horror

Film is one of the best artistic mediums because it’s always growing; it speaks every language, and every place in the world has their iteration as to what’s scary, twisted, weird or just downright bizarre. Different countries offer different interpretations of horror, from China where vampires hop to Korean Shaman. They don’t wave crosses, nor do they compel the power of Christ upon anyone, but just don’t fall in love with Isabelle Adjani.

Is this any way to sell a board game? Hasbro’s perennial moneymaker “Ouija” is the basis of Universal’s micro-budget horror franchise in the making, and it’s hard to imagine a game manufacturer working any harder to discourage people from buying its product. The 2014 release Ouija opened at number one, and a followup was inevitable.

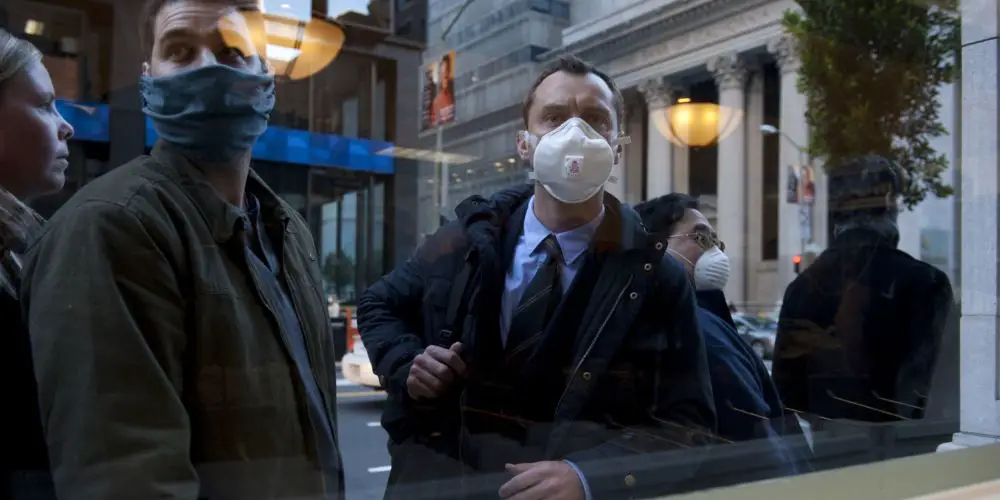

When we think about viruses in cinema, we usually think about them in conjunction with turning us into the undead. Indeed, the stunning alacrity and volume at which Hollywood churns out zombie epidemic films begs us to wonder if we have truly exhausted the “what if?” nature of this particular vein of horror.

Horror is in an extremely interesting place at the moment. Thanks to the rise of video-on-demand platforms and new technology, barriers between creator and distributor are disappearing, the amount of independently-made films are rising and the availability of these films is quite accessible. The trade-off of this is the problem of quantity over quality, which has meant that, much like the exploitation era of filmmaking in the 1970’s, every new or original film that is successful is followed with a string of derivative imitators, looking to cash in on genre recognition or fans looking to branch out on that particular subject matter.

Anthology films are generally regarded as being uneven, and even ones that are respected are sometimes not perfect through every single segment. I wanted to explore anthology films by looking at some with mostly negative reviews, hoping to find something great hidden within. Some of the films I watched in preparation were bad, with no moments of relief to help make it through their running times, while others were enjoyable with slight problems.

Nineties psychological horror The Blair Witch Project wasn’t an instant hit. Though a triumph with critics, its box office success was slow, but it now stands as one of the most financially successful independent films of all time, and as a forefather of the found footage trend. Not only did The Blair Witch Project pave the way for found footage horrors like [Rec], V/H/S, and the Paranormal Activity series, sci-fis and fantasies like Cloverfield, Trollhunter and Chronicle also used the format.

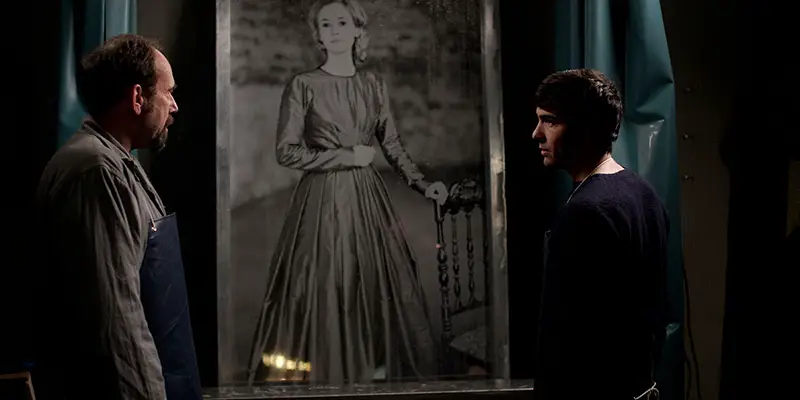

When the title card appears in Daguerrotype, it announces the film as “Le secret de le chambre noire”. That title reflects the film’s goals as a dark, foreboding ghost mystery, and it probably does so better than the title “Daguerrotype” does. But what I like about the title Daguerrotype (misspelled though it might be), is that it refers to the most interesting part of the film:

The idea of the “secret sequel” seems to be a new marketing scheme in horror cinema as of late. Earlier this year, a sequel to the film Cloverfield came out, called 10 Cloverfield Lane, yet nobody knew it was a sequel until a couple months before its premiere. In similar fashion, Blair Witch, the sequel to 1999’s seminal horror The Blair Witch Project, was originally filmed under the fake title “The Woods” so as to hide its true intentions.