The Existentialist Wears Velvet: A Celebration Of PURPLE RAIN

John Stanford Owen received his MFA from Southern Illinois University,…

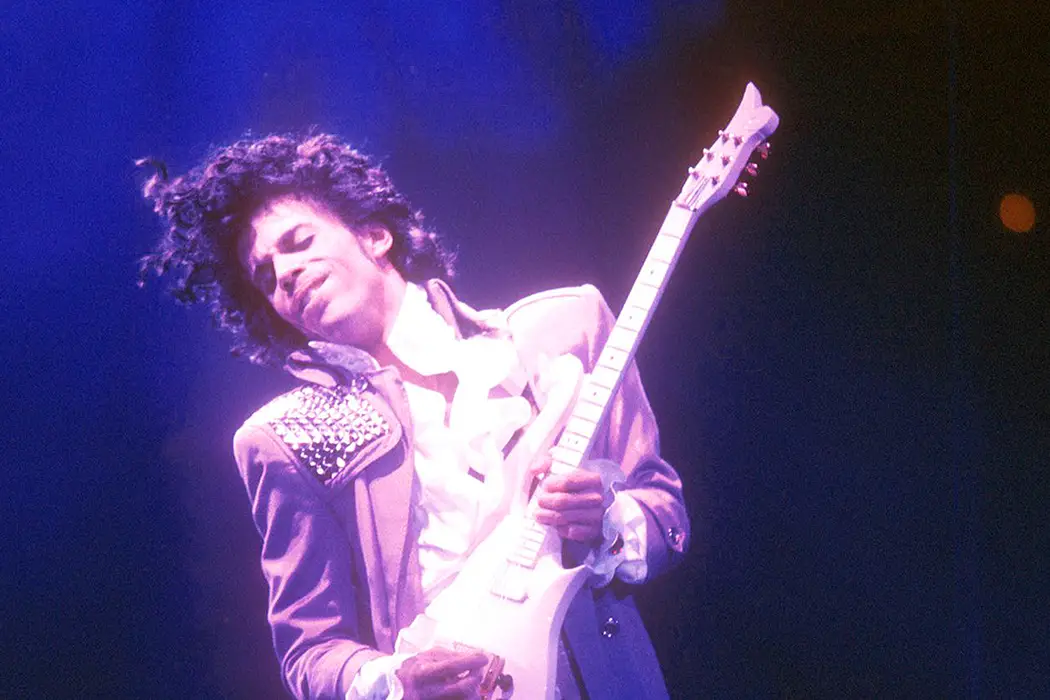

Prince Rogers Nelson never fell prey to the novelty trap. His theatrical mystique—the leather and velvet, the bug-eyed sunglasses, the high wall of curls suspended inside an impenetrable resin—might have led critics to dismiss the artist as another glitter-bombed R&B pop star, long on glamorous image, short on artistic integrity. Yet, even with the harlequin persona, Prince’s work superseded the flamboyant facade. And for that, Purple Rain, both as an album and as a film, deserves chief credit.

With little thematic cohesion, the subject matter examines a kaleidoscope of human conditions. In both musical and cinematic renditions, Purple Rain’s song list teems with heavy questions about life after death, the aloof coldness of family drama, spontaneous sex with femme fatale strangers, and as if it were the most out-of-reach subject, finding dedicated and dependable love. The topics tackled seem disjunctive at a glance, but the narratives wield real, unapologetic candor, baldly showing what it means to think and suffer and laugh and toil and dwell and experience frustration, grief, elation, and boredom.

A Double Legacy

While the multi-instrumentalist had reached maestro status before Purple Rain hit shelves, the album catapulted his act onto the international stage, cementing him as a commercial and critical success, and in this way, it stands as the centerpiece of a celebrated discography. Which leads to the question: how does Purple Rain the film coincide with the record’s legacy?

They function as two integral halves of an artistic system, sharing not only a name, but also the same erratic tonal structure—in both presentations, a cavalcade of human emotions and experiences receive some form of exploration. In one scene, director Albert Magnoli shows raw, horrifying domestic violence and in another chapter an Abbott and Costello-style gag occurs. Its narrative splits into equal parts elated and elegiac, glorious and grim, and if the film’s mood is sprawling, so were the reactions. Responses range from declarations of cinematic transcendence to lamentations of the movie as an atrocious, laughable disasterpiece. But no matter which side of the critical aisle one falls on, nobody denies that Purple Rain asks questions other motion pictures are afraid to.

“Why do I need this person so much?”

“Why does this hurt so bad?”

“What pain am I willing to inflict to get what I want?”

No one can assert, at least not in any reasonable fashion, that the album serves only as the movie’s soundtrack, nor can one claim the film came to fruition solely as a ploy to buoy record sales. But surely the movie risked becoming a vehicle for stationing Prince higher on the billboard charts instead of existing as an independent work of art. While those may have been effects, they were never the singular intention.

Purple Rain the film had to break heightened boundaries to become something other than a media extension, and so Magnoli and Prince refused to play it safe, forgoing the making of a passable and studio-friendly film in favor of creating a memorable and vulnerable one. After all, here we have a script that includes childish pranks involving skinny dipping dares alongside musical acts featuring performers donned in leopard print. In this universe, people walk around in skin-choking corsets worn with the casualness of long-worn, threadbare pajamas.

Therein lies the reason for the film’s installation inside the pop culture museum of treasures: it stays with you, a thought that never intrudes, but lingers for years as a recurring visual implant. The film is, in effect, a mirror reflection of Prince himself. In fact, read one paragraph of his biography and it becomes clear that the line between the musician and the character he plays is not so much blurred as it is intertwined.

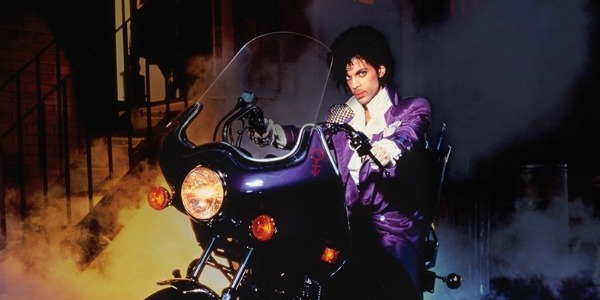

The Purple Persona

The movie, in some ways, is about reconciliation—the mending of connections between husband and wife, father and son, romance and ambition, change and destiny, and most of all, image and ability. That last conflict is by far the most Prince-esque element. In specific terms, the extravagance of his persona and the depth of his music did not always coalesce.

Did it have to be that way? Probably, yes. And here are some particulars. I imagine that somewhere out there a brilliant musician works a thankless, tedious call center job. When customers call with complaints about their bill, they treat her humanity as an inconvenience, and all the while no one will know that the person who wears that headset can vocalize and play the piano in a way that moves the most jaded listeners. No record executive will discover her, because the garish image remains absent. There are no sequins or bold hairstyles or acrobatic dance moves. She will always be a person, and only a person, not a musician, much less a star.

As he shopped his music around, did Prince know record executives required something wholly separate from virtuosity? I think he was aware. It is as though he used the vibrantly colored clothing, ruffled ascots, head bands, and platform shoes to lure an audience who came for the theater, at first, but stayed for the transcendence of music. After all, the thought of Prince wearing sweatpants and slurping cereal milk feels downright absurd.

In the movie, the person-versus-self conflict that stands in the narrative spotlight dives deeper, squeezing past superficial image toward authentic identity. In other words, while Prince’s character (known by the clandestine moniker “the Kid”) presents a purple-velvet persona to reach a wider audience, he also seeks reconstruction of self. His off-stage personhood, that is. One of Purple Rain’s most pressing questions is this: “are we resigned to repeat the past over and over and over?” The question is asked through the looming father, a human portrait of toxicity and misdirected anger.

Spliced between performances that place this picture as a paragon of rock and roll films, is terrifying domestic violence. Our hero lives at home, not necessarily because his music career doesn’t pay the bills, but because his father beats his mother, and someone has to be there to literally and figuratively cushion the attacks. The director uses zero exposition in this narrative arc—when you see mom bleeding on the sidewalk, the reasons behind her son’s living situation require no explanation.

His presence provides the only demarcation line dividing his father’s rage and his mother’s demise. And despite his desire to deflect a recurring legacy of violence and terror, Prince’s character also proves plenty capable of descending to the bleakest caverns of human behavior. At this point—and perhaps only at this point—his cinematic twin and his actual person diverge. And that’s where “Purple Rain,” in its third vessel as single song, enters the narrative: a ballad of regret for the preventable wrongs that turn bright hopes to persisting bitterness. “I never meant to cause you any sorrow. I never meant to cause you any pain. I only wanted one time to see you laughing. I only want to see you laughing in the purple rain,” Prince croons with an elegiac, pleading sadness that breaks the template of radio-friendly pop diddies.

The song opens the penultimate scene in a film that, at this point, had ferried viewers across an emotional tempest, pushing the story toward closure as Prince’s character seeks redemption for a list of follies, his father’s and his own. True to form, the tone shifts once again, ending on a sunnier note after the crowd erupts and the artist returns for an encore performance of the synth-laden, dance track “I Would Die 4 U.” In both performances, the film asks yet another set of existential questions.

“How much do words matter?”

“Can language conjure forgiveness?”

“And what about redemption?”

The Existentialist Exits

It seems important to note the root of existential is exist, to travel about in a conscious body. Which Prince no longer does. The world shines brighter for his having been a part of it, and not only in light of the contributions he made to music and cinema, and not because of the multiplying list of private charitable contributions that became public after his passing. Prince left us with a looking glass with which to examine our own behavior.

There exists little to no disagreement about the virtuoso’s unparalleled talent in the studio and on stage. The way he commanded multiple instruments with a balanced dose of electrifying aggression and graceful finesse—that showmanship puts up the highest bar of competition. Yet, his legacy moves beyond even his gifts as a music maker. You will not find recordings of Prince Nelson Rogers touting his charitable endeavors. Until his death in April 2016, a long list of human kindnesses happened without attribution. Examples include millions of dollars donated to schools and community programs, paying for the installation of solar panels, establishing coding training provided for underprivileged youngsters, and the funding of libraries in impoverished neighborhoods. The anonymity came at Prince’s request, and only after his body became ashes did this information become public.

Of course, very few people have deep enough pockets to keep libraries open or shorten the path toward the elimination of fossil fuels. Despite his artistic skill sets, it seems he knew that, any time a person makes a living off their art, luck factors into the equation at least somewhat. And that’s where his true legacy resides. In other words, the art Prince made gave his audience an antidote for the poison of apathy and malintent. It shows us how to divert crisis without the financial and influential power so few people wield: be consciously, actively, thoughtfully, consistently human.

The existential questions asked in Purple Rain never receive answers. Instead, the film asks them quite pointedly, as a task for the viewer to conquer. And that’s the point: it’s up to us to behave in a way that does no harm to others.

Dearly beloved, we have gathered here today to get through this thing called life. These words open the album Purple Rain, a choice that is in no way arbitrary. How bizarre to think that such a loaded introduction leads to an uptempo dance track (“Let’s Go Crazy”). At the end of the day, we dance to make human strife ricochet from our lives. Humanity means to connect through the inevitability of suffering, an unfortunate fact against which we only have one line of self-defense. Let’s not cause any more pain than what is already unpreventable. Those are Prince’s final words on the matter. If that’s not the recipe for an impactful legacy, I do not know what is.

What is your favorite Prince moment?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

John Stanford Owen received his MFA from Southern Illinois University, where he also taught English courses. When JSO is not penning reviews and essays on cinema, he's reading and writing poetry, walking with his dog, or dancing to Radiohead.