Film Reviews

2016 has become the year where audiences are openly questioning the onslaught of mainstream movies coming out, especially when it comes to unnecessary sequels. Some of the films this year that have made us think ‘did this really need a sequel?’ include Now You See Me 2, The Hunstman, My Big Fat Greek Wedding 2, Independence Day 2, Zoolander 2 and even an Ice Age film set in space.

Richard Linklater may be the definitive coming-of-age filmmaker of our time, effortlessly blending John Hughes indebted stories of young people coming to grips with their own identities, with an Altman-esque ear for naturalistic dialogue. His films feel timeless, yet completely of their time – snapshots of a generation that will remain beloved when the next generation of cinephiles lay their eyes on them. A “Spiritual Sequel” His latest film, the punctuation-friendly Everybody Wants Some!!

You may be wondering why you are reading a review for a film initially slated for release in 2014, after its première at the Los Angeles film festival, in the here and now of 2016. It tells us a lot about contemporary cinema and the struggle independent films face in finding distribution that this well-made film has waited two years for a wider release when there have been countless lesser films clogging our screens in the intervening time. It has been with the recent support of Ava DuVernay’s company ARRAY that Echo Park has found a cinematic release in LA and New York as well as an international release through Netflix and, if you are looking for something different to the sometimes saccharine cuteness of US indie romances, I would encourage you to seek this film out.

The story of Freckles, written and directed by Denise Papas Meechan, opens with Lizzie introducing herself by voicing her strong hatred she has for the “ugly orange dots” that she refers to as her “star map to loneliness”. This is a story of a woman who has a disturbingly distorted view of herself. Despite her mother telling her that the freckles are “kisses from God”, Lizzie sees them as a curse.

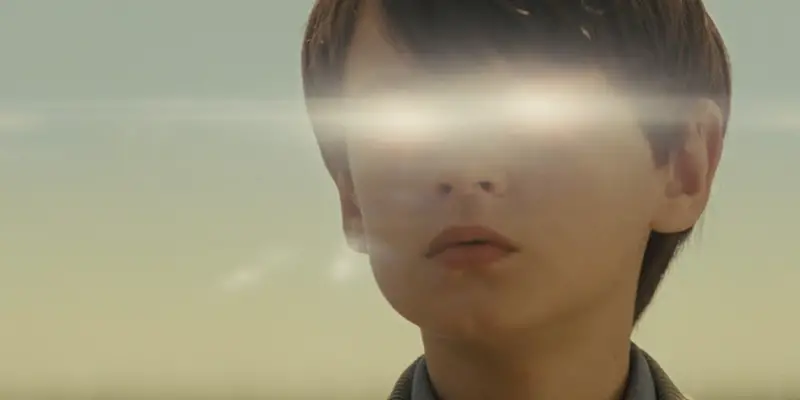

Film is the art of light. Paradoxically, light is that is the ultimate source required for life to exist, and is the greatest substance to cause horrific calamities. Fire was both a blessing and a curse for ancient civilizations to understand and attempt to harness, but it was quite often their undoing.

To talk about this film, you must talk about the rise and acceptance of post-modernist cinema with mainstream audiences and how this has changed the way modern genre films are tackled. To break it down, post-modernist cinema essentially is cinema that tackles ‘modern’ or traditional cinema. Post-modern cinema wants to actively point out the different film elements that make traditional cinema work, show them to you and deconstruct these cinematic codes in order to stand apart and comment on its established genre/story-telling methods that its currently indulging in.

Even in world cinema, the stories we see on screen are largely those depicting the lives and crises of the most well-off members of each respective society – showing situations that still can largely be referred to as “first world problems” without a sense of ironic bite. It is why a film like Dheepan is so urgently needed in the current, self-centred socio-political climate. It firmly puts us in the shoes of characters whose stories are never told in cinema:

With only four movies to his name so far, and with features ranging in genre from coming-of-age dramas (Mud) to quasi-science fiction (Take Shelter), Jeff Nichols’ films have at least one thing in common (other than that they all star Michael Shannon): they are all intimate productions, both in style and in their focus on the tight-knit relationships around us. Often set in the American South where Nichols himself grew up, his films deal with familial struggles and upsets in usually uneventful communities.

Action cinema is a pain to bring to light. Let’s be clear that every film is difficult to make and they all have inherent problems, ranging from little to gigantic nuances. But action takes the cake when it comes to painstakingly long hours and the mundane repetition that is required to capture the choreography of a scene just right.

Modern creatives have taken many liberties with the subject of vampire/werewolf lore. Films such as Blade and the Underworld series’ brought slick, Hong Kong-style hyper-violence wrapped in a trench coat, whereas Twilight added teenage brooding and sickly bubble gum romance, which many purists would rather see vanish into a sparkly haze. Emma Darks’ latest short Seize The Night fits categorically into the first grouping.