music

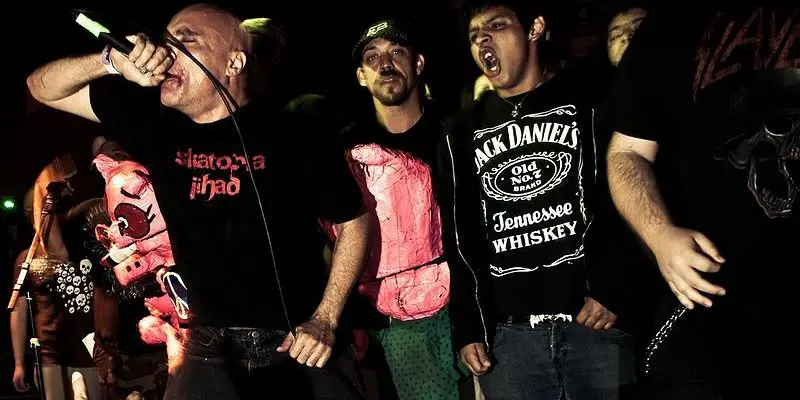

A while ago, I had the pleasure of speaking with one of the members of the legendary band Green Jelly, Matt Groopie. I had originally planned on speaking with Matt about the small Canadian tour that Green Jelly had taken in the beginning of May, but my plans changed quickly after experiencing what I considered to be one of the most entertaining live shows I had ever seen. That being said, I should make it clear that I’ve been to hundreds of shows and concerts.

It’s very easy for the media to get overexcited about a new Meryl Streep film, and one costarring Hugh Grant and directed by Stephen Frears at that, but this time there’s something different. I think maybe, what with the recent success of The Iron Lady and the confusion over Suffragette (where she was on screen for only a few moments), the media and filmgoers are suffering from a little overindulgence when it comes to one of the world’s greatest actresses. So although Florence Foster Jenkins has been promoted widely, it hasn’t been the film on everyone’s lips.

Director John Carney’s most beloved films are all about the idea of “authentic” music, with protagonists who are either singer-songwriters or bands all struggling to make a living when soulless pop is all that is keeping the music industry alive. His previous film Begin Again was about a struggling singer and a washed-up music producer making a concept album that laughed in the face of pop music’s obsession with inauthenticity. The characters were celebrated in the film, despite making an album of beige-sounding Starbucks music that seemed to ignore that rock’n’roll is so exciting because of its lack of authenticity.

In the beginning, there was light. It moved, it danced, it enthralled, but in the end, it was just light. Even in the silent era, exhibitors recognized the value of sound, coming up with a wide array of live and pre-recorded solutions to the problem of representing reality with only one of our five senses (and drained of color at that).

A subtle yet intriguing glimpse at family built on celebrity, One More Time spins a much darker story into a lighthearted drama. Indie earmarks set the tone of the film, as the dialogue-driven character study deftly navigates each family member’s individual flaws while also allowing for a lasting bond with the audience. Pepper in the oddball charm of its male star alongside a borderline Gen X female protagonist, and the foundation is set for a well-crafted, yet easy-on-the-emotions watch.

Since breaking out with Trainspotting 20 years ago, director Danny Boyle has proven himself to be one of the UK’s most diverse filmmakers. Growing up in Greater Manchester, UK, in a working class Irish Catholic family, Boyle spent eight years as a choir boy and intended to join the Priesthood, deciding against it at the age of 14. He went on to study English and Drama at Bangor University and began his career in theater in the 1980’s.

It’s not often that you can say that someone is one of your favourite directors, but for a long time you didn’t even know their name or recognise that all the films you liked were theirs. Jeanie Finlay is a special case though, the documentarian who pushes you hard to look at the subject and never at themselves. Through her good working relationship with the BBC I and many of you in the UK have been watching her films without ever actually joining the dots and seeing that Finlay was the filmmaker behind them all.

Between fronting various rock bands, starring in ’80s B-Movies and baring it all for dinner guests in the Aloha state, Jon Mikl Thor has been existing on the fringes of American pop culture going on 5 decades now. The subject of the new documentary I Am Thor, my review of which you can read here, he is poised to come roaring back onto the heavy metal scene and beyond. Jon was gracious enough to take the time to speak with me about the documentary, his career, and all that lays ahead.

Documentary filmmaking is an interesting thing: while an actor in a fiction film can (though certainly doesn’t necessarily) excise their own personal ego and inhabit a role entirely separate from themselves, the documentary subject does not have this luxury. In fact, for the subject of a documentary to be successful it takes precisely the opposite skill; to be fully present in oneself, perpetuating the most “you” version of you possible.

Composers are an underrated yet invaluable aspect to the world of cinema. They have the ability and duty to evoke various emotions in the audience, causing excitement, nerves, tears and goosebumps, sometimes all at once. It takes great skill to match the images on the screen to a suitable audio, and one man is notoriously known for his breathtaking soundtracks that complement filmmakers’ work and enhance the cinematic experience.

One of the hardest things to decide when reviewing a film is if the intentions behind the production feel genuine. One aspect that always arises during the Oscar/Award periods is actors doing roles or movies being made purely for “Oscar bait”. The idea of making a movie purely for the sake of gaining awards attention is somewhat cynical, but the transparency of movie production nowadays makes this something that sadly may have some truth behind it.

Closely approaching Quentin Tarantino’s new film The Hateful Eight arises expectations not only because of the name he has created for himself, but also because we are aware of the repeating pattern of collaborators in his films. But this piece is not about the cast of the film nor about Tarantino’s specific style. It is about the collaborators behind the scene, specifically on his first time collaboration with Ennio Morricone as a composer of the film’s original soundtrack.