documentary

Ava DuVernay returns to the documentary format with 13th, a look at the amendment of the United States Constitution that simultaneously abolished slavery and established a loophole for denying rights to targeted groups. The troubling wording in the amendment has to do with convicted criminals, who are the only people exempt from the abolishment of slavery and involuntary servitude. That exemption, while small at the time, has snowballed into a huge issue thanks to America’s system of mass incarceration.

Coming Out is the personal story of young filmmaker Alden Peters. The film follows his coming out process as he tells his parents, friends and siblings how he has repressed his sexuality for a number of years. In using a homemade video style of filming, Coming Out gives us an insight into not only Peters’ journey but into his mindset as he starts to immerse himself into the 2016 LGBTQ lifestyle.

The sincerity of The Homestretch is certainly never in doubt. Depicting the plight of three homeless teens in Chicago, Anne de Mare and Kirsten Kelly’s documentary interweaves the personal stories with various facts and statistics highlighting the widespread nature of the issue. Unfortunately, despite its pure intentions, The Homestretch never really manages to succeed to be truly engaging, regardless of the clear warmth of the three featured youths.

First published in 2000 under the pseudonymn JT LeRoy by author Laura Albert, “Sarah” became a transgressive fiction literary sensation. After holding court with such seminal writers of the sub-genre such as Bruce Benderson and Dennis Cooper, the rising writer of American letters seemed destined for superstardom. Whisked away on the coattails of celebrities impressed with her abilities on the page, Jeremiah “Terminator” LeRoy become the queer it lit boy of a generation.

When we think of documentaries about North Korea, it is usually with an eye toward illuminating what to this day remains cloaked in self-imposed mystery. As it has always been an excessively reclusive nation, this state of unknowing has been the primary trait most of the West associates with the DPRK. As a young country, that means most of its brief history is known only to itself, and even then there are probably only a few at the government’s upper echelons that are privy to details not disseminated to a populace fed on propaganda.

You won’t find out much about Louise Osmond if you look online. She is an Oxford history graduate who joined ITN as a news journalism trainee, and that’s all I or probably any other writer could know about her. But the personal details are irrelevant in the face of such a sturdy, and increasingly successful career as a documentary maker.

Despite frequently being labeled the most reclusive country in the world, in the past half decade or so there have been a preponderance of documentaries about North Korea. TV shows, websites and documentary filmmakers have all offered their own spin on what is colloquially referred to as “The Hermit Kingdom”. Though told in different ways, all of these pieces have generally come to the same conclusion:

By definition documentaries sound like a pretty straightforward genre; but the evolution of the genre over the years is anything but simple. While I don’t want to sound combative towards the artistic growth of any art form documentaries have splintered into so many different directions, we’re running out of terms for all of the varied sub genres. For every Michael Moore, Alex Gibney, or Errol Morris there seems to be only one Frederick Wiseman which is why his work always feels like a breath of fresh air.

In a time when facts, figures and certainties are thin on the ground, when reality itself appears to be fragmented into many non-congruent shards, it is perhaps not so surprising that some sense of perspective can be gained in the comforting darkness of the cinema theatre. Discombobulated by events both political and personal, I sought refuge from Manchester’s silvery anti-summer at a screening of Paul Fegan’s Where You’re Meant To Be, chronicling musician Aidan Moffat’s journey around Scotland in his quest to re-interpret some of the country’s folk standards in a more contemporary light. Throughout the film and the subsequent Q & A with Fegan and Moffat at Manchester’s Home, the theme of authenticity surfaced from the loch of uncertainty that clouds our ability to make sense of these times.

In the fifties, Tex Avery made a series of shorts for MGM collectively called “The World of Tomorrow” in which the animator imagined what wonders the kitchen appliances, automobiles and society of the future will offer. The cartoons present with one fantastical gadget after another, all quite utilitarian, but with tongue firmly planted in cheek. The message is clear, technology may be our salvation, but left in the hands of man there will always be something to muck up.

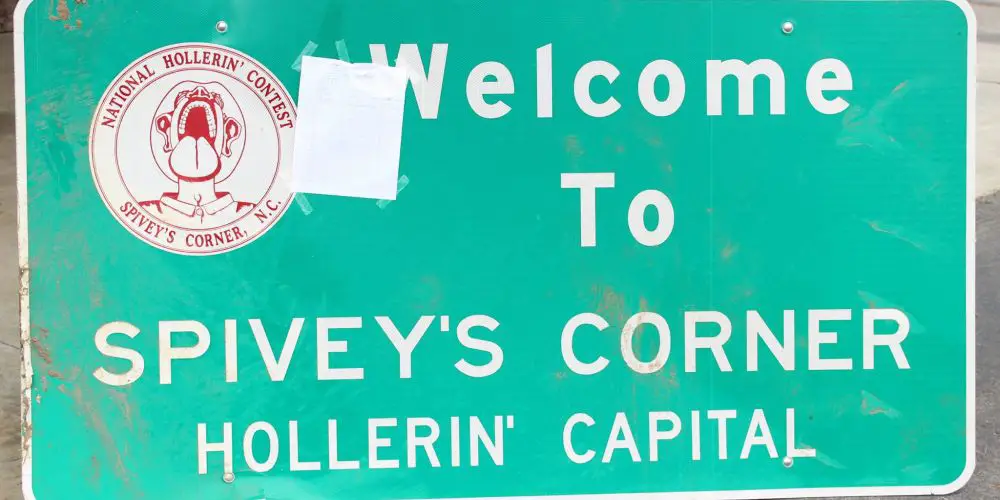

*Editorial Note: This documentary short won the Best Documentary prize at the first Drunken Film Fest, organised by Film Inquiry’s Jax Griffin. The documentary selections were hand picked by Arlin Golden, another contributor to the site* Every American community is home to countless strange pastimes and traditions, but many of these events don’t fully adapt to modern American life.

I was lucky enough to get the chance to interview The Hard Stop’s director, George Amponsah, producer, Dionne Walker and co-star Marcus Knox-Hooke, recently, before watching a screening of the film followed by an audience Q&A with Amponsah, Walker, Knox-Hooke and co-star Kurtis Henville. It was one of the most moving and insightful experiences I’ve had for a long time, and I’m still unravelling the many thoughts and feelings both the film and our conversation inspired. The IMDB description of the film The Hard Stop explains:

Jin Mo-young’s debut documentary feature, My Love, Don’t Cross That River, is extremely touching, and from solely watching the trailer of this South-Korean film, you can see why. Released for the festival circuit in 2014, Jin shows us a 98-year-old Jo Byeong-man and 89-year-old Kang Kye-yeol, who’d been married for 76 years. Jin filmed the elderly couple in their mountain village home in Hoengsong County, Gangwon Province for 15 months.