Debate: Propp’s Character Conventions In Modern Film

Rachael Sampson is a Northern screenwriter and critic based in…

Plot, visuals, and theme are all hugely important to great cinema, but movie audiences love characters, and they remain the most memorable aspect of many films. However, the same character types appear again and again in film – the heroes, the villains, the sidekicks and the damsels in distress. We simply accept this as a part of cinema, and of stories in general, and it’s because all stories follow the same narrative structure, according to Russian theorist Vladimir Propp.

Is depending upon character theories a good or bad thing for movies? Does it stifle creative freedom, or is it necessary to make an audience interested in the story? We can also ask, is Propp’s character template harmful to audiences? To answer these questions, we need to take a look at Propp’s theories in more detail.

Vladimir Propp’s Character Theory

In 1928, Propp said that all stories follow a narrative structure. To show his theory he broke down fairy tales into sections, and these sections reveal a sequence of narratives which nearly all films follow to this day. He said that after the initial situation is established, the tale takes a sequence of 31 functions. Alongside these functions, Propp devised a list of characters which are apparent in many narratives:

- The Villain: Struggles against the hero

- The Dispatcher: The character who makes the lack known and sends the hero off

- The Helper: Helps the hero in their quest

- The Princess (or Prize): The hero deserves her throughout the story but the villain prevents her from doing so. The journey often ends with the hero marrying the princess, thereby beating the villain

- The Donor: Prepares the hero or gives the hero some magical object

- The Hero: Reacts to the donor, weds the princess

- False Hero: Takes credit for the hero’s actions or tries to marry the princess

Harry Potter (2001-2011) – source: Warner Bros.

Sound familiar? This is a very apparent structure in films, from the classic era of Hollywood to the blockbusters of today. Look at the Harry Potter franchise for example. The Villain would be Voldemort, The Dispatcher and Donor is Dumbledore, The Helper(s) are Ron and Hermione. The Princess is Ginny, The False Hero would be Draco Malfoy and The Hero is Harry himself. One of the most popular movie franchises of all time, Harry Potter is built around these character codes.

But is this a good or bad thing?

The Debate: Sam Vs. Rachael

Sam Kelly

Movie audiences have always loved the familiar. While we crave and appreciate stories that challenge, surprise and subvert our expectations, we also get a weird thrill out of things happening exactly the way we think they are supposed to. It’s why a Bond film is a disappointment if there’s no “the name’s Bond”; or why a sports movie without an inspiring montage doesn’t feel right.

Some movie genres, like the Western or costume drama, are almost built on such tropes to the extent that we feel cheated if they don’t appear. Maybe this says something bad about cinema audiences, but it’s clearly a trend that exists, and it explains why Propp’s theory is so prevalent and important to film. We need a strong hero character to engage with and a villain to provide conflict and tension. Populating a film with Propp’s character roles means that the audience will immediately recognise the character’s purpose in the story, allowing the plot and characters to develop with more freedom.

Of course, not all films have to do this – in fact some of my favourites, like There Will Be Blood, have no definable character roles at all. And it could be argued that adhering to character roles stifles narrative freedom, forcing the writer into a pre-existing rigid structure. But filmmakers can be as creative and subversive with the character roles as they like, taking them in new directions with powerful effect on the audience.

For example, David Fincher’s The Social Network: is Mark Zuckerberg the hero, or is Eduardo Saverin? Is Sean Parker a helper, donor, false hero or villain? A case could be made for all of them. And the fluid shifting and blending between character roles can make for fascinating cinema while still grounding the audience in a structure they can easily understand.

Rachael Sampson

Propp’s theory of character roles is evidently something which a lot of writers and directors include in their movies, and it is undeniably a successful template to follow, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a harmful element in film. Since movies, television series, shows etc. strongly influence and shape the world around us, they can send harmful messages to the people watching.

For example, one of Propp’s character roles is the prize/princess role, a concept that infers the woman in the film is a reward for the heroes successful battle in conflict. Presenting women as prizes and inferring that they generally are not the ones to permit in conflict through demeaning stereotypes such as the “damsel in distress”, sends a dangerous message, especially to the younger generation. Due to this idea being evident in film long before Propp’s theory, we are stuck with a very predictable narrative.

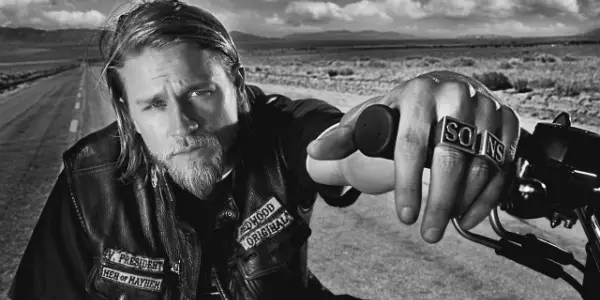

We have come a long way with films such as Frozen and television series such as Homeland, placing women into the limelight and allowing them to play more dominant and strong-willed characters – trying to break down those demeaning stereotypes previous films have displayed. However, this small change is still opposed with successful shows and movies that still abuse and portray women in a sexual manner, for example, Sons of Anarchy. In 2011, only 11% of protagonists in films were female.

Emphasising how glued filmmakers are to Propp’s ideology, and how harmful it can be to the viewers, transmitting an idea which tells women that they are to be prizes, highly sexualised and extremely attractive, and then on the other scale, these movies and series are suggesting to men that they have to be fighters and dominant figures.

Sam

The misrepresentation of women in film is certainly an important issue, but are Propp’s character roles to blame? His theory was taken from his research on Russian fairy tale. The Princess character is based on the fact that the role within the narrative – the prize, the thing that the hero aspires to and is blocked from due to the villain – is generally filled by female characters (often literally princesses) within fairy tales. This is a problem with fairy tales, but it doesn’t have to be a problem with cinema.

Laura Mulvey’s male gaze theory states that all media is viewed through the eyes of men and thus women are objectified by the gaze of the male director. I would argue that the objectification of women in cinema comes from the projection of this attitude onto character roles, rather than an inherent sexism in Propp’s theory. Although it is problematic that the Princess is the only explicitly gendered of the character types, this is a reflection of the stories of his time – I think if Propp wrote his theory today he would change the name to Prize, a more accurate description of the role which doesn’t rely on gender. And modern filmmakers should update his roles to reflect changing attitudes in society.

In fact, gender reversal of the Princess character has begun. The Hunger Games series, one of the only hit franchises with a female lead, sees a woman in the hero role and a man in the Princess role – in fact, Peeta Mellark’s character is so vulnerable and dependent on the hero that if he was a female character he would be rightly criticised as a damsel in distress.

Moving away from blockbuster cinema, 2013’s Philomena featured an elderly lady as the hero, with the Princess character being her long-lost son. It’s also possible to have a female Princess character that is unsexualised, developed and essential to the plot; think of Murph in Interstellar, a complex and important character who serves as the daughter rather than the lover of the hero, but is still clearly the Princess. These are positive signs in cinema, and a sign that character roles can be followed without objectifying women. It’s now up to filmmakers to use Propp’s character roles in progressive and intelligent ways.

Rachael

There has evidently been a change to cinema for women to be considered as the hero/protagonist in modern movies like The Hunger Games, and the role reversal idea through characters like Peeta Mellark, playing Propp’s prize/princess. However, there are only a small amount of films like this in comparison to huge blockbuster movie franchises that do follow these old fashioned character roles, such as; Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, Batman, the majority of Marvel movies, etc.But that is not the only way character roles can cause issues.

Referring back to the male gaze theory, as characters are viewed through the eyes of a heterosexual male, it sends very repetitive messages to the audience. It is the effect of these cinematic decisions from males in the industry (according to Laura Mulvey) which cause harm. Since media is the biggest transmitter of information, and on average a teenager is exposed to a staggering 10 hours and 45 minutes of media consumption a day, it really enforces the idea that we, as a society, should match the characters we see in fictional movies.

Men occupy 80 to 95+% of the top decision-making positions in American politics, business, the military, religion, media, culture, and entertainment. So if they have the majority of the control in these jobs, including the world of cinema, no wonder the younger generation are becoming more and more adapted to the subconscious messages they receive through TV and movie screens.

Men aspire to be Clark Kent, and women wish to be Lois Lane. It is bizarre how fiction, a limitless world where you can create a story with any possible outcome, for example, Superman flying around the world anti-clockwise to turn back time, is so restricted subconsciously, that we cannot break through stereotypes which ultimately harm people. The worst part of it being that we have aspirations to be like these characters due to the constant fuel from the media, a cycle which will be incredibly hard to break. And because we invest so much money into these movies, filmmakers will only repay audiences with similar messages since their profits infer we want to see more femme fatale and patriarchy.

Conclusion

It is clear that most narratives are told in a very predictable manner and they will be told like this for years to come, and since media such as films, adverts and propaganda are one of the biggest influences in enforcing ideologies, if not the biggest, Propp’s theory will continue to be an incredibly relevant feature in the world of film. It can be completely open to interpretation whether you think this theory is harmful or not, but society is however reshaping this theory by swapping stereotypical gender roles in film. It would be a huge breakthrough in the world of cinema if a filmmaker out there decided to fully challenge this theory and create a film that can only be described as purely unique.

What are your thoughts on the matter? Can you think of any films that challenge Vladimir Propp’s theory? Please share below!

(top image: The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey – source: Warner Bros. Pictures)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Rachael Sampson is a Northern screenwriter and critic based in London. Her latest film is currently in post production and she has 2 shorts cooking in the oven. Rachael is also a published short story author and theatre maker. She often finds herself daydreaming about Andrea Arnold's filmography and firmly believes that Inglourious Basterds is the greatest movie ever made.