drama

Growing up as a first generation Asian American, I looked to television and cinema for hints to “fit in” with all the other Americans, to improve my grammar and English, to embrace the idea of being American. In that transition, I severed some of my Filipino roots. I can understand Tagalog, but I can’t speak it.

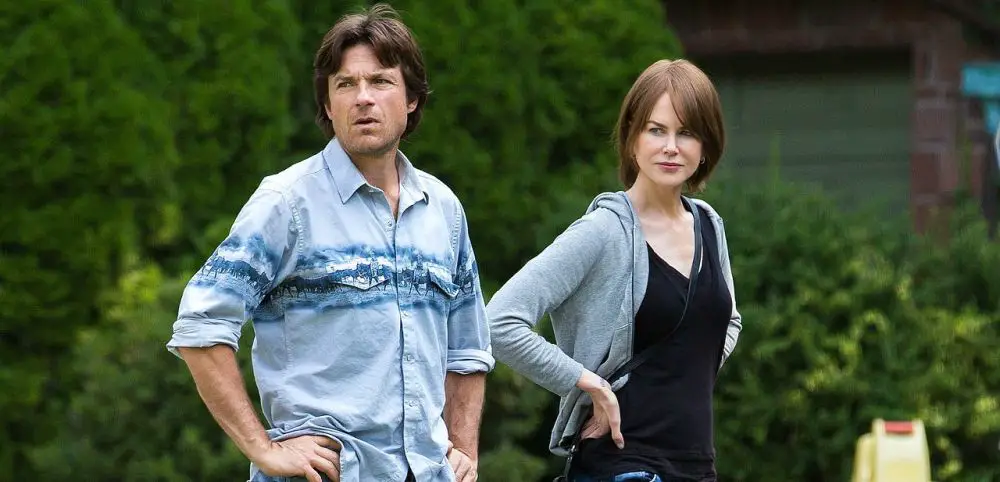

Despite the title being one of the most fascinating I’ve seen in a while, Careful What You Wish For, directed by Elizabeth Allen Rosenbaum, is about as painfully average as a neo-noir thriller film can get. You will not be surprised or fascinated at any point in this film, where a younger man takes an older woman (Isabel Lucas) as his lover. Though, said older woman isn’t all that much older than him, sadly showing how limited roles for women are in this industry.

While many recent horror films have been heavily influenced by the works of prominent directors of the 1980s like David Lynch, John Carpenter and David Cronenberg (very good ones like The Guest and It Follows), this one addresses subject matter not even those films were willing to tackle. Richard Powell’s Heir is the next great homage to those great directors, and can proudly be a part of the recent resurgence in thoughtful horror films designed more to represent real world conflicts as opposed to cheap scares. The plot is simple at first:

In Matthew Solomon’s Chatter, Agent Martin Takagi (Tohoru Masamune) comes across the intimate video chats of married couple while monitoring Internet traffic for the Department of Homeland Security. The married couple, played by Brady Smith and Sarena Khan, begin to discover that their new home is haunted. In the same vein of horror films such as Paranormal Activity and the more recent Unfriended, the mechanics within this film felt familiar.

Whit Stillman’s adaption of Jane Austen’s relatively unknown novella, Lady Susan, follows the delightfully scandalous exploits of the recently widowed Lady Susan Vernon (Kate Beckinsale). Lady Susan is forced to leave the Manwaring family’s estate in the midst of adulterous allegations, instead taking up residence with her in-laws and their handsome young relative, Reginald DeCourcy (Xavier Samuel), whereby she attempts to marry off her long-suffering daughter and elevate her own social standing in the process. The ensuing events make for one of the most entertaining and joyfully witty Austen adaptations we have yet been treated to on screen.

In Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, a treatise about the human condition, he wrote, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” For many people the work they do is pointless, only going far enough to provide limited sustenance while killing the spirit inside which yearns to be free. Naturally, this is nothing new.

It’s very easy for the media to get overexcited about a new Meryl Streep film, and one costarring Hugh Grant and directed by Stephen Frears at that, but this time there’s something different. I think maybe, what with the recent success of The Iron Lady and the confusion over Suffragette (where she was on screen for only a few moments), the media and filmgoers are suffering from a little overindulgence when it comes to one of the world’s greatest actresses. So although Florence Foster Jenkins has been promoted widely, it hasn’t been the film on everyone’s lips.

Every year, we get countless reports that there isn’t enough diversity in Hollywood storytelling. In the past couple of weeks alone, GLAAD’s annual media report has shown that LGBT diversity is only visible in TV, whilst Asian-American actors have begun a protest website called “Starring John Cho”, to highlight the lack of leading roles given to people of their ethnicity. A story that needs to be told There was a line in GLAAD’s celebration of diversity in independent cinema that rung alarmingly true, as they highlighted that diverse audiences shouldn’t have to look to the arthouses for films that relate to them.

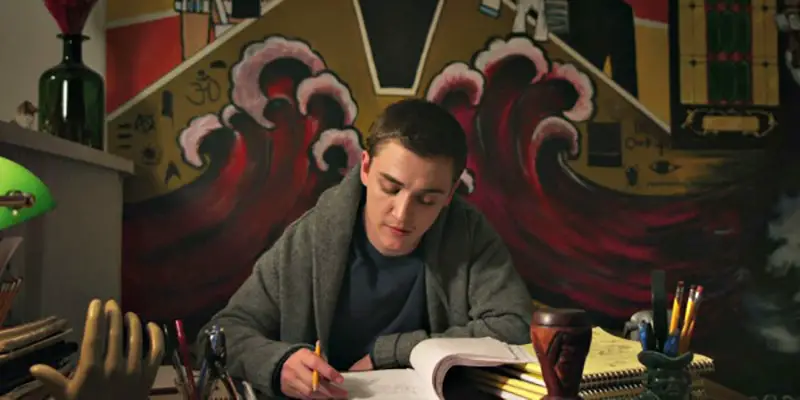

Director John Carney’s most beloved films are all about the idea of “authentic” music, with protagonists who are either singer-songwriters or bands all struggling to make a living when soulless pop is all that is keeping the music industry alive. His previous film Begin Again was about a struggling singer and a washed-up music producer making a concept album that laughed in the face of pop music’s obsession with inauthenticity. The characters were celebrated in the film, despite making an album of beige-sounding Starbucks music that seemed to ignore that rock’n’roll is so exciting because of its lack of authenticity.