The Beginner’s Guide: John Williams, Composer

Sam is 25 years old from the West Midlands region…

In all production tools of filmmaking, using sound effects is a fundamental factor in capturing a film’s escapist experience and the audience’s reactions. Although sound is not seen on-screen, it does play a crucial role in how films work, and in how it progresses narrative, develops characters and addresses significance. John Williams is an example of a composer whose work has established the importance of music within cinema, and how they play a fundamental role in the entire experience.

Since beginning his career in the 1950s, Williams’ scores over the years have proved their value on an equal level to the screenwriting and actual production processes. This article looks at the composer’s illustrious career and how audiences do not always have to witness magic but instead listen to it.

Early Years and Breaking into Music

From a young age, the art of music began to follow John Williams from his childhood and continued throughout his professional career. His father Johnny Williams was a jazz percussionist from the 1930s through to the 1950s, after which he took piano lessons. Similar to Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) and his father Henry Jones Sr (Sean Connery) in The Last Crusade (1989), in which he composed the music for, it was inevitable that John Williams would follow in similar footsteps.

Williams was a determined student with a reputation for providing jazz and piano music among communities, one of which included the Royal Air Force. Alongside his studies, he worked as a musician in jazz clubs and became an eventual protégé of other composers, which included Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco.

Williams took inspirations from other musicians and musical style into his work, including collaborations with fellow composers Bernard Herrmann, Alfred Newman and Conrad Salinger. Williams was breaking out into the film industry through his style and acute ear for music. He continued to work as a pianist and musician throughout the 1950s and worked alongside composers to create the music of films during that period. Considering this, Williams did not reach his ultimate breakthrough in mainstream cinema until the 1970s.

Capturing Emotion: Part 1 – Suspense, Authenticity and Drama

Similar to how an actor’s duty is to perform and a director’s is taking charge of a production set, a film composer also has responsibilities. Not only do those like John Williams have to create music fitting for the finished film, but they also have to elicit a sense of emotion on part of the viewers. The music must be interpreted on a similar scale to the on-screen characters and situated scenes. Without music in cinema, the on-screen images may not be able to capture the emotional or authentic essence that some films carry at such high levels.Williams’ work is particularly significant for that, and it has been a growing talent from when he reached his first real breakthrough in cinema with Jaws (1975).

Although Williams previously worked with director Steven Spielberg on The Sugarland Express (1974), Jaws caught the attention of everyone. It became the beginning of a beautiful friendship (pun intended) between the pair. After breaking box office records, Jaws became the first real blockbuster. It also became an instant critical hit and took home four Academy Awards, one of which was for Williams’ original score.

The composer’s work on Jaws contributed to its success. Alongside the diegetic sound effects and on-screen actions, Williams’ score captured suspense, intensity and a sense of adventure. It reintroduced a new version of ‘epic’ to cinema in the sense of how music captures audience involvement and provides a whole new escapist experience. Here is an example from Jaws’ soundtrack of how the audio sounds create suspense in the absence of on-screen images:

Musicians outside of cinema like to express their emotions through music. It can be designed to capture the audience’s hearts and make them reflect on their lives. John Williams has also been known to add authenticity and, therefore, drama to his music scores. For example, Williams composed the score for Holocaust bio-pic Schindler’s List, another collaborative work with Spielberg.

Interestingly, Williams’ considered the cultural significance of Schindler’s List (1993), specifically its plot and characters, to be a challenge to score. His work was celebrated as an authentic achievement, with some critics saying that he captured the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust, but also the emotional essence of humanity in its darkest days.

Similarly, he composed the score for Saving Private Ryan (1998), a loose retelling of the Invasion of Normandy. The film was praised for its authentic representation of war, much of which was down to the on-screen technicalities and performances. On an emotional scale, though, it was Williams’ score that captured the traumatic horrors of war while simultaneously playing alongside diegetic sounds of weaponry, such as gunshots, bombs and the screams of soldiers.

Capturing Emotion: Part 2 – Adventurous & Invisible Magic

Audiences and critics worldwide may suggest that films have the power to capture dreams and magic on the screen. For the first time in the career of any composer, Williams had the capability to create this magic without even looking at it. Perhaps the first series that stood out in relation to this analogy is the original Star Wars trilogy. Particularly A New Hope (1977), its first instalment, was ground-breaking for its technology and production scale, but alongside it was Williams’ breathtaking score.

Becoming the first major steps into the adventurous scope of solar systems and space within the iconic franchise, it also became a crucial phase for film composing and creating magic with sound. Williams has since continued to compose the Star Wars franchise in The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Return Of The Jedi (1983), The Phantom Menace (1999), Attack Of The Clones (2002), Revenge Of The Sith (2005), and The Force Awakens (2015), and is scheduled to return in the yet-to-be-titled sequels Episode VIII (2017) andEpisode IX (2019). The following is a video of the artist conducting the main theme of the original 1977 film:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=285&v=4rQSJDLM8ZE

Star Wars marked the beginning of a whole new era for John Williams’ career, and he has since composed the music for other franchises. He wrote the scores for the Indiana Jones instalments – Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981), The Temple Of Doom (1984), The Last Crusade and Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull (2008). Similar to how Williams audibly captured the significant scale of space and solar systems in Star Wars, he captured adventure on our own planet and the excitement of action sequences through his music.

Even films that have no sequels, prequels or remakes, John Williams’ scores still remain timeless. In E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), for example, he interpreted the enchanting experience of witnessing a boy build a unique friendship with an alien. Listening to Williams’ score was central to that relationship, particularly in sequences like the flying bike and goodbye scene, and the drama can only make audiences cry. Watch this scene and listen to the music for an example:

John Williams continued to work successfully as the composer of other family-oriented films in the 1990s. Williams composed the score for Home Alone (1990) and its sequel Lost In New York (1992). Shortly after, he worked on Jurassic Park (1993) and The Lost World (1997). Similar to the ground-breaking extravaganza of Star Wars and Indiana Jones, both Williams achieved the innovative experience of first seeing dinosaurs (our dominant predecessors) in the magical medium of cinema. Our engagement with the music also allowed closer attachment to the films’ educational understanding of our pre-historical world.

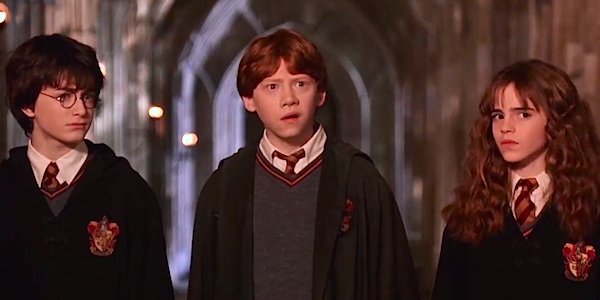

Now, as John Williams has been known to capture emotion and create magic through music, it is inevitable that he would score a franchise about magic. That’s right. He wrote and composed the scores for the Harry Potter franchise, although only the first three installments: The Philosopher’s Stone (2001), The Chamber Of Secrets (2002) and The Prisoner Of Azkaban (2004). The series became famous for presenting magic on the screen but from an audience’s perspective, the experience is also magical. This same parallel can be said for Williams’ input on the score. His themes, including Hedwig’s theme, remains as significant to the stories as the plot and characters.

Age has caught up with John Williams. Now pushing into his mid-80s, he doesn’t compose as many scores any more. However, from the few that he has worked on, including all of Spielberg’s recent films except Bridge Of Spies (2015), Williams still maintains the enchanting style of music that he has been renowned for his whole career. This summer, he is scheduled to score a live-action adaptation of Roald Dahl’s beloved novel The BFG (2016) with director Steven Spielberg. The film is a dream-like combination as all four have the power to create magic in different mediums. More importantly, though, Williams’ score will be a valuable measure to the audience’s emotional engagement and how it’ll work with the magical scale of the film. It is scheduled for release in July 2016.

Concert, Sport and TV Works Beyond Cinema

As John Williams began his career as a jazz pianist and studio magician, he simultaneously continued this work alongside his role as a film composer. If anything, his additional musical works are perhaps considered underrated. He has written other types of music including his own concerts, at the Hollywood Bowl, and themes for various Olympic Games. These included “Olympic Fanfare and Theme” in Los Angeles 1984, “The Olympic Spirit” in Seoul 1988, “Summon The Heroes” in Georgia 1996 and “Call of the Champions” in Utah’s 2002 Winter Olympics.

Williams’ greatest honour outside of cinema is perhaps his role as the conductor of Boston Pops Orchestra. He worked in this job until his 1993 retirement. Afterwards, though, he continued his music concerts regularly throughout the 1990s, including with the London Symphony Orchestra and the Cleveland Orchestra. He became the first inductee into the Hollywood Bowl Hall of Fame on 23rd June 2000.

Williams has also composed themes for television, primarily those in relation to news reports and American sports, such as the NBC Sunday Night Football. Although more renowned for film composing and his works outside of it may be underrated, he still has managed a successful career as a general musician and composer.

The most successful film composer of all time?

There is the bold yet perhaps common argument of John Williams being the most renowned film composer in history. He has certainly been the most accomplished in regards to awards, with an astounding fifty Academy Award nominations. He has won six for Original Score in Fiddler On The Roof (1971), Jaws, Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Schindler’s List. His works have also been celebrated among other organisations. For example, Jaws was ranked at number 6 and A New Hope at number 1 in the AFI Top Film Scores list.

John Williams’ work has also revolutionised the marketing of film music and soundtrack sales. Many of these have made a fortune, much as the majority of films he composed have done at the box office. Purchasing the soundtracks and listening to them at our leisure provides entertainment. More importantly, though, this success has led the audience to realise how significant music is to the entire cinema experience, especially when we don’t physically see it.

Following the success of his music upon a film’s release and the soundtracks in the aftermath, John Williams began conducting events that display his work among local arenas for the public to experience themselves. It is similar to going to a cinema, but for simply listening to music instead. Such events include when he re-crafted his Star Wars music from the original and prequel trilogies to create a show called “STAR WARS: A Musical Journey”. Therefore, even after decades he is maintaining his innovative reputation as a music composer in the film industry.

Conclusion

John Williams’ work as a film composer over many decades has simply proved the value of music on an equal level to the actual production process of filmmaking. It may not be seen on screen, but it maintains our emotional engagement with the stories and the characters. Much of Williams’ career has been carried alongside his long-time friendship with Steven Spielberg, but his long filmography list and accomplishments can only tell us that he has made a hugely successful career for himself.

Without John Williams’ breaking through into the film music industry from a jazz music background, it would have been unfortunate, because we would not have experienced the following: the enthralling excitement of Star Wars, the terrifying suspense in Jaws, the thrills of science and UFOs in Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, the sensitive relationships in E.T., the awed reaction of seeing dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, the festive delight of Christmas in Home Alone, the horrifying realities yet humble notions of World War II in Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan, our world as one whole adventure in Indiana Jones, and the magic of the first three Harry Potter films.

Do you consider John Williams to be the greatest film composer of all time? Which is your favourite Williams’ soundtrack?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Sam is 25 years old from the West Midlands region of the UK, who has a passion for the world of cinema and publishing. He is currently studying a postgraduate degree in Film & Television: Research and Production at the University of Birmingham. He is currently working in theatre and academic support.