FILM, THE LIVING RECORD OF OUR MEMORY: A Film Preservation Manifesto

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

Did you know that approximately 80% of all the silent movies ever made are completely lost? Whether they rotted away, went up in flames, were melted down for silver, or were dumped in the ocean, so many movies created at the very dawn of the medium are likely gone forever. Those that we do have the pleasure and privilege of being able to watch today — some more than 125 years old! — only exist thanks to the efforts of individuals who have dedicated their lives to preserving our cinematic past. Inés Toharia Terán’s new documentary Film, the Living Record of Our Memory shines a spotlight on these individuals and serves as a rallying cry for the importance of film archiving and preservation in our modern, digital world.

Rotting Reels of Memories

Whether slapstick shorts or newsreels, industrial films or old home movies, moving images serve as a window into the past; they provide historical context that helps us better understand our present and prepare for our future. In watching documentary footage of concentration camps being liberated, we witness horrors that must be remembered so they cannot be repeated; in watching movies made outside of colonial influence in countries across Africa and Southeast Asia, we see evidence of vibrant cultural history that might otherwise have been wiped out by imperial powers. For these and so many other reasons, film preservation is critical — but it wasn’t always seen that way.

Film, the Living Record of Our Memory introduces us to some of the earliest archivists, people who believed that movies were not mere disposable entertainments but works of art worth preserving and revisiting in the years to come. In the early days, before film began to be truly taken seriously as an art form, this was an attitude that was not yet the norm; new movies are being created constantly, many reasoned, so why bother holding on to the old ones? (It pains me that some people probably still feel this way today.) But some felt differently, including Henri Langlois, a legendary cinephile and pioneer of film preservation who stored reels in his bathtub, saved F.W. Murnau’s Faust from being destroyed by the Nazis, and hosted screenings in Paris that were a major influence on the young filmmakers of the French New Wave.

The Power of Preservation

Langlois passed away many years ago, but many of his spiritual descendants—including silent film historian Kevin Brownlow and recently departed filmmaker Jonas Mekas — appear onscreen in Film, the Living Record of Our Memory to discuss the importance of film preservation and the many difficulties inherent in such work. As one person notes, the archival process, like the filmmaking process itself, is inherently collaborative; many people and their knowledge, resources, and time are necessary to save even just one film.

In addition, different places throughout the world present their own unique film preservation challenges, especially in the Global South. In countries with volatile political situations, cultural heritage is often destroyed as a means of consolidating power; in tropical climates, air conditioning is critical for preventing the deterioration of film reels — and sometimes, reliable electricity is not that easy to come by. Yet it’s so important to preserve the national cinema of these countries so that the canon can properly reflect the breadth of cultures that our world has to offer.

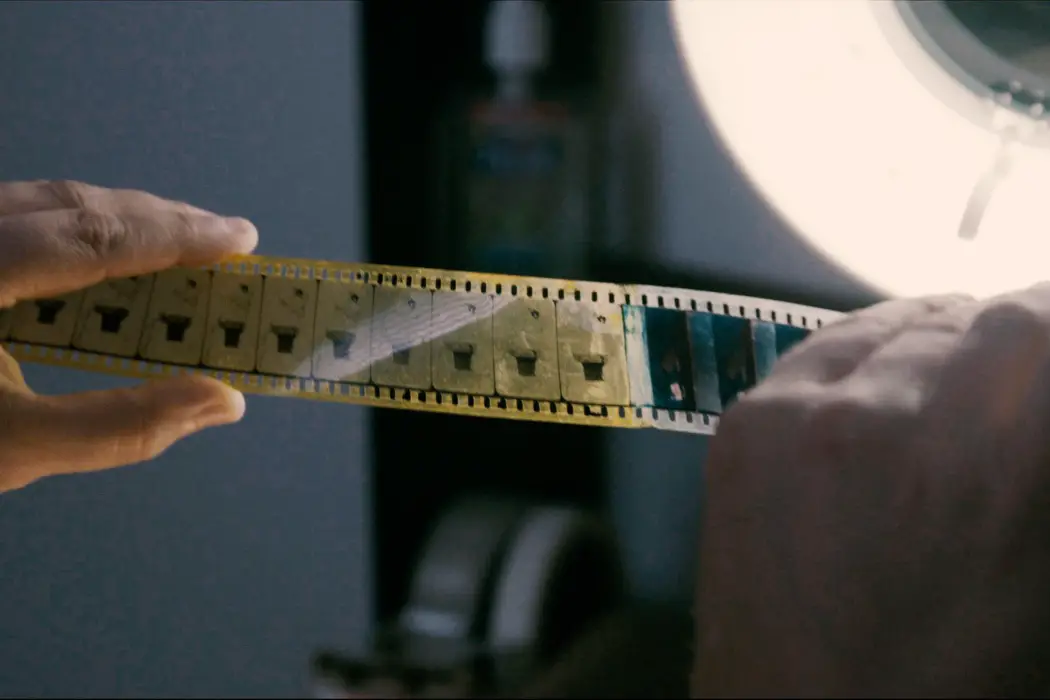

Film, the Living Record of Our Memory covers everything from the importance of saving old film equipment — including an amusing anecdote about director Ken Loach getting the old film editing tape he needed from Pixar, of all places — to the difficulties of identifying unmarked reels by visual cues such as monuments that appear in the background of shots or the typeface used on the title cards. We learn about the role of television in film preservation — studios were finally motivated to save their old movies when they realized they could make money selling them to television — and see how rot spreads through film reels like a cancer unless they’re stored properly. The film even delves into the latest technology being developed to store moving images, such as imprinting them on synthetic DNA!

It’s a lot of information packed into a two-hour running time, and given that it relies primarily on talking heads to convey it, Film, the Living Record of Our Memory can occasionally feel a bit dry. But if you’re as passionate about saving and watching old movies as I am, you’ll still find a lot to fascinate and inspire here. The parts I enjoyed most focused on the nitty-gritty technical work involved in restoring old movies to their former glory, from cleaning up scratches to re-tinting frames. In some cases, we get to see side-by-side footage of the before and after of a restored film, which really drives home the necessity of the work being done. After all, it’s one thing to hear various people tell you why restoring old films is important; it’s another thing altogether to see footage from one of the earliest adaptations of the 16th-century Chinese novel Journey to the West, shot in 1927.

Conclusion:

With the ubiquity of smartphones and the ability to upload videos to YouTube, it is easier than ever to make, distribute, and watch moving images — but that doesn’t mean we should neglect and forget all of those that came before. Film, the Living Record of Our Memory provides ample evidence as to why it is so important that we continue to remember, and to support those who make it possible for us to do so.

Film, the Living Record of Our Memory begins screening in theaters in the U.S. on February 27, 2023. You can find a list of upcoming screen dates here.

Watch Film, the Living Record of Our Memory

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. In addition to movies, she's also a big fan of soccer, BTS, and her two cats.