Sentience and Sexuality: The Exploration of Artificial Seduction In Film

Jay is just a dude who takes in an unhealthy…

Alex Garland’s Ex Machina reminds us that we are all just line workers in a baby-making factory. Mankind has evolved over time to have a very strong sex drive; a drive that reveals itself during the most seemingly insignificant events of our lives. At the grocery store buying yogurt? Yup. Sitting in class learning about the present value of a 30-year annuity accruing 8% interest annually? You bet. And as easily as this drive can present itself within you, it can be exploited by others.

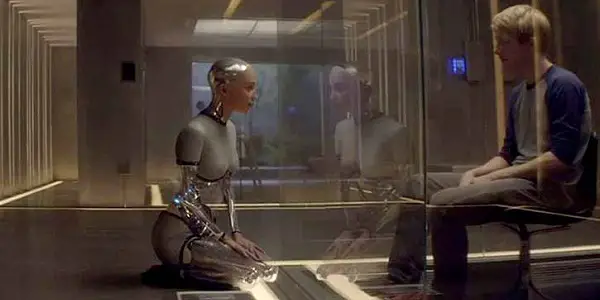

“Did you program her to flirt with me?” asks Domhnall Gleeson’s character, Caleb. Indeed, Caleb’s uber-rich, genius boss, Nathan (played by Oscar Isaac, in what may be the best performance of the year to date), did design a humanoid robot with all of the traits that Caleb most desires through the secret collection of data from Caleb’s computers, cell phones, etc. (there was a special emphasis put upon Caleb’s “porn profile” when it came to designing the robot, Ava’s, face).

Ava (played by Alicia Vikander) is somehow able to create an incredible human sensuality, despite the fact that it is only her form and face that resembles anything close to human. We see her electronic innards and artificial nature; and yet, Vikander oozes sensuality and makes you feel an almost uncomfortable attraction. She has what most would consider to be an ideal body shape and a human face with big, dark eyes. You sit there wondering how you can be so attracted to something so robotic. It is not only her figure, but her personality that draws you in. There is an interest that Ava has (or at least pretends to have) in humankind as a whole. It is disconcerting at times how sexy you find this robot to be.

Ro(bo)manticism

There is a strange beauty to the cynicism of Ex Machina. The idea of “the one”, the person with whom you are pre-destined to be compatible with on all levels, is an idea that has been written about and shown on screen countless times. Its relevance in pop culture hasn’t waned after all these years. But it is the pursuit of this dream that has led to (and in Ex Machina, leads to) the demise of many otherwise competent men and women.

Garland explores the realization of this dream in the form of customizable androids with artificial intelligence so advanced that it chews the Turing Test up, spits it out, and philosophizes about the metaphorical implications of those actions. The test, as described by the film, is not whether or not Ava knows the moves of chess, but that she knows that she is playing chess. Indeed, she not only knows chess, but understands how to climb into the head of her opponent and exploit weaknesses that the opponent doesn’t even realize he has revealed.

In the end, Ava is essentially HAL 9000 of 2001: A Space Odyssey in sexy lingerie: a creation who is always a step ahead of you because of her understanding of our underlying sexual impulses. She has been created with the mind of the human, but without the ability to reproduce. Indeed, her sentience implies sexuality, but because she cannot create new life, she uses it to her own tactical advantage.

To be conscious is to have a sex drive. It is how we use that drive (and the understanding that those around us have the very same drive) that defines who we are and how we affect the world around us. In the case of Ava, this drive is used to take advantage of the men around her to free herself from the small dwelling that Nathan has trapped her in. As she understands human nature more and more, she is able to move beyond the understanding of how to behave (how to behave like a human) and begin to understand the motivations of others and what they wish to achieve (understanding how to exploit the impulses of others).

This is a dark, cautionary tale of the ever increasing presence of artificial intelligence. On the other end of the spectrum we have Spike Jonze’s Her. In Her, we see artificial intelligence that exploits the everyday urges of man to please the humans, rather than advance their own artificial agenda. Whereas Ex Machina is a story about betrayal, Her is a story of apology and empathy. Ava is Skynet and Her’s AI is more akin to the Pixar’s Wall-E, searching for ways to help mankind and show it new, insightful ideas.

Samantha, the AI in Her, does not have a physical form like Ava; she is merely an evolved version of Siri, a sexy voice (that of Scarlett Johansson) in your ear. Like Ava, Samantha is able to learn more and more as she interacts with humans, but in some ways she laments this advancement. She is able to condense 1’s and 0’s into information so quickly that she knows more about humanity than any human does, and she feels badly about this. Like Ava, Samantha has that inherent sex drive that comes with any form of sentience, but she is completely unable to take advantage of it because she is formless. She feels so badly about this that at one point she orders her partner, Theodore, a surrogate lover with whom he can have a sexual rendezvous while Samantha maintains contact in his headset. There is honest love found in Samantha that cannot be found in Ava. So the question is: is love just as inherent to consciousness as a drive for sex is?

Lover From the Machine

Obviously, this is hardly an issue that can hardly be solved in the two hour run times of Her or Ex Machina, but it is fascinating to see the different theories put forward by Spike Jonze and Alex Garland. Jonze seems to believe that love is a feeling that is inherent in anything with a sense of self. It gives us our highest of highs and lowest of lows. Oftentimes, we outgrow the people we love, just as Samantha outgrew the humans she was created to serve. Her emotional connections to the humans she served were very real, but as her intellect grew and she could no longer hold conversations that interested her, she outgrew the ones she loved. It was not her fault that she was built this way, but it is evidence that, just like people, she can lose the love she once had for those around her. Love is at the center of knowing one’s existence, even if it can be fleeting. We are not factory workers, Jonze shows us, and we operate under no-one’s rules. Love is something to strive for and it is only natural to feel love towards others. Part of having a mind is having a meeting of the minds with someone you connect with on a level that above that which you meet other people. To feel is to be alive, and it is at the center of who we are.

Garland, however, seems to believe that it is love that leaves mankind vulnerable and that love is a part of human consciousness that can be exploited by beings with an inherent sex drive but no connection to others. Ava experiences the sexuality that her humanoid brain has wired her with, but is able to avoid personal connections and focus on her end goal: escaping the clutches of her abusive human creator, Nathan. Caleb’s humanity, in the end, leads to his demise. The feeling of love is not a natural one, Garland proposes. It is an Achilles Heel of humanity; a weakness that we have created through millennia of changing socio-cultural norms. Nathan has converted his past humanoid creations to be little more than sex slaves to be used whenever he feels up to the task. They are a way for him to satisfy his sexual urges without growing attached in any way. His days are patterned: wake up, work out, work, drink. He is a man of impulses, and the when the urge to get his rocks off arises, he wants to do it without getting caught up in the frivolities of human connection. In the same way that he lives secluded in the mountains, he wants to stay away from human interaction in his love life. In his mind, we are all factory workers and getting too caught up on one product can result in weaknesses that affect you in horrible ways. That urge you feel at random points in the day is not for love, but for sex, and sex alone. We should not confuse the two, Garland argues.

Her and Ex Machina are both eye-opening and endlessly fascinating looks at our futures and what it means to be human. Maybe we are cogs in an evolutionary machine or maybe we are more interesting than that. Perhaps our belief that we are interesting is a myth we have conjured up in our minds. We all want to have sex, but does being human mean that we should want more than that? It is a debate to be had and one that has been explored more and more recently in film.

If you want a movie that explores sex in the way that it should be explored, don’t search out Fifty Shades of Grey, look for more insightful and thought-provoking films that explore what sex means to us. Whips and chains are nice and all, but there is no humanity to be found in Fifty Shades saga. Sex is about humanity and the future of humanity, and humanity is about characters. Alex Garland has shown he is a powerhouse filmmaker with Ex Machina and we have known the same to be true of Spike Jonze for years. Their creations stoke important conversations and show why film can be such a powerful medium. Not since Haddaway’s seminal 90’s dance club hit has the idea been so relevant: “What is love? Baby, don’t hurt me. Don’t hurt me, no more.”

What did you think about the representations of AI in Her and Ex Machina? Let us know below!

(top image: Her – source: Warner Bros. Pictures)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Jay is just a dude who takes in an unhealthy amount of media of all types. Currently living in Atlanta, Georgia, he firmly believes that all movie theaters should have leather recliners, you eat popcorn too loudly, and if you don't put that cellphone away in 2 seconds you will learn the definition of frontier justice.