horror

Written and directed by Jon Watts with co-writer Christopher Ford back in 2014, Clown has been in the offing for some time now. Originally conceived in 2010 as a fake trailer for a forthcoming feature attraction fictively produced by contemporary horror genre guru Eli Roth, Watts’ first feature length production is a mixed bag. Blending various elements of body horror with the basic thematic structure of a domestic comedy, Clown is more silly than it is scary.

The title of horror anthology Southbound implies a deep sojourn into racist, redneck Americana, locked and loaded under a blood red, lone star. This is a Democrat’s version of hell, ruled by Donald Trump’s tentacles and all of his Republican demons, suckered into building a never ending wall between America and the rest of the world. Southbound suggests a one-way ticket to Hades, but its various characters are still on their terrifying journeys, clutching desperately to their ever diminishing morality.

You may not know her by name, but you’ve definitely seen her face and are familiar with her work. She’s been on your small screen and silver screen starring along side Angelina Jolie, Christina Ricci, Zachary Quinto, and Natasha Lyonne to name a few. She may not look as glamorous as your traditional Hollywood starlet and she doesn’t often play the leading role, but Clea DuVall’s natural beauty and talent first grabbed my attention about fifteen years ago on a day I vividly remember.

Lights Out initially seemed to be promising. Though reminiscent of other horrors I have seen, the idea of a creature that only lives in the dark is still an interesting and potentially frightening subject; that is, if it’s composed with the right balance in both story and direction. Unfortunately, like many dime-a-dozen horror films, Lights Out suffers from an all-in approach, choosing to simply attempt to scare the viewer by any means necessary rather than working on making it genuine.

Nearly everything about the film The Shallows seems to indicate that you wouldn’t be at a loss for missing it in theaters. The premise of an attractive woman in turmoil, coupled with an unbelievably vicious shark – each of these stories on their own has been done time and time again. Yet, somehow, The Shallows manages to just surpass the murky depths that most of those films sink to.

There is offense to be taken with the frame and exterior of physical bodies. Beauty, it has been said, is in the eye of the beholder. Yet, one can’t help but feel that, since the rise of feminism and the development of the male-gaze interpretation, almost all appreciation for the aesthetics of a given film has been entirely lost.

After a brief hiatus with Fast and Furious 7, mainstream horror’s prodigal son James Wan has returned to the Devil’s Church of Jump Scares with a sequel to his paranormal blockbuster, The Conjuring. The main lesson he seems to have learned on his franchise-hopping action excursion is how to make things feel absolutely massive, and in following the golden rule of sequels, he’s applied that bigger-is-better ethos to The Conjuring 2. The ghostbusting duo of the first film – Ed and Lorraine Warren – are called to London to flush out some more housebound demons, but in an effort to raise the stakes over the first film, Lorraine is also faced with her own adversaries:

German expressionism was an art movement that began life around 1910 emerging in architecture, theatre and art. Expressionism art typically presented the world from a subjected view and thus attempted to show a distorted view of this world to evoke a mood or idea. The emotional meaning of the object is what mattered to the artist and not the physical reality.

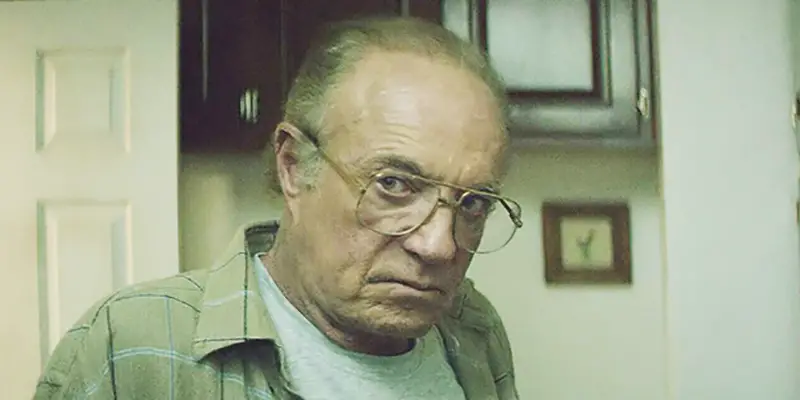

While many recent horror films have been heavily influenced by the works of prominent directors of the 1980s like David Lynch, John Carpenter and David Cronenberg (very good ones like The Guest and It Follows), this one addresses subject matter not even those films were willing to tackle. Richard Powell’s Heir is the next great homage to those great directors, and can proudly be a part of the recent resurgence in thoughtful horror films designed more to represent real world conflicts as opposed to cheap scares. The plot is simple at first:

Set in 1630, Robert Eggers’ The Witch follows a family banished from a Puritan community and forced to live, isolated and penniless, in a remote woodlands shack. Soon, malevolent forces begin to molest the kids and infect the goat, and the family is engulfed in a maelstrom of religious hysteria and occultist magic. With its deeply unsettling atmosphere and frenzied performances, The Witch has (not undeservedly) become one of the most acclaimed horror films of the new millennium, with many critics praising its attention to detail and the slow-burning tension of its narrative (as well as its mascot: