COVER-UP: Seymour Hersh and the Search for Truth

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

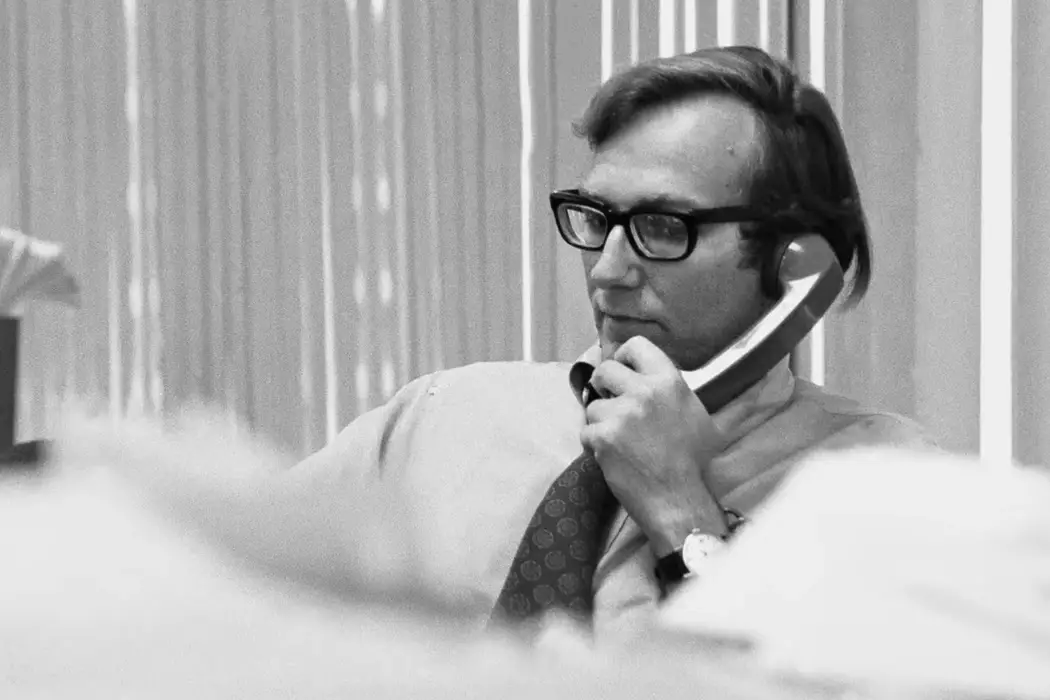

Acclaimed filmmaker Laura Poitras (Citizenfour, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed) first expressed her interest in making a documentary about Seymour Hersh’s career to the veteran investigative journalist twenty years ago. Hersh, still working at the ripe old age of 88, has doggedly pursued the truth behind U.S. government cover-ups for more than sixty years, breaking important stories ranging from the My Lai massacre in 1968 to the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in 2004. And while his work has not been without criticism and controversy, especially due to his reliance on anonymous sources, one thing is for certain: in a world descending deeper into the throes of fascism and “fake news,” with allies of the current administration taking control of major U.S. news networks, journalists like Hersh are critical to holding those in power accountable for their crimes.

A Culture of Violence

Perhaps that’s why Hersh finally agreed to work with Poitras on a documentary so many years after her initial request: because the need for other investigative journalists like him to step forward and do the work is quite possibly more important than ever. It’s hard work, and dangerous, but all the more necessary because of that. As Hersh notes in Cover-Up, co-directed by Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, “We’re a culture of enormous violence. You can’t have a country that does it and looks the other way.” In Hersh’s view, the press is not subject to censorship so much as self-censorship; they’re all too aware that things are being covered up, but they don’t bother to dig any deeper, too afraid of pissing off the powers that be. (One cannot say the same about Hersh, repeatedly described as a “son of a bitch” in taped conversations between Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger that are featured in the film.)

Hersh opened his extensive personal archives to Poitras and Obenhaus during the making of Cover-Up, which results in some on-screen drama when he accuses the filmmakers of potentially jeopardizing the identities of the anonymous sources inside various government agencies whom he has relied on over the years. (Only those who have already revealed themselves or passed away are identified by name in Cover-Up.) At one point, when the filmmakers try to put a certain document on camera, he blows up and declares the shoot over. Needless to say, his personality is on the prickly side, albeit also charismatic, engaging, and legitimately quite funny; it’s easy to see why so many sources who Hersh claims actually hated him would choose to talk to him anyway…especially when doing so likely helped ease their consciences about the morally questionable work they were engaged in.

An Empire of Lies

Cover-Up doesn’t delve too deep into Hersh’s personal life, though it does touch on how growing up in a home where not much was ever talked about—including how his Jewish father fled Eastern Europe to escape persecution—helped ignite Hersh’s fascination with revealing the truth hidden behind the facades put up in so many aspects of life in the United States. The film also acknowledges the emotional toll that this kind of investigative work can have, especially when uncovering atrocities; Hersh recalls being almost too overwhelmed to go on after seeing horrifying photos of murdered babies at My Lai that reminded him of his own young child, and needing his wife (psychologist Elizabeth Sarah Klein, who he has been married to since 1964) to provide reassurance and support. Naturally, a film about digging up dirt on disturbing conspiracies and crimes includes a substantial amount of disturbing imagery as well, though, like Hersh, we would do well to not look away simply because of our own discomfort.

While Cover-Up is not the most visually engaging documentary, it makes up for its lack of creative presentation with absolutely riveting content. The film devotes the most screen time to the My Lai massacre and Hersh’s exposure of the vast conspiracy to cover up it and other war crimes committed by U.S. troops in Vietnam. Hersh, who at that time had recently left the Associated Press to become an independent journalist, recalls flying back and forth across the country, visiting military bases where soldiers were being hidden from public view and small towns where soldiers had come home bearing the weight of what they had done; one mother told him, “I gave them a good boy and they sent back a murderer.” Much like the reports decryed as “fake news” and “witch hunts” by the current administration, his articles were originally dismissed by the U.S. government as anti-patriotic propaganda, but eventually confirmed as all too accurate.

Hersh parlayed this monumental scoop into a role at The New York Times, where he investigated everything from Watergate to the CIA’s illegal surveillance of U.S. citizens before falling out of favor with his editors when he decided to investigate major corporations, which hit too close to home for the self-styled paper of record. It’s his post-Times era that comes under the most scrutiny in Cover-Up, including high-profile missteps such as when he almost utilized forged documents in his book about the Kennedy administration and mistakenly alleged that Syrian rebel forces, rather than the Assad government, had used sarin gas on civilians. In recalling these moments on camera, Hersh gruffly notes that this part of the documentary is much less fun for him. Nonetheless, it’s important that Cover-Up doesn’t shy away from holding him accountable, much as he has the U.S. government over the course of his career; it reminds us that the point of it all is not just to laud an individual’s achievements but highlight the importance of truth above all else, even one’s personal reputation.

Conclusion

Cover-Up is about much more than just one man’s lifelong search for the truth; it’s a film about the importance of constantly interrogating those in power, and refusing to accept the narratives they tell us without looking beneath the surface to see what rot they’re trying to hide. In any other year, it would be an important documentary; in 2025, it is essential.

Cover-Up opens at Film Forum in New York on December 19, 2025, before being released on Netflix on December 26, 2025.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. In addition to movies, she's also a big fan of soccer, BTS, and her two cats.