HIGH NOON: Celebrating The Power Of Individual Fortitude

David is a film aficionado from Colchester, Connecticut. He enjoys…

In the midst of our current fear-controlled political environment, it’s common to turn to film for not only escape, but for an idealized direction. Many modern movies and TV shows have interlaced these societal fears into their narratives, becoming an allegory of our troubled times. Yet, looking backwards can sometimes be just as meaningful.

Hollywood has undergone shifts in perspective since the dawn of film. In the 1950s, the Cold War was at its peak; heads in the sand, the country feared the encroaching threat of the Soviets, not only from abroad with growing nuclear capabilities, but within our own walls. McCarthyism and the Hollywood Blacklist served to disturb the already frazzled mindsets of those in show business, making enemies out of previous friends due to these irrational fears. Often, people who were found to have connections to Communism were told to name names in exchange for leniency, leading to a world infused with paranoia and fear-laden cautiousness.

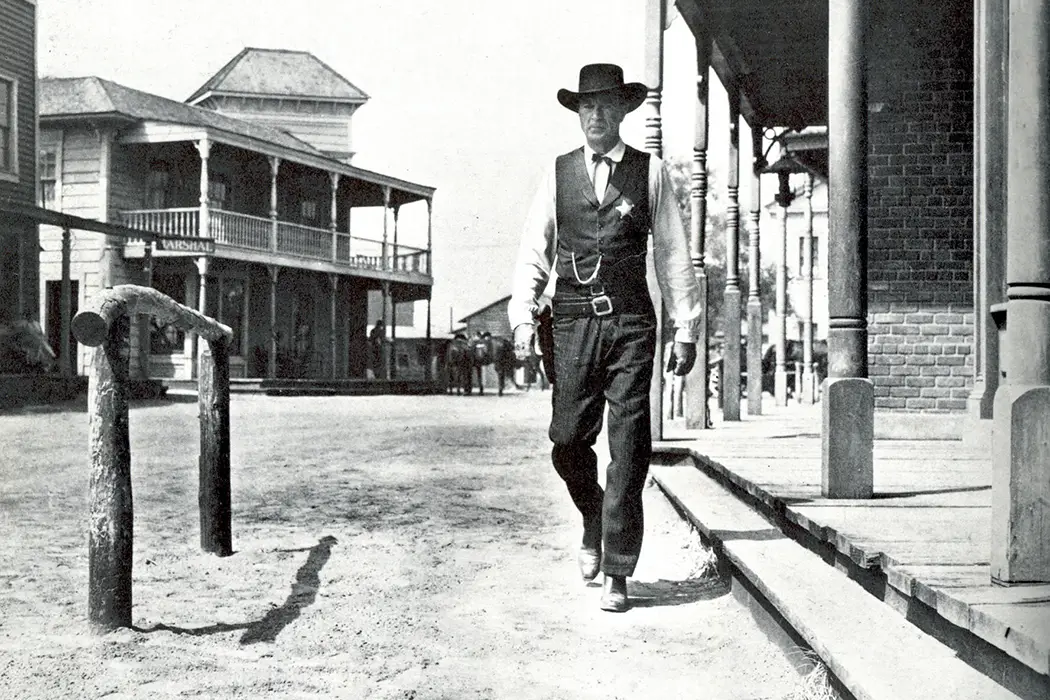

In the midst of all this came High Noon, premiering in 1952. The film, which was produced by Stanley Kramer and directed by Fred Zinnemann, focuses on a man named Will Kane, a marshal of a small New Mexico town that is suddenly presented with the threat of an old nemesis that had just been pardoned and released from jail. Coerced to leave town to save himself, Kane instead stands strong, despite the lax attitude of the townspeople around him that refuse to help. Though a clear allegory for the strength of the individual against the threat of the Hollywood Blacklist, the film is still just as relevant today. Like the second hand of the ticking clock that is often seen throughout the film, the cycle of fear and paranoia never stops; it simply circles back around time and time again.

Technical Proficiency

High Noon stars Gary Cooper as Will Kane. Once a prominent marshal of a small village in the New Mexico territory, he has just recently married the lovely Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly), a Quaker, and they are about to embark on a new life together managing a store in another town. Soon, though, news is brought to them that Frank Miller (Ian McDonald) has just been pardoned for the crime he was originally sentenced for, and is now coming on the 12:00 train, accompanied by three henchmen. Kane, who was responsible for catching Miller in the first place, is tempted to run, knowing that Miller wouldn’t be coming to their town for any reason but revenge.

After deciding not to leave, though, Kane glances at a nearby clock, and determines that he only has an hour and 20 minutes before Miller will be arriving. In order to stack the odds more in his favor, he attempts to round up a posse that will stand with him against Miller and his gang. The excuses for noncommittal are numerous, though, including: a young deputy who is bitter about not being chosen as the next marshal after Kane leaves, an older friend who claims he is past his gunfighting days and will only be a nuisance, a judge (who also sentenced Miller) who chooses certain life over potential death, people who would prefer not to upset their perfect town with a gunfight, a deputy who is at first willing, but later backs off once he realizes the odds, and more.

Ashamedly, the only ones who seem ready-minded to assist Kane are a man missing one eye and a 16-year-old boy. Kane, then, though still tempted to flee, stands his ground, taking on all 4 gun-wielding criminals single-handed.

With an hour and a half running time, yet with no action or gunfighting so typical to Westerns until the last few minutes, High Noon was at first a peculiar film for the time. From the moment Will Kane discovers that Frank Miller and gang are coming for him, until the actual fight, the film plays out in almost real time. Quick glances at clocks or pocket watches are frequent, counting down the minutes he has left. These moments build and escalate the tension that the characters are feeling, and in turn this tension extends beyond the screen to the viewer. As a result, the film is never disengaging, moving forward with momentum that is almost entirely based upon the thought of what is coming.

The cinematography and subject choice is also distinctive amongst Westerns. The Westerns of John Ford or Howard Hawks were known for their wide-screen panoramas and stark, colorful depictions of the Old West. Though many also took place in singular towns, they didn’t hesitate to show those towns in their entirety, with the sweeping vistas of the surrounding scenery standing out.

Here, though, the film is not only shot in black and white, removing the possibility of admiring the landscape colors, but also takes place almost solely within the expanses of a small town. As Will Kane travels from one building to the next, the film, rather than expanding outward, instead gets smaller, feeling more claustrophobic with each passing second. Frequent shots simply show a distraught Kane wandering through the town by himself, en route to the next place to ask for help. Significantly, once we finally do get a glimpse of the town in its entirety, it is almost exactly noon, when Frank Miller is about to emerge. Will Kane, in a wide-angled shot, is the sole speck of life in a ghost town, now that he has been completely abandoned by the cowardly townspeople.

A further noteworthy aspect of High Noon is its soundtrack, which though containing a score, is most remarkable when playing one song on repeat: “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darling”, composed by Dmitri Tiomkin with lyrics by Ned Washington. The song, which flits between Tex Ritter‘s deep-voiced country singing and an instrumental version, is a recurring leitmotif throughout the film, often played as Will Kane walks through the town. As opposed to feeling overplayed, though, the repetition is yet another constant reminder of the impending danger. The lyrics themselves even allude to this, with lines such as: “I do not know what fate awaits me/I only know I must be brave/And I must face a man who hates me/Or lie a coward, a craven coward/Or lie a coward in my grave.”

Individual Strength and Character

High Noon is, above all, illustrative of the strength of individual will, a theme common to director Fred Zinnemann‘s work. In A Man For All Seasons, for example, the character of Sir Thomas More stands strong to his claim that the King’s marriage is illegitimate, due to a divorce that would be against Christian beliefs; and it is a stance that costs him his life.

Here, Will Kane discusses his plight and asks for help at various places, including a tavern and a church, yet he is continually told to run instead, even up until the last second. Kane soon realizes that he is being told to leave town due to cowardice as opposed to concern, as his so-called friends would prefer not to take up arms alongside him despite Kane’s continued efforts to make their town safe. He is unwavering all the same, knowing not only that he is in the right but that, if he runs now, he will always be running.

It is perhaps this attitude and determinate will that makes this Gary Cooper‘s finest performance. Known for his soft-spoken yet tenacious personas, he triumphed through the years in roles similar to this one. But nowhere before or after did he truly capture such a range of human emotions from the beginning of the film to the end. From the moment he put his foot down, declaring that he wasn’t going to run from Frank Miller (even at the expense of disrupting his marriage to Amy Fowler), until he finally steps out onto that lonesome deserted street, Cooper’s Kane ranges from foolish naivety, to passively quiet, to reluctant acceptance, and finally emerging a triumphant hero.

The closeups of Cooper’s fiercely steadfast expression as he steps out to his fate, or, afterwards, his utter disdain for the townspeople who now swarm around him after the fight is over, are snapshots of what all great actors should aspire to.

Supporting Roles

In addition to Will Kane, the film focuses a great deal on the strength of its supporting characters, which includes his wife Amy Fowler, played by Grace Kelly. As a Quaker, Amy doesn’t initially believe in Will’s choice to stay and fight, and her pacifist views create a rift between them; however, her ultimate act at the end of the gunfight is one directly against this. She chooses her husband, knowing that she would prefer to live with somebody she loves rather than abide by her personal views. Violence is not necessarily the answer, but when faced with no other choice, High Noon states that it is best to fight for what is right.

The idea of Kane staying being an act of heroism, though, is one that is contrasted with Helen Ramirez (Katy Jurado), a Mexican woman who is married to Harvey Pell (Lloyd Bridges), the former deputy of Kane who refuses to help fight Frank Miller. Ramirez not only has ties to Kane, a former lover, but also to Miller, and as a result she chooses to leave on the next train rather than wait for the consequences of his return.

Her decision to leave, though, rather than being cowardice as it would have been for Kane, is instead seen as an alternate form of courage; here in town, she has created a comfortable life for herself, which as a Mexican woman for the times is a rare and commendable feat. In leaving the town and knowing that she will have to start over elsewhere, she shows strength of will in a comparable way to Kane. The two are often juxtaposed throughout the film in order to show this, with scenes alternating between Kane’s wanderings around town and Ramirez packing up and making amends before leaving.

Relevance to the Times and to Now

Will Kane is the rare individual that stood up against the forces that stacked against him, despite his lack of backing and support for doing so. He is the epitome of moral strength and fiber, and for that reason he is allegorical to the times, representing those rare individuals who either exercised their freedom to align themselves with the Communist Party, or refused to name names once they were accused of being a member.

Looking even further than the times, though, Will Kane could be seen as an archetype for the strong-willed individual that we should all aspire to be, and indeed, that many famous leaders have idolized through the years. High Noon was known as a favorite amongst US presidents, including Bill Clinton, who showcased the film a total of 17 times at the White House during his presidency. Kane is the aspiration for what a leader should be – whose very job is to stand up for what is right, regardless of outside opposition.

Our last president Barack Obama could be seen as a representation of Kane’s ideals, with a strong determination to stand up for what he felt was right despite the lack of support from others (ahem, Congress). Yet now, Donald Trump ran a campaign based on xenophobia and a general fear of an “other”, an aspect very reflective of the societal fears in the 1950s. As we have seen within the past few weeks, his agenda concerns preventing people from coming into this country that are not stereotypical “Americans” i.e. immigrants, Muslims, Mexicans; basically anyone who previously would have been welcomed with open arms but is now being scapegoated for political purposes.

We should all attempt to dissuade this culture of fear, though, and aspire for the ideals represented in High Noon. Stand strong against the forces that attempt to control us, even if doing so is not the popular thing to do. Stand against bigotry, racism, and fear in general. You can already tell that this is an ideal shared by many, seen in the protests that have erupted since the onslaught of our president’s implemented practices. But we can make a difference in our own individual ways as well, by simply refusing to be quiet when we see something so blatantly wrong occurring around us.

Further, know when it is best to take the fight or flight approach, as represented by both Will Kane and Helen Ramirez, respectively. There are times when fighting opposition would do more harm than good, and walking away is in reality the stronger decision to make. It is by using these examples, at our own discretion, of course, that we can fully know what is the right decision at any given moment.

Conclusion

It shouldn’t be too surprising that a film which emerged during the Cold War is now more relevant than ever. As mentioned, societal fears are a constantly rotating wheel, and Hollywood has always been allegorical of them. High Noon was reflective of the heightened fear of the Soviets in the ’50s, fears which are now similar to the xenophobia that has been raised and further inflamed by our political leaders.

High Noon is a timeless historical remnant of what it means to stand strong against opposing forces, regardless of how much easier it would be to take the easy way out. We should all aspire to be Will Kane, and to watch this movie as a reminder of the sheer strength of individual will. He’s the hero we need right now.

What are some of your favorite films that reflect societal fears? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

David is a film aficionado from Colchester, Connecticut. He enjoys writing, reading, analyzing, and of course, watching movies. His favorite genres are westerns, crime dramas, horror, and sci-fis. He also enjoys binge-watching TV shows on Netflix.