The Beginner’s Guide: Coen Brothers, Directors

PhD Student in Culture, Film and Media at the University…

Since they first hit cinema screens in 1984, the Coen Brothers have had a firm grip on audiences and critics alike. Renowned for their idiosyncratic, high quality work, they have found themselves increasingly in demand with studios and actors, many of whom aim to make their next project a Coen Brothers film. They have written, directed and produced all of their own pictures, edited most of them, and have recently ventured into the ‘gun for hire’ realm of screenwriting, contributing to Steven Spielberg‘s Bridge of Spies, Angelina Jolie‘s Unbroken, Michael Hoffman‘s Gambit, and George Clooney‘s upcoming Suburbicon.

Remaining somewhere between the kooky cousin and the affectionate but cynical uncle of Hollywood, the Coens have successfully managed to straddle the independent and the mainstream throughout their career. They have also managed to defy genre classifications, with the most suitable epithet for most of their work being that of the ‘black comedy’, though this is still insufficient to appropriately convey the scope and content of their films. Their most significant trademarks have been their rhythmic dialogue, a propensity for surreal plot twists, and a veritable retinue of reliable cast and crew members, including John Goodman, Frances McDormand, George Clooney, Tricia Cooke, Skip Lievsay, and Roger Deakins.

The Early Beginning

The Coens are notoriously enigmatic and/or evasive in interviews and have admirably managed to keep much information about their private lives and their childhoods secret from the public. What is known is that they were born in the mid and late 1950s in Midwestern America to Jewish intellectual parents, their father a lecturer in Economics, with their mother an art historian. After making a series of films on Super 8 cameras as kids (such as Henry Kissinger: Man on the Go) and reading lots of pulp fiction (especially Dashiell Hammett), Joel Coen went on to study film at New York University, while younger brother Ethan studied philosophy at Princeton.

Having worked as an assistant editor on The Evil Dead, Joel started a friendship with new independent filmmaker Sam Raimi. The brothers also befriended cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld and set to work on producing their own first picture Blood Simple. It was also on this film that Joel met his second wife Frances McDormand, with whom he remains happily married to this day. Ethan would go on to marry editor Tricia Cooke, who had worked with the brothers from Miller’s Crossing onward.

In terms of their influences, the Coens have stated their admiration for Sam Raimi, Stanley Kubrick, Alfred Hitchc*ck, and David Lynch, with the latter sharing the Best Director award at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival with the Coens for his film Mulholland Drive, much to their excitement. They had won for The Man Who Wasn’t There – fitting, given that this was the most Lynchian of their films, featuring a bizarre subplot about alien abduction theories and a bleak, unsettling tone throughout.

The brothers also have a number of key literary influences, including authors Dashiell Hammett and James M. Cain, with much of the plot of Miller’s Crossing based on the narrative of Hammett‘s novel Red Harvest, a book that also provided the title for the Coens‘ first feature. Their own work has been further enhanced by the fictional editor Roderick Jaynes – a pseudonym employed by the brothers themselves. As well as editing their films, Jaynes has provided a number of humorous cover letters to their scripts and has even been nominated for Academy Awards.

Until The Ladykillers, the Coens were – despite their public persona and their obvious directorial collaboration on set – individually credited on their films, only sharing joint credit for their screenplays. Joel was credited as director, while Ethan was credited as producer until 2004, when the Coens received joint credit for writing, directing and producing their films for the first time (and have done so ever since). The reason for this has never been entirely clear, as the brothers have always worked together on every aspect of their productions, and actors have found themselves receiving corresponding notes from each of them individually. It has been suggested that one of the reasons for this could have been bizarre union rules that prohibited joint directing credits until a suitable number of films had been made between the duo, but this has never been confirmed.

What is clear, however, is that the brothers have an excellent working relationship and continue to go from strength to strength as filmmakers, with some of their finest and most refined work coming in recent years. Not every film they have made has been a hit, though. Like most directors, they have created some great and some not-so-great pictures. Having learnt a little more about the Coens as people and as filmmakers, it is probably best now to discuss their films.

It is hard to know which of the Coens’ films to suggest first to the unfamiliar or newly-initiated viewer. A more accessible genre movie like True Grit or a lighthearted comedy like O Brother, Where Art Thou? might seem the obvious choice, but then Fargo has been called the best and most quintessentially Coenesque film in their repertoire, while some others might favour the linear approach and choose their debut Blood Simple as the best introduction to their work. In order to continue to learn more about the Coens themselves, and see how their career has developed, the latter approach will be taken. Beginning with Blood Simple and ending with Hail, Caesar! (before a brief look at the potential future), the following article will examine each of the Coens‘ films – as well as their production and reception – in chronological order.

So, without further ado, let’s get started!

Getting Some Attention

The making of the Coens‘ first feature was a learning curve for the young and ambitious filmmakers. In order to raise money, they shot a trailer for their non-existent picture, featuring a couple of rough versions of scenes from their script filmed by Barry Sonnenfeld, while they filled in for actors. Eventually, after a year of fundraising, rejections and accidentally bumping a potential investor’s car in their driveway, the Coens managed to scrape together the necessary $1.5 million to make their movie.

The script itself for Blood Simple had already been written. The story concerned a woman who has an affair with one of her controlling husband’s employees, prompting her husband to hire a private detective to follow her for proof before eventually commissioning the sleuth to kill her and her lover. This does not go smoothly, however, and a series of complicated events sparked a chain of murder, deceit and confusion.

Having secured the funding and the script, the Coens now needed locations and a cast. Their screenplay had called for a Texas setting, and they had managed to secure appropriate sets and sites with little difficulty. Their crew mainly consisted of non-union film workers to keep down costs, a number of whom became long-term friends and collaborators, including Sonnenfeld, composer Carter Burwell, and sound editor Skip Lievsay.

When casting the film, the Coens had initially offered the lead role of Abby to Holly Hunter after seeing her onstage in Crimes of the Heart. However, Hunter was unavailable for the 48-day shoot and so suggested her friend and roommate Frances McDormand, who auditioned successfully for the part. Hunter did receive an uncredited voice-over role, though, and was the lead in the Coens‘ next picture Raising Arizona. The rest of the principal cast featured more experienced actors John Getz, Dan Hedaya, M. Emmett Walsh, and Samm-Art Williams. The Coens had auditioned each of these actors, with the exception of Walsh, whom they had approached directly.

Walsh was certain that the film would be a fun experience and a good chance to earn a bit of money, but had no high hopes for the success of the picture itself. As it turned out, he was wrong. Blood Simple went on to attract intrigue from critics and audiences alike, with Circle Films distributing it and securing the rights for three more of the Coens‘ projects, while its cinematic release doubled its budget, giving the film a $1.5 million profit. Moreover, critics praised the Coens‘ sense of humour, ambitious and well-executed framing, and Walsh‘s performance as the highlights of the picture, while the film went on to receive a number of accolades at various independent film award ceremonies.

The film was not without criticism, however, which was somewhat warranted. It is an excellent first picture with strong performances, striking imagery, a mordant sense of humour, and a clear understanding of the medium of film, but there are some performances that are weaker than others and there is much more style in the film than substance. This latter critique is one that would go on to be a constant bug-bear for less enthusiastic viewers of the Coens‘ work, but it is generally not a sufficiently strong argument to carry weight. In Blood Simple, though, there is much more of an emphasis on pastiche and atmosphere than there is on character and story, and it is clear that the Coens were experimenting and trying to make themselves stand out with their debut feature. This is as much a strength of the film as it is a weakness, but it does allow for detractors.

The Coens have always been candid and self-conscious in their work, refusing to discuss it thematically or analytically in any serious manner, claiming that their sole intention is to entertain and let audiences take from their films what they will (since they will do this anyway). This has brought them as many fans as it has critics, with a number of their films being accused of shallowness at best and offensiveness at worst. The most shocking example of the latter came with Miller’s Crossing, when the Coens were accused of homophobia and anti-Semitism because of the inclusion of a greedy Jewish homosexual antagonist. The film is, of course, not remotely homophobic or anti-Semitic, but it certainly caused some friction and brought the Coens under unnecessary scrutiny.

Despite such blips and grievances, however, the Coens have been able to craft a consistently successful career and have been intriguing audiences, filmmakers and reviewers alike with their work ever since. All of this started with Blood Simple and, since stepping into the spotlight with their debut, they have never left it. Indeed, off the basis of Blood Simple, up-and-coming actor (and nephew of Francis Ford Coppola) Nicolas Cage expressed his desire to work with them, which they were all too happy to oblige. What is more, following their first two features, the Coens had clearly shown that they had enough talent and commercial pull to be offered the directing chair on the new Batman film, which eventually went to fellow newcomer Tim Burton after they had turned it down.

In short, the Coens had grabbed some attention and they weren’t going to let it go.

The Circle Films Years

After the success of Blood Simple, the Coens wrote a new script designed as a human cartoon about reformed convict H. I. McDunnough, who marries police officer Edwina and looks to start a family. When it turns out that ‘Ed’ is unable to conceive, all seems lost until the couple spot a news report detailing that wealthy businessman Nathan Arizona and his wife have just had quintuplets, which they deem to be too much to handle. In their own words, the childless protagonists think it unfair that some should have so many while others should have so few, and so they conspire to steal one of the infants and raise it as their own, which of course doesn’t quite go to plan.

There are some hilarious and touching performances in Raising Arizona – particularly from Nicolas Cage, Holly Hunter, John Goodman, and Frances McDormand – and Sonnenfeld‘s bouncy and colourful cinematography is very impressive, adding a tangible sense of caricature to the film and giving the feel of cartoon-meets-storybook – a technique later employed on O Brother, Where Art Thou? The film has been received as a parody of the Reagan presidency and the effect this had on people’s attitudes and values, with some becoming selfish and others desperate, though what with the Coens‘ refusal to talk politics this could all be hot air. Even with mixed reviews, the film was very successful at the box office, earning $22,847,000 against a $6 million budget despite being released in the same week as blockbuster action comedy Lethal Weapon.

Some critics hated the film, with Roger Ebert criticising its archness and artificiality as its downfall, while Sheila Benson found it boring and disliked what she perceived to be a tone of superiority towards its characters. Many continued to see potential in the Coens, and others like Pauline Kael even praised the film for its charm and efficient handling of surrealist comedy. Benson‘s critique, however, touched on another consistent cause for backlash against the Coens, in that their constant use of ineffective and foolish central characters has seen them come up against accusations of snobbery and elitism. They have constantly denied this, claiming that they do have a sympathy for their characters and that they simply like using more identifiable, bumbling characters in their narratives for comedic and dramatic purposes.

This is certainly true in Raising Arizona, where no one would bat an eyelid if the same characters had been depicted in the same manner in an animated feature, but because it is real people it creates an aesthetic and artistic block for some viewers, which would later become a problem for The Hudsucker Proxy (see below). Furthermore, beyond the stylistics, the film has a clear moral centre in the shape of the sympathetic and tragic character of ‘Ed’, who reforms both herself and her husband and restores harmony to the natural order by the end of the film. She is also helped by the paternal Nathan Arizona, who encourages her to stay with her husband and not to lose hope for a family some day.

Despite a subsequent appreciation, the Coens‘ next film for Circle was lukewarm with critics and lost out at the box office. Miller’s Crossing is a convoluted gangster flick about an advisor to a crime boss in 1930s America, who must deal with a double-crossing smalltime hustler and an impending mob war between the city’s rival Irish and Italian crime syndicates. It had a warm reception from Variety, which predicted greater success for the film than Dick Tracy, a film deemed equally stylish, more high-profile and released at a similar time, but was apparently lacking in substance. This, however, proved inaccurate, as the Coens failed to compete with Warren Beatty‘s film, having also been hampered by a shared release week with Martin Scorsese‘s Goodfellas, which earned big money, critical plaudits and awards considerations.

While Goodfellas is a better film, this is somewhat of a shame, as the Coens‘ picture was witty, tense and extremely well-plotted, with a nice balance between its influences and its own originality that allowed it to be more than a standard genre piece. It also sported some excellent performances from Gabriel Byrne, Marcia Gay Harden, John Turturro, and Albert Finney, while Steve Buscemi had a delightful cameo. The surreal violence of Sam Raimi was celebrated first by an extraordinary ‘Tommy Gun’ sequence, before a brief cameo from the director himself as an arrogant and unfortunate gunman. It is one of the Coens‘ finest films to date and was certainly the best of their works for Circle Films, so it is unfortunate that it received such a limp reception upon its initial release.

Their final feature with Circle, however, was their first major success. Barton Fink was nominated for three Academy Awards, won an unprecedented triple award at Cannes (Best Director, Best Actor and the Palme d’Or), broke even at the box office despite being a self-conscious, surreal arthouse picture, and, perhaps most importantly, was referenced in an episode of The Simpsons (which is how you knew you had made it big in 1991). It also won over some of the Coens‘ biggest skeptics, including Vincent Canby, Roger Ebert and Christopher Tookey, while Empire, Variety and Time Out published glowing reviews. In particular, Roger Deakins‘ cinematography, the Coens‘ direction and the central performances by John Turturro and John Goodman were heavily praised (and rightly so). There was still concern that general audiences would not be able to access the joy of the Coens‘ work, which was deemed yet another example of elitist, postmodern, overly-referential filmmaking, which allowed the creators and the fans the chance to reward themselves for being in on the joke at the expense of other viewers.

This argument, however, neglects the Coens‘ talent, diminishes the emotional and comedic impact of the film, and patronises the audience it claims to support. While it is true that audiences feel alienated by indulgent material, it is possible to enjoy Barton Fink regardless of your knowledge of Old Hollywood. Also, as much as the Coens are film buffs, their work is inspired as much by popular culture and genres as anything else, mixing moments of broad comedy, horror, and thrillers with their satirical take on 1940s Tinsel Town.

Barton Fink is a funny, scary, genre-hopping picture that gleefully flits between surreal black comedy, caricature and Gothic horror. Its tale of a New York playwright-turned-Hollywood screenwriter staying in a creepy hotel, finding himself increasingly alienated by the weird and insincere home of the movies, is oddly powerful and utterly gripping, thanks largely to an outstanding supporting turn from John Goodman as the non-intellectual everyman Barton befriends.

The Circle Films pictures brought the Coens much critical success, and confirmed their place amongst the best independent filmmakers on the rise in the early 1990s. They also brought a number of long-lasting collaborations and friendships, including cinematographer Roger Deakins, the late costume designer Richard Hornung, production designer Dennis Gassner, and actors John Goodman, John Turturro, Steve Buscemi, Jon Polito, Michael Badalucco, Harry Bugin, John Mahoney, Tony Shalhoub, Michael Lerner, Bill Cobbs, Marcia Gay Harden, Holly Hunter, and Frances McDormand.

Having stuck their flag in the ground, the Coens were offered a chance to make a big-budget film and cross over into the mainstream. Unfortunately, it would take a little longer than expected.

Silver Isn’t Gold

Producer Joel Silver – whose credits include The Matrix and the Guy Ritchie-helmed Sherlock Holmes franchise – had been behind the successful Die Hard and Lethal Weapon series, and was looking for a project to work on with the Coen brothers. They came to him with a script they had written in the mid-1980s with Sam Raimi, who also acted as Second Unit Director on the final film.

The screenplay was a surreal comedy about a hapless businessman who moves to New York and struggles to get up on the entrepreneurial ladder. As luck would have it, he is headhunted to become the new president of Hudsucker Industries, following the sudden suicide of its owner and chair Waring Hudsucker. Unbeknownst to him, he is given this position to act as a stooge for the greedy board members, who hope to take control of the company by buying it cheap when investors have become sufficiently antsy at his arrival, allowing the stock to plummet. An intrepid reporter smells something fishy, so she disguises herself as a secretary in the hope of exposing the fraud.

The Hudsucker Proxy remains the Coens‘ biggest commercial and critical flop to date. Despite retroactive and enthusiastic support from the likes of Mark Kermode, it was universally panned for its cartoonish nature and lack of substance. To make matters worse, this beguiling comedy took a mere $2,816,518 against an estimated $25-28 million budget, depending on the source. Again this was partly due to bad luck, with the film released in the same week as surprise smash hit Four Weddings and a Funeral, but its silly, frantic story and poor notices couldn’t have helped its chances. The film’s failure is a particular shame given the good working and personal relationship that existed between the Coens and Silver, as well as the faith and passion he put into promoting and funding the picture in the first place. Indeed, their working relationship ended abruptly, and the Coens‘ were left with few options for funding their next film.

It seemed that the innocent charm and energetic fun of The Hudsucker Proxy had failed to find an audience and that the Coens had blown their chance at mainstream success. That was, at least, until their next film…

This is a True Story

Despite the commercial disaster that was The Hudsucker Proxy, British productions company Working Title (and distributor Polygram) were keen to work with the Coens again, and put forward all of the $7 million budget they needed for Fargo. In contrast with Hudsucker, Fargo grossed nearly $51 million worldwide. It also did better with critics and awards, with sweeping positive reviews and seven Oscar nominations, of which it won two – Best Actress for Frances McDormand and Best Original Screenplay for the Coens. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert put it in each of their top ten films of the year and it remains one of the most revered and referenced of the Coens‘ films in popular culture to this day, even spawning the inspiration for a so-so TV series.

But what was so great about Fargo? Was it because the plot concerning a struggling businessman who pays an incompetent and a psychopath to kidnap his wife to extort his wealthy father-in-law was based on a true story? Or was it that it wasn’t based on a true story at all, but was in fact an entire fabrication inspired by a fleeting resemblance to a news story the Coens had once heard about? Either way, its quality cannot be denied, and the risky move to put a disclaimer at the beginning of the film stating its authenticity was a sublime joke to play on the audience.

The film ran into greater controversy, however, when a Japanese woman was found dead in the wintery landscapes of Minnesota, having reportedly become obsessed with the film and traveled to America in search of the $1 million buried in the snow by Steve Buscemi‘s character. Nevertheless, the case was proved to be an urban legend, with later evidence suggesting that Takako Konishi was suffering a major bout of depression, and so had sold off her possessions in Japan and traveled to America to commit suicide in a location she had previously visited with her former boyfriend. Both the urban legend and the more tragic real story behind it have been subjects of films themselves – the fictional Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter and the documentary This Is a True Story respectively.

The Coens‘ reasoning behind the fabrication may have been as a reaction to the criticisms they faced for making artificial, unrealistic movies. They have argued in the past that realism is as much an artistic aesthetic as other, non-naturalistic styles, and that the audience’s expectations and attitudes change when they are presented with a film that is based on real events – or at least one that tells them it is. More than a challenge to audiences, however, the uncharacteristically realistic palette and tone of Fargo was a challenge to the Coens themselves, and they passed with flying colours.

Working Title: Cult Hit, Hayseed and Cannes

Much more characteristic was the Coens‘ decision to follow up their biggest, most accessible critical and commercial hit with an oddball film about a lazy stoner investigating the kidnapping of a wealthy businessman’s young bride. Across the course of the picture, ‘the Dude’ comes into contact with German nihilists, bumbling private detectives, amateur bowling champions, a juvenile car thief, and the LA porn industry. Though nominally based on Raymond Chandler‘s novel The Big Sleep, The Big Lebowski is a chaotic cacophony of tone and style with a series of bizarre events, culminating in an episodic stoner movie/black comedy thriller, referencing everything from Busby Berkeley dance routines to the music of Kraftwerk.

At the centre of the mayhem are two fantastic comedic performances from Jeff Bridges and John Goodman, with delightful cameos and supporting turns from Julianne Moore, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Steve Buscemi, John Turturro, Sam Elliott, David Thewlis, Peter Stormare, Ben Gazzara, and Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Though many critics didn’t know what to make of the film upon its initial release, it made a decent profit and has become one of the most popular cult movies of all time. It has also inspired its own religion (Dudeism), an annual convention (Lebowski Fest), and a book focusing on the influence of the film on fans, cast, crew and extras. The book is called I’m a Lebowski, You’re a Lebowski: Life, The Big Lebowski, and What Have You and features a quote from the Coens by way of a prologue that simply says “They [the authors] have neither our blessing nor our curse.”

Following from this, the Coens made another silly film, but this time to much greater acclaim and box office success. O Brother, Where Art Thou? was a Three Stooges-type musical comedy about three convicts who escape from a chain gang and try to make it to a plot where one has claimed to have buried treasure. Throughout their journey across the Depression-Era South, the heroes encounter a wickedly talented guitarist, a crooked Bible salesman, the Ku Klux Klan, warring politicians, gangster George ‘Baby Face’ Nelson, and a sheriff who may well be the Devil himself. During their travails, they attempt to patch up a marriage and accidentally become a musical sensation to all the weary folk looking for some light relief in hard times.

The film is very, very loosely based on Homer‘s The Odyssey, to the extent that the Coens claim never to have actually read the full original text, using only the basic outline of the story for the structure of their film. More important is its use of period folk music, rerecorded by contemporary folk musicians, and arranged and produced by music producing legend and folk boffin T Bone Burnett, who had worked as a music supervisor on Lebowski. The film’s soundtrack won a Grammy award for Album of the Year, going platinum eight times and selling 7.9 million copies to date.

The film itself was nominated for two Academy Awards – Best Cinematography and Best Adapted Screenplay – though it was successful in neither category. O Brother is probably the Coens most accessible film and certainly a good introduction to their work – fun, stylish and expertly-crafted, with an episodic narrative and a love of music and capering. It also marked the first feature from their film company Mike Zoss Productions, which has since produced all of their films as well as Down from the Mountain and Bad Santa.

Amongst O Brother‘s finest achievements was its use of pioneering digital rendering and colour editing in its cinematography. This had to be attempted because the Coens wanted a sepia-toned, storybook aesthetic that was impossible in the lush, green surroundings of Mississippi at the time of filming. Roger Deakins and his team spent months in their labs working with the 35mm negative to get it up to standard, and the result is utterly wonderful.

The Coens‘ next picture brought them back to both their neo-noir roots and the Cannes Film Festival. The Man Who Wasn’t There follows a barber named Ed Crane, whose wife is having an affair with her boss at the department store she works in. Ed does not much mind her infidelity, but needs money to invest in a dry-cleaning business and so decides to anonymously blackmail her lover for the $10,000 he requires. However, things take a dark and unexpected turn when his extortion is discovered.

Billy Bob Thornton‘s excellent central performance was criminally overlooked in what is one of the Coens‘ least appreciated films. Despite good reviews, a little profit at the box office, a directing award at Cannes, and an Oscar nomination for Best Cinematography, the film seems to have drifted into the background. This is especially frustrating given the lengths to which Roger Deakins had to go (yet again) to achieve the right look for the picture. The Coens wanted the film to be shot in monochrome but were bound by a distribution contract to prepare a colour print, which meant it had to be shot in colour and printed on black and white stock in post-production. This would have been fine, except that it meant Deakins had to work with the costume and set departments to ensure that their colour palette would work on both colour and monochrome film stock, while he also had to carry round a black and white photo camera on set at all times to correct lighting and filtering so that both stocks would be of an equal quality – which they were, especially the monochrome print.

We All Have Bad Days

The next two films on the Coens‘ CV represent a bit of a low point in their career. Intolerable Cruelty was a romantic comedy trapped in development hell for ten years at Universal Studios when it came to their attention. Redrafting the original script by John Romano, Matthew Stone and Robert Ramsey, the duo attempted a more formulaic, mainstream, lighthearted project, reminiscent of 1940s screwball comedies. The film paired George Clooney with Catherine Zeta-Jones, and followed the unlikely romance between a greedy, womanising divorce lawyer and a revenge-driven socialite keen on taking her husband for all he’s worth.

Unfortunately, the film falls flat due to a limp chemistry between its leads and a stiff and unsympathetic central performance from Zeta-Jones. There are some amusing moments – including a terrific opening sequence starring Geoffrey Rush – but for the most part Intolerable Cruelty is somewhat mediocre and a little disappointing, lacking the Coens‘ usual flare, energy and eccentricities.

Much more of a disappointment, however, is their remake of Alexander MacKendrick‘s The Ladykillers, which is perhaps the worst film they have made to date. It isn’t completely without merit – Tom Hanks is rather funny as the mannered and slimy Professor G. H. Dorr, and the film is at least entertaining – but given the quality of its source material and everyone involved, it is hard not to view it as a waste. What is more, the updated setting and adoption of the ‘ironic’, racially-charged and boundary-pushing humour of Marlon Wayans is ill-advised and uncomfortably executed. It may not be a terrible film, but it is poor by the Coens‘ standards and somewhat underwhelming, having been received poorly by critics and audiences alike.

Paris, Texas

After The Ladykillers, the Coens fell silent for a few years, only emerging for a short film starring Steve Buscemi that served as part of the collaborative anthology film Paris, je t’aime. An explicitly romantic film that served as an efficient love letter to and tourist promotional tool for the French capital, the Coens‘ contribution was the most irreverent – an amusing vignette in which a silent American tourist waits on the Tuileries Metro platform, before accidentally flirting with a young woman and receiving a beating from her lover for his pains.

It was not until 2007, however, that the Coens would return with their next full-length picture. The result was one of their most iconic and successful films to date, earning them popular and critical recognition, and four Academy Awards (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actor for Javier Bardem). No Country for Old Men is a bleak, violent and powerful adaptation of Cormac McCarthy‘s gritty novel set in 1970s Texas. It follows the misfortunes of a man who finds a case full of money and unwisely takes it, unaware that he is being tracked by a crazed serial killer who works for the drug cartel that owns the loot.

It is an incredibly well-made film, with a sinister tone, strong performances, striking visuals, an unsettling sound design, and no score until the end credits, adding an extra layer of tension as the audience waits for the relief of incidental music that never arrives. After Fargo, No Country for Old Men probably marks the biggest turning point in the Coens‘ career, and harks back to the tone and themes of Blood Simple, Fargo and The Man Who Wasn’t There. It proved that the brothers were as good as they ever were after a double bill of disappointing features, and finally brought them fully into the realm of the mainstream, albeit on the outskirts.

On a Roll

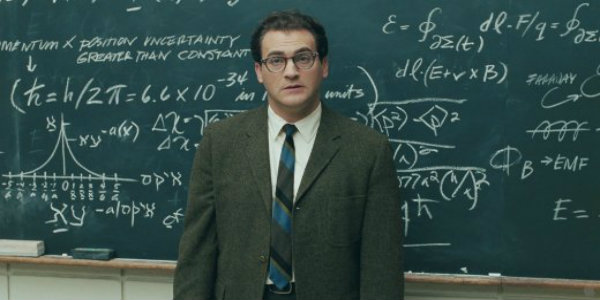

Starting with No Country for Old Men, the Coens have been on somewhat of a roll. Burn After Reading marked a return to the frivolous and quirky with a black comedy centered on a group of wealthy Washington socialites, who create a lot of noise over nothing and eventually become embroiled in murderous mayhem concerning a perceived threat to national security. A Serious Man was a more refined tale about a Midwestern Jewish Physics lecturer who finds his family life suddenly falling apart.

True Grit was more a new adaptation of Charles Portis‘s original novel than it was a remake of the 1969 film starring John Wayne, and followed the efforts of a young woman seeking justice after the murder of her father. Inside Llewyn Davis concerned a down-on-his-luck folk singer in early 1960s New York, with a character and plot loosely based on the experiences of Dave Van Ronk. Finally, Hail, Caesar! acted as the lighter B-side to Barton Fink, centering on a day in the life of a fictionalised version of real-life Hollywood fixer Eddie Mannix, who must deal with a kidnapping, a pregnancy scandal, an unhappy director, and a pair of gossip columnists.

Each of these films have shown the Coens‘ ability to reign in some of the mayhem of their earlier works, leaving more room for the development of ideas and character, with some of their finest films to date. A Serious Man is an overlooked gem featuring excellent performances from Michael Stuhlbarg and Richard Kind, and a surprisingly poignant and moving tone for a Coen brothers film. Inspired by the Book of Job, it manages to be both broad and artsy, with existentialist undertones that avoid pretentiousness and offer a simple but meaningful reflection on life and the challenges it presents.

True Grit is a mature and powerful film, beautifully shot by Roger Deakins, and centered round a fantastic performance from Hailee Steinfeld. More than a simple revenge flick, it adds a layer of spirituality and emotional depth to a coming-of-age story set firmly within the western genre. It is far better than the original film adaptation, which gives greater attention to the Rooster Cogburn character and weakens its protagonist Mattie Ross (who is actually the one with true grit all along). Indeed, The Revenant could have learned a lot from the Coens‘ more subtle and unashamedly romantic tone.

Moreover, Inside Llewyn Davis is arguably one of the Coens‘ best films. A frank, affectionate, personal, and moving portrait of the Folk Revival of the early 1960s, with a subdued and sombre tone and an outstanding lead performance by Oscar Isaac, it is a grossly underappreciated film that will hopefully receive greater recognition in time. Its use of on-set recordings and contemporary folk musicians doubling up as underground performers of the early 1960s adds a sense of nostalgia and verisimilitude that raises the quality of the entire picture, and provides a Coens‘ film with yet another fantastic soundtrack. It is the third and finest instalment in what I would like to call the ‘Serious Coens Trilogy’, and it is well worth a watch.

But after the delightfully silly romp that was Hail, Caesar!, what will come next?

Future Projects

In the immediate future, it has been confirmed that the Coens‘ are working on a TV detective movie called Harve Karbo, that will likely star Billy Bob Thornton in the titular role. Currently moving into production, however, is a screenplay they have written for George Clooney to direct, with a cast so far including Matt Damon, Julianne Moore and Josh Brolin. The film is slated for release in 2017, is called Suburbicon, and is said to be a crime drama reminiscent of Twin Peaks about a seemingly perfect family who turn to blackmail and betrayal after preventing a break-in to their home. Also on the cards is a commission from none other than Joel Silver to write (and potentially direct) an adaptation of Ross MacDonald‘s novel Black Money for Warner Bros.

Furthermore, the Coens have repeatedly spoken about making a sequel to Barton Fink, appropriately called Old Fink. The film would rendezvous with Barton in the 1960s, where we find the writer teaching at Berkeley College, having named names of his Communist friends to the House of Un-American Activities Committee. The Coens have said that they are waiting until John Turturro is sufficiently old enough to play the part to make the film. It is, however, hard to tell whether they are joking or not.

Conclusion: We All Have That Coen Feeling

Over the course of the last 32 years, the Coens have proven themselves to be master filmmakers who only get better with time. Their mordant sense of humour, irreverent mix of standard and unconventional styles, and their repeated conformity to and subversion of genres and tropes has remained a popular and intriguing method, with new fans emerging with every new release and the (re)discovery of their back catalogue. For the uninitiated and dedicated viewer alike, there is much delight to be had in their work, and the matter of where best to start is, in the end, irrelevant.

Ultimately, what gives the Coen Brothers their power is that they know how to make films for audiences as much as for themselves, and they have learned to temper their temptation to do the latter. They have a bizarre ability to wryly tap into what turns us on about cinema, and are perhaps the most effective comedic writers in Hollywood working today. As much as they have faced criticisms of elitism, there is something undeniably universal in their films. What this appeal is, it is hard to define. Perhaps it is simply that we all have that Coen feeling – that irreverent, bitter-sweet sensibility that represents an equal amount of respect for and mockery of life itself. And since we all have that Coen feeling, they must have it in spades.

What is your favorite Coens film?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

PhD Student in Culture, Film and Media at the University of Nottingham Blogger at [email protected]