5 Experimental Filmmakers You Need to Know About

Jax is a filmmaker and producer, and a film &…

Experimental film by its very nature often flies under the radar of the average film viewer and even most movie buffs. However, I’d like to take this opportunity to offer a sort of crash course in experimental film by highlighting five (well, sort of six) experimental filmmakers that deserve at the very least a cursory glance. These are people who changed film-making, completely threw out the rule book, and influenced cinema in very permanent and crucial ways, both with their cameras and their pens.

Stan Brakhage (1933 – 2003)

I’m starting this list with my personal favorite experimental filmmaker; so forgive any bias, but I’ll try to keep it neutral.

Stan Brakhage was one of the most prolific filmmakers ever with over 370 directing credits. Brakhage pushed the limits of possibility when it came to making films, going so far as to make a film without the use of a camera (Mothlight). He chose to remain independent which allowed him to explore controversial topics such as sex (Dog Star Man), birth (Window Water Baby Moving), and death (Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes). Brakhage often did this through the use of scratching and painting directly onto the film and superimposition with film images.

His films tend to be completely silent, unlike most other filmmakers who normally can’t resist at least some sort of sound-space. In rare instances, Brakhage would rely on images filmed in a traditional sense, but even these films break conventional conceptions of film-making. Brakhage also heavily contributed to film theory, working as a professor at the University of Colorado for many years and publishing his thoughts and theories over the time he spent there.

Len Lye (1901 – 1980)

The oldest filmmaker featured in this article, Len Lye, is also the only person on this list who primarily worked in animation. Even though he arguably influenced Brakhage and pioneered some of the techniques Brakhage experimented with in his career (painting directly onto the film strip itself), Lye was more focused on movement and color.

These interests didn’t prevent him from participating in the war effort, contributing film work to the Ministry of Information in Britain and to the “March of Time” program in the USA (source: BFI Screenonline). Also, unlike the other artists mentioned here, Lye worked in advertising for a while and had several sponsored films before finding a real distaste for it. Just speculation here, but perhaps it’s this negative relationship that steered Lye‘s protégés away from the mainstream.

Kenneth Anger (1927)

Kenneth Anger has become sort of a Hollywood mythical figure. Growing up in Los Angeles, he’s one of the earliest experimental filmmakers and one of the first filmmakers to openly deal with homosexuality in his films. His film Fireworks (1947) vividly depicts anti-gay hate crime and is clearly very personal to the filmmaker.

The occult, violence, and homosexuality are common themes throughout Anger‘s work and his in-your-face style attracted the collaborative efforts of artists like Mick Jagger. Jagger composed the soundtrack for Invocation of My Demon Brother, and both the film and soundtrack were experimental and groundbreaking. Now, at the age of 87, Anger remains a somewhat active filmmaker and social commentator (he’s published two volumes on Los Angeles life titled “Hollywood Babylon”).

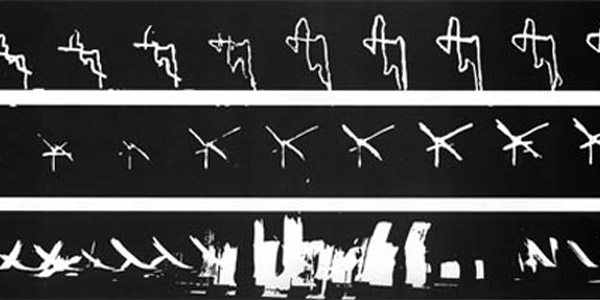

Luis Buñuel (1900 – 1983) and Salvador Dalí (1904 – 1989)

Surrealist cinema isn’t as common as it once was but you can’t deny its presence and you can definitely argue its influence on filmmakers like David Lynch and Terry Gilliam. Most people think of Dalí only in terms of his painting, but his work with Buñuel in cinema, particularly Un Chien Andalou, was revolutionary.

The film purposefully makes very little sense and is designed to confuse the viewer. This signaled the beginning of independent and experimental cinema and opened the door to shock cinema, as well. Buñuel would carry on making surrealistic cinema well into seniority, using surrealism to critique society and especially the upper classes, notably in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Phantom of Liberty.

Maya Deren (1917 – 1961)

Female filmmakers tend to get pigeonholed into specific stereotypes. Maya Deren was one of the first woman filmmakers and still one of only a handful of female experimental filmmakers. She managed to avoid many of the clichés we associate with female directors, experimenting with editing, repetition, and sound; this is highly evident in her film Meshes of the Afternoon, which she co-directed with Alexander Hammid.

Not only did Deren pioneer in film-making, but she lent herself to pushing film theory, publishing several papers and articles on the subject, and rising as one of the most respected experimental filmmakers and theorists to this day. Deren also supported the idea of completely independent cinema, holding living room screenings and avoiding the idea of Hollywood distribution – a trait of experimental cinema that, either to its benefit or cost, remains today.

This is by no means a fully comprehensive list, but is meant instead to provide a jumping ground and hopefully foster some interest in a lesser known area of cinema. The filmmakers discussed here are hugely influential figures but by no means is this the limit of experimentation and that’s the the point! The strides these filmmakers made continue to inspire filmmakers from all ends of the spectrum – if you look for it you can find techniques that began in experimental cinema in even some of the most mainstream Hollywood films.

What are your thoughts on experimental film? Too weird for you or is it mind expanding? Tell me in the comments section!

(top image source: Un Chien Andalou – source: Les Grands Films Classiques)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Jax is a filmmaker and producer, and a film & tv production lecturer at the University of Bradford and is also completing a PhD about Stan Brakhage at the University of East Anglia. In the remaining "spare time", Jax organises the Drunken Film Fest, binges bad TV, and dreams of getting “Bake Off good” with their baking.