologized since, reminding us that these actions come from characters in a movie, and are not a reflection of those who made it. It does take place in the fifties (not to excuse anything) and Altman described the original novel as “pretty terrible” and at times “racist” (source: 20th Century Fox Special Edition DVD Commentary by Robert Altman).

Altman took a different approach in his depiction of war. We don’t see a single explosion, and the only scene of combat is a football game between the Mash unit and the 325th Evac. That’s not to say Altman made a bloodless film. Although the movie is bloody, it’s not violent and the operating scenes serve as some of the most important in the film. Before its release, the studio demanded that the operating scenes should be edited out, but them being a crucial point of the film that Altman fought to keep them, and won.

The lengths the characters go to distract themselves from the front lines, and the graphic depiction of the soldiers coming from the front lines serves as a cautious reminder that the terror of war is never far away.

The Other Anti-War Film of 1970: Catch-22

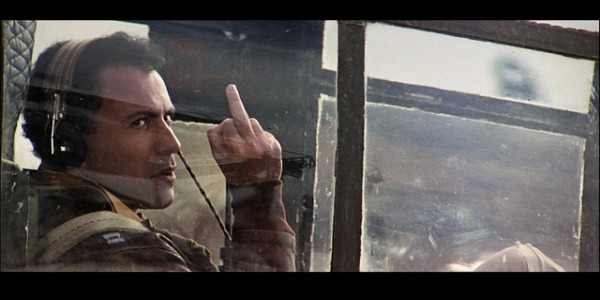

Another anti-war, black comedy came out in 1970: Joseph Heller’s immensely influential (and at the time “unfilmable”) Catch-22. Mike Nichols, whose visual sense is in full throttle for Catch-22, Heller’s novel to life, the best he can.

Catch-22 couldn’t find an audience when it came out. Since MASH came out a few months beforehand, and as the low-budget underdog, it was natural that people were rooting for Altman’s more spirited anarchistic style.* . I found that the film is genuinely funny at times, and (like MASH), boasts a large cast of young talent: Alan Arkin, Martin Sheen, Jon Voight, Art (billed as Arthur) Garfunkel, Bob Newhart, Anthony Perkins, Charles Grodin, and the great Orson Welles.

Alan Arkin was perfect in his leading role as Captain John Yossarian. Arkin commented that “it was the only part he worked on that didn’t demand a conception”, and turned out to be one of Arkin’s favorites (source: Daugherty, Tracy Just One Catch: A Biography of Joseph Heller 2011. Print). While Altman’s film succeeds in depicting the futility of war through metaphor and allegory, Catch-22 is a full-on attack on the military institution. Catch-22 takes on a surrealist quality as we witness layer over layer of full-blown absurdity.

The very phrase “Catch-22” has become a part of our language, and Yossarian’s dilemma is telling and hilarious. As an anti-war film it succeeds, but the picture hits its point too many times. And Yossarian’s character (being the only sane person in the entire air force) is a funny device, but when you see just how insane, everyone else is the jokes lose their punch, and parody gradually descends into heavy-handedness. However, some of the “jokes” don’t veer too far from some unsavory true events. Jon Voight runs a syndicate that thrives on wartime profiteering. Charles Grodin plays a young captain who murders an innocent civilian, and Art Garfunkel’s deeply devoted and patriotic, blindly going along with whatever order he’s given no matter how ludicrous. Unfortunately, wartime profiteering, and violence against civilians is a part of every war we find ourselves engaged in. Though the characterizations are humorous, the material is too somber to laugh at.

Buck Henry’s brave screenplay is commendable, and Mike Nichols captured our imaginations, but not our hearts the way Robert Altman’s MASH had earlier that year. Mike Nichols and Buck Henry succeed in satirizing the sheer madness of war. The message is delivered through the actions of the people involved, not the action that happens to the people.

Young Men in Mississippi: Biloxi Blues

Mike Nichols would hit a high note eighteen years later with his adaptation of Neil Simon’s play, Biloxi Blues. A unique coming of age tale, Biloxi Blues is an endearing and meaningful look at the juvenile men who endure a different type of war. The film is engaging as it studies two different kinds of war. One, the psychological warfare waged by their conniving first class sergeant, Merwin J. Toomey, exquisitely played to perfection by Christopher Walken. Two, the war the recruits inadvertently wage on one another as personalities and tempers clash.

Neil Simon’s autobiographical character Eugene Morris Jerome, played by Matthew Broderick, is the wise cracking, Jewish Brooklynite. He’s a naïve, young, and agreeable smart ass, stripped of any typical heroism we’re used to in war movies. Eugene is a likable, and clever protagonist whose journal serves as the film’s narration.

Although Matthew Broderick is the film’s star, Christopher Walken really steals the show as the calmly unnerving, no-nonsense sergeant. He is not the flamboyant and vulgar drill sergeant from Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, he’s a calm and self-styled sadist. He takes pleasure in torturing our protagonist and his recruits, yet, he has a strange charm that’s hard to ignore.

Biloxi Blues is a sometimes charming story that reflects on war from those who brushed against it. A coming of age tale might not be what people are looking for in a “war” film, but it’s a good story that is well made. The movie explores sexuality, camaraderie, brotherhood, religion, ethnicity, without ever leaving the barracks of Mississippi.

Another from Altman: Streamers

If you wanted to see two films that take a look at life in the barracks, Biloxi Blues and Streamers would be the best titles to choose. They both take place in the same setting, but the tone of Streamers is much darker and more troubling.

With a director like Robert Altman, who has so many films to his credit, it’s easy to overlook a few titles. Although MASH would be his paramount anti-war film, his 1983 adaptation of David Rabes’ play Streamers is another compelling look at war.

The entirety of the film takes place at the barracks where tensions grow between four young men as they await their departure to Vietnam. It’s another wonderful cast, David Allen Grier, Matthew Modine, MitchellLichtenstein, Michael Wright, and George Dzundza. To sum things up briefly, Grier and Modine strive to be gung-ho soldiers, Lichtenstein reveals that he’s gay, and Carlyle (Wright) is a black soldier who has a chip about how many African-Americans are in the military. Tensions mount as the recruits butt heads with one another. Richie (Lichtenstein) flaunts his sexuality; his fellow bunk mates make light of it (the film predates the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy) and the others don’t seem to mind Richie’s homosexuality.

However, things escalate when Carlyle raises tension between the men with his mercurial attitude and sexual proclivities regarding Richie intensify matters. The climax is explosive and disturbing, Altman’s eye for compositions, and ear for dialogue work to great effect in portraying the madness, and horrors that can happen without even going into combat.

It seems that the film is saying they’re bigger issues we need to work out among ourselves before we can justify meddling with the problems of another nation. * But Streamers is a film that about the people who go to war, not just the war itself.

Powell & Pressburger Make History Without a Drop of Blood: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

When people think of the old-fashioned English military brass, it conjures up images of an overstuffed blowhard with a white handle barred moustache. At the start of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, our leading man is just that, a portly caricature. The film opens with the good colonel fighting with a member England’s home guard who’s come to challenge Clive Candy’s old-fashioned ethics, specifically the expression “War starts at midnight.”

As our pot-bellied hero throws blows at the impatient young man he bellows out “you laugh at my big belly but do you know how I got it? You laugh at my moustache but do you know why I grew it?!”. In a few seconds, the scene transforms the caricature and introduces us to our hero. As the scene dissolves we’re introduced to a younger Clive Candy (Roger Livesey in a career-definingrole), who, like the soldier who was just quarreling, is a brash young man.

After a duel with a Prussian officer Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook), the two wounded men are sent to the same hospital to mend. As they both heal they form an unlikely, yet lifelong friendship. The representation of Candy and Schuldorff would serve as a catalyst for the rest of the films astonishing examination of war. Candy’s firm belief in ethics and honor, he trusts that high-minded fair play and British values can win a war. Schuldorff, however, is a sobering reminder of something that has no use for honesty and fair-play; nazism.

In the films most heart rendering scene, Walbrook delivers a powerful speech when he is interviewed by the UK Department of Immigration. As his monologue progresses, he elaborates “When in summer ’33, we found that we had lost both our children to the Nazi Party, and I was willing to come, she died. None of my sons came to her funeral. Heil Hitler”. The sympathy for this character is astounding, and when you consider the time the film was made this was a daring portrait for the filmmakers to draw. The emotional destruction on Walbrook’s face is jarring, and his monologue one of the most poignant parts of the film.

Roger Livesey, and Anton Walbrook were outstanding. Nevertheless, Deborah Kerr played not one, but three magnificent performances as Edith Hunter, Barbara Wynne and “Johnny” Canon. A daring and successful casting move that would be a major part for the actress throughout the rest of her career.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is probably the best depiction of nationalism by way of allegorical irony. Propaganda disguised as an anti-war parable. The main character loves his country, has a strong sense of ethics, refuses to stoop down to the level of his enemies, and knows the world only as a soldier. You don’t need explosions and flying limbs to show the horrors of war. Great acting, political relevance and good writing are more effective.

Nationalism, Ethics, and Friendship: The Grand Illusion

It’s no coincidence that I am using this film as the last in this piece: it’s because there’s connective tissue in every one of these films that either originates, or is inspired by Jean Renoir’s masterpiece. It’s a film that deals with principles of humanity, and the diversity of culture studied with an endearing eye through the confines of a German P.O.W. camp.

Like the surgeons in MASH, they used every resource at their disposal to break from the monotony of prison life. The captive prisoners devote their time to an escape tunnel dug underground whereas the confined officers pass the time in other various ways. For example, playfully annoying the German soldiers, discussing their lives before the war and putting on a show where many of the soldiers dress in drag; singing and dancing.

The Grand Illusion also coined the term “the prison escape film,” the imprisoned French soldiers take on the task of tunneling their way out of their captivity, in fact, many regard The Grand Illusion as the very first prison escape film. It’s a richly diverse film that explores humans and their relationships with one another. It maintains this lighthearted tone, captured with unimposing camera work; perfectly shot without an air of pretension.

Like Renoir’s other films, the director deftly weaves class divisions, rank, and nationalism within the microcosm of a war film. The unlikely friendship between a proletariat French soldier de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) and his captor; Erich Von Stroheim could be seen later in Powell’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Their bond is a reflection of the ageing aristocracy and its ability to persevere even in times of war.

Jean Renoir’s film summarizes everything that is relevant in this discussion: the idea of a war film that humanizes its characters and their actions. It explores morality, nationalism, social, ethical and racial standards without shedding blood or blazing combat.

With so many movies that explore the subject of war, it’s hard to pass by the titles that investigate the subject in a completely opposite way. Is the portrayal of violence on-screen a means to warn the viewer that history is savage and we ought not repeat the mistakes of the past? Or could it be that filmmakers use history to sensationalize violence to slip past scrutiny because it’s a “historical document”?

I’m not trying to cast blame, or put any other pictures down. I enjoy large scale war epics just as much as the next person. But are we watching these films for their message? Or could it be another avenue to explore violence and action?

Hopefully, these films can turn people on to a different interpretation of war, and that the subject isn’t always going to turn your stomach. At the very least, I hope those who read this will discover some new films they might not have otherwise thought to seek out.

Other films that deserve honorable mention:

- Mister Roberts– Directed by John Ford

- Stalag 17 – Directed by Billy Wilder

- Before the Rain – Directed by Milcho Machevski

- Greetings – Directed by Brian DePalma

- Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence – Directed by Nagisa Oshima

- Overlord – Directed by Stuart Cooper

(top image source: Catch-22 – Paramount Pictures)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Massive film lover. Whether it's classic, contemporary, foreign, domestic, art, or entertainment; movies of every kind have something to say. And there is something to say about every movie.