Po-Chih Leong’s PING PONG: An Examination Of Language & Identity

Rose is a freelance film critic who has written for…

Ping Pong (1986) directed by Po-Chih Leong is a Cantonese and English-language comedy-drama that questions and challenges aspects of the Chinese diaspora in Britain; what it means to be Chinese, and how language is seen as an integral part of that Chinese identity, which is both rejected or accepted by various characters throughout the film.

Centred around a Chinese-British lawyer-in-training, Elaine Choi (Lucy Sheen) is asked to enact the will of prominent Chinatown restaurateur Sam Wong, whose disparate and complex family resist her efforts at every turn. There is a significant generational difference in the identity and acceptance of the Chinese culture between the characters of the film. The complex nature of Chinese identity itself is also examined – it is not as simple as a singular identity across the Chinese diaspora in Britain. Rather, it’s a multitude of different relationships with the homeland that all combine to make this a significant, if under-appreciated, British film.

Elaine Choi: Identity Under Attack

Elaine’s relationship to her Chinese heritage is a complex one. While she sees herself as Chinese-British, a first-generation immigrant who moved over at a young age, adapted to living in Britain, with a strong London accent, others dismiss her identity due to her inability to speak Cantonese.

Her employment by Sam Wong is due to the fact she has helped another member of the family previously with regards to a stolen watch, and it is this experience, rather than her Chinese heritage, that has led the dead restauranteur to choose her as the executor of his will. Initially confused by this, asked to relay the contents of a will she “can’t even read”, Elaine makes her way into London’s Chinatown to meet the family.

The large and complex Wong family all appear to have had difficult relationships with the former patriarch, not least among them his eldest son Mike, who refuses to go to any of the ceremonies once he learns his father is dead. One of the family’s issues is with the choice of Elaine as executor, as Cherry – Sam’s daughter from another marriage — tells her later in the film that they would prefer “someone older… more experienced… [who knows] Chinatown better”.

When Elaine states that the will specifically asked for her, having had it translated from the Cantonese to English by her uncle, Cherry replies that Elaine is a “stranger in Chinatown” who does not understand the “shops, restaurants [or] people”. Elaine’s inability to speak Cantonese fluently to the family only serves to reinforce her position as an outsider, someone who has lost her own Chinese identity.

In his book Cinema Babel, Abé Mark Nornes states that once a character crosses “the linguistic barriers, they are marked as foreign”[1], and in Ping Pong it is Elaine’s stilted and awkward Cantonese that marks her as a foreigner within her own community, someone who in the eyes of the Wong family has rejected her Chinese heritage. This is something that Lucy Sheen, who played Elaine, her debut film role, has also commented on in recent years, specifically in a talk given at the University of Westminster with her Ping Pong co-star David Yip.

When asked about the depictions of the Chinese-British community on screen, Sheen replied that Elaine’s position at the beginning of the film is someone who “classifies herself as somebody who’s Chinese, again who isn’t really Chinese [in the eyes of the Chinatown community], who hasn’t really thought about her heritage to a certain extent”.[2]

There are also more explicit references to Elaine’s supposed lack of Chinese identity throughout the film, both by various members of the Wong family as well as Elaine’s uncle. She is frequently referred to as a ‘gwei-mui’ – explained to Elaine and the audience within the film by her uncle as meaning ‘foreign woman’ – furthering the concept of Elaine’s outsider status within the Chinese diaspora community in Chinatown.

In An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking Hamid Naficy states that language not only shapes “individual identity” but also “regional and national identities prior to displacement”[3]; Elaine has become so assimilated – in the eyes of some of the characters in the film – with British and English culture through her lack of Sinophone speech, that she has lost her identity as a Chinese-British woman.

This positioning of Elaine as a foreigner in her own community serves to negate her own experiences as a first-generation immigrant who, according to her uncle, “spoke not a word of English”, rejecting her experience as a Chinese-British woman who lives outside the safety and comfort of London’s Chinatown.

Mike Wong: Diaspora Anxiety

David A. Jasen and Pramod K. Nayar, in their guide to postcolonialism, speak of the diaspora anxiety that can emerge between different generations of a diaspora community and the complex issues that surround the concept of assimilation into the host community versus the preservation of identity, which is often a deeply personal issue.

This idea of “identities in process” and the “[negotiation] between an inherited identity and… a new one in the adopted space, country and culture”[4] is one of the key themes within Ping Pong as the struggle between tradition, inheritance and the desire to have a sense of individuality, beyond the confines of the community.

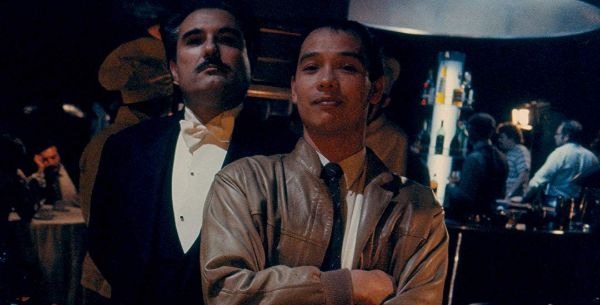

This anxiety is explored in Ping Pong through the narrative journeys of the two younger Wong brothers, whose paths in life have taken them away from the traditions and confines of Chinatown into the wider society. Mike Wong (David Yip) has followed his father in the restaurant tradition, but rather than working within the family’s business, he has moved out of Chinatown and away from any aspect of his ‘Chinese-ness’. His prestigious new restaurant where the staff communicates in Italian rather than Cantonese and where fancy desserts are a key item of the menu is a world away from Sam Wong’s restaurant in Chinatown.

Mike’s deliberate use of Italian not only serves to reinforce the perceptions of a high-class establishment but also reflects the European language as “prestigious… imbued with Western dominance”,[5] unlike the Cantonese that he has rejected. Although Italian is not the language of the former empire of Britain, it acts as the “colonial language [that] becomes culturally more powerful”,[6]. Mike perceives it as a form of social capital superior to his first (neglected) language of Cantonese and his heritage in Chinatown.

Sam’s will states that Mike will only receive ownership of the business if he continues to run in the same, traditional way it has always operated, without any changes or alterations to the menu. The tension that has grown between two men stems from Sam’s refusal to adapt to the Western conventions that Mike has accepted, with the younger man relaying the story of his father asking for chopsticks the first time he visited his restaurant as a way of highlighting to Elaine the difficult relationship he has with his father.

However, even when Mike revisits Chinatown and reunites with his mother he still refuses to speak in his first language with her, despite the fact it would be considerably more convenient. Instead, she replies to him in stilted and hesitant English. Mrs Wong, in retaliation decides to speak through Elaine, giving commands in Cantonese for Elaine to translate – a complex and unnecessary arrangement that only occurs due to Mike’s complicated relationship with his first language and the implications that it has for his own perceptions of his identity.

Navigating Wealth and Race: Mike Wong’s “Ideal Gentleman”

Po-Chih Leong draws on aspects from his own middle-class upbringing as stated by David Yip that he (as Mike Wong) is essentially playing the part of Leong[7]– with characters that are British-Chinese second-generation immigrants who were afforded significant wealth and privilege, such as the Wong boys’ private education and boarding school.

This is important in terms of the construction of identity for the two young men, who are each faced with a form of alienation from their Chinese heritage – Mike’s is a self-imposed distance based on misplaced assumptions of superiority, whereas Alan’s seems to stem from his decision to marry a white woman, which appears to alienate members of his family.

Mike’s issues with identity are explored in detail within the film through the use of a flashback in which Mike describes to Elaine his first encounter with an Englishman. Mike is introduced to high society – given his first taste of wine and has an impression of English identity that he wishes to emulate.

During this scene, it is shown that the young Mike speaks exclusively in Cantonese and the Englishman comments on this and says “you can’t understand a word I say” as if it were a form of amusement. This perception of English identity and how it is explored in Ping Pong is also furthered by the appearance of Mike’s school friends. They are the caricatured example of public schoolboys: loud, obnoxious and fans of making a mess of restaurants.

It is even remarked to Elaine by one of the men that Mike has become “corrupted… to the very model of an English gentleman”. The use of ‘corrupted’ to describe Mike’s transition implies that it is an unnatural turn of events, that Mike’s created English identity has somehow ruined his Chinese heritage.

This complex relationship that both Wong brothers hold with their perceptions of identity is continued during a scene in which Elaine and Mike visit Alan and his wife Maggie to talk about the will. The house is starkly different to the Wong’s family home, with little to no trace of Chinese culture, unlike the art that decorated the walls of the Wong house. However, the most important aspect of this scene is that neither Alan nor Mike chose to speak in their first language to each other, instead they both speak English.

While Cantonese was their first language, like Elaine their ability to speak it has faded over time through lack of use, and now they feel most comfortable expressing themselves in English. To speak in English is to fit into wider society and to have an identity that is perhaps more acceptable in the minds of the second generation of Chinese British immigrants. For the two Wong brothers, this preference to use English as a primary form of communication signifies an aspect of removal from their Cantonese heritage.

Identity and the State in Ping Pong

One important aspect of the theme of identity in Ping Pong is the exploration of the complex intersections between ‘official’ Chinese identity of the one-state policy. This includes the various states and territories that make up the larger Chinese nation that do not see themselves as complying with the governmental policy and also identity themselves from Beijing.

This rejection of a monolithic Chinese identity is most prevalent in the scene involving Elaine and a Chinese embassy official as she tries to sort out the paperwork to send Sam Wong’s body back to China. On Elaine’s entry, she asks the official in English about the process of sending to body, to which the official replies in Mandarin “Can you repeat [the question]”.

His immediate and incorrect assumption is that Elaine understands and can speak the official language of China, and when she replies asking about “Capital Radio?” – as she has not understood the question – it is his turn to be confused. Finally, Elaine admits in stilted Cantonese that she does not understand Mandarin and the official switches into English.

This conversation of codeswitching not only highlights how the standard language for conversing in the Chinese embassy is Mandarin, but also how Elaine’s inability to speak a Chinese language immediately places the embassy official in an antagonistic position towards her as he refuses to speak English to her when she has clearly initiated the conversation in that language.

This antagonistic relationship between the two characters continues as the official states that Elaine should “learn [her] Chinese language” when her inability to speak Cantonese fluently is established as a way of connecting with her “homeland”. Elaine sarcastically replies to this by saying “which one?”, showing that despite the disapproval of the official, she feels dually connected to two separate homelands and this duality is not negated by the fact she cannot speak fluent Cantonese.

Within Ping Pong, there is also reference to the complex nature of Chinese identity outside of the boundaries of language, of how the nature of the monolithic nation-state is not one that all the characters that belong to the diaspora subscribe to. When asked about her father by the official, Elaine states that he was buried in Macau, which is “very close to China”.

A former Portuguese territory until 1999, Macau is currently classed as an autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China, but during the production of Ping Pong and up to its release in 1986, there would have been significant awareness of Macau and its relation to China due to the Sino-Portuguese Joint Declaration that is signed in April 1987 which stated “China will assume sovereignty over Macau on 20th December 1999”.

Prior to this, Macau had been designated a “Chinese territory under temporary Portuguese administration”[8], which lends itself to the idea that Chinese diaspora identity is nothing as simple as a shared language, but rather it is a complicated intersection of place, space, and self-identification.

Ping Pong is a film about the struggle to find and maintain your own identity in a world that is so desperately trying to place you in a specific box. Po-Chih Leong manages to craft a tale that’s universal while still being set around the hyper-specific world of London’s Chinatown. It tackles the complexities of identities of second-generation immigrants in 1980s Britain, as well as the restrictions that state institutions try to impose on citizens’ own perception of identity.

[1] Abé Mark Nornes, Cinema Babel. Translating Global Cinema (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2007) p.7

[2] ‘China in Britain #1 Film – Actors Lucy Sheen and David Yip in conversation about Ping Pong (1986)’ <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPeIG0ocky0>[Accessed 3rd May 2018]

[3] Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2001) p.24

[4] David A. Jasen, and Pramod K. Nayar, Guides for the Perplexed: Postcolonialism (London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2010) p.166

[5] Gemma King, ‘The Power of the Treacherous Interpreter: Multilingualism in Jacques Audiard’s Un Prophete’, Linguistica Antverpiensia 13 (2014) pp.78-92 (p.82)

[6] Robert J. C. Young, Postcolonialism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p.140

[7] ‘China in Britain #1 Film – Actors Lucy Sheen and David Yip in conversation about Ping Pong (1986)’ <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPeIG0ocky0> [Accessed 3rd May 2018]

[8] John Bowman, Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture (Columbia: Columbia University Press, 2000) p.248

Have you seen Ping Pong? Is it something you’d consider searching out on the BFI Player? Let us know in the comments!

Ping Pong was originally released in the U.S. on July 17th, 1986.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Rose is a freelance film critic who has written for Little White Lies, Screen Queens and Film Daze. She loves thrillers, great female characters, Al Pacino, and multilingual cinema.